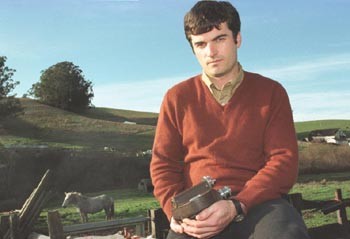

Blast from the past: Sonoma County filmmaker Abe Levy cradles the antique camera he used as a student. These days, Levy employs state-of-the-art digital technology to make his films.

Reel Deal

Local filmmakers shoot for the big time

By Daedalus Howell

“WE’RE READY for your close-up, Mr. Howell,” says Tomales-bred filmmaker Abe Levy, exhaling a plume of Parliament cigarette smoke into the cab of a rented moving truck. Inside, I’ve been incubating a hangover while the truck’s stick shift massages my spleen. It’s 7 a.m., and we’re parked near a jagged precipice in Angeles National Forest, about an hour’s ride from the movie-mad bustle of Southern California, or as Levy likes to say, Lo-Cal.

The arid park has loaned its Martian terrain to innumerable episodes of Star Trek, but on this muggy summer’s day in 1998, it’s standing in for a hillside in San Francisco, circa World War II. My old chum Levy is assistant director on director Scott King’s noir-esque cryptology thriller Treasure Island, which would go on to garner the Special Jury Award for Distinctive Vision at last year’s Sundance Film Festival.

Thanks to my pal, on this day I’m a bit-part actor–one of a couple of beat cops with nary a line between us, strapped into a vintage policeman’s uniform so uncomfortable that on the label below “Dry Clean Only” it says “M. de Sade” in Sharpie pen.

Two merciful takes later and I’m on a commuter flight back to SFO and a shuttle to Sonoma County. Levy, too, will eventually return to the county where he and a handful of other local filmmakers toil to bring their creative visions to the silver screen.

In the wake of the phenomenal success of last year’s The Blair Witch Project, independent filmmakers have more reason than ever to think big. But for every such runaway success story, there are hundreds of would-be directors struggling even to get their visions onto film, let alone into movie theaters.

Last September saw a sneak preview of Levy’s first feature, Max, 13, at Petaluma’s Phoenix Theatre. The film, a pastoral coming-of-age story about a teenage knock-about during the fateful summer before his first year of high school, was shot throughout Sonoma and Marin counties and seems to herald a new era in local filmmaking–locally grown, locally shown.

Though the 27-year-old Levy and his fellow Sonoma County filmmakers harbor loftier ambitions than local screenings, the fact remains that for most of them home is where the art is.

“I’m more akin to the artist next door to you painting landscapes than I am to a Hollywood director,” says Levy. “But it’s amazingly difficult to make films. Everything is against you, from the sun on down.”

Shot on Super 16mm film (a comparatively inexpensive wide-screen format popularized by director Mike Figgis’ Leaving Las Vegas) with a privately raised budget under $100,000, Max, 13′s principal photography was completed two years ago. The film then went through a grueling post-production period in which it was edited and scored before finally being previewed.

Mitch Altieri and Phil Flores, the duo behind Petaluma’s American White Horse Pictures, know that grind all too well. They’re in the midst of editing their first feature film, Longcut–a “ranch picture” chronicling the emotional journey of an 8-year-old girl left psychologically threadbare and mute after witnessing a brutal murder.

“Filmmaking is the ultimate challenge. It’s the worst, most horrible thing you can do to yourself,” says Flores. “It’s an endurance test.”

His partner Altieri concurs.

“It’s like self-mutilation,” Altieri says, and then wryly adds, “You’re a loser, a bum, and you have no money, but you insist on doing it.”

Camera Comrades

Alleviating some of the directors’ struggle is the support Sonoma County filmmakers offer by assisting on one another’s projects–a process many find mutually beneficial.

“I think it’s really important to work on other people’s films as well as one’s own. You really learn what and how other people are doing, which can help you in your own work,” says Levy, who has worked with most other local directors in an array of capacities, from director of photography to sound engineer.

Partners Altieri and Flores began their work as a film community of two in South San Francisco, but they happily expanded their contacts once they arrived in Sonoma County.

“Since the film industry is such a monster, it’s great to start off holding somebody’s hand,” Altieri says.

“Working with or without a partner is about the same as being an only child vs. having siblings–I’d imagine the pros and cons are the same,” Flores adds. “With a sibling, there’s someone who’s always there; you get their hand-me-downs and plenty of advice–but they’ll also put shit in your hair and plug your nose while you’re sleeping.”

Lee Cummings, a relative newcomer to the local scene (his upcoming short Imprint details a woman’s existential crisis while locked in a cell 15,000 feet underground), has enjoyed the local film community’s open embrace.

“I think it’s a lot better here than in Los Angeles,” says the 28-year-old Cummings. “I’ve been blessed to be surrounded by some amazing people. These filmmakers have been some of the most generous and outstanding people a person could be gifted to be with.”

“These guys don’t know the word stingy,” he continues. “They believe that success is built with an open hand and not a quick tongue behind someone’s back. Your success is theirs. Someone is going to make it, and we’re all riding coattails.”

Indeed, if local directors had a common ethos, it might read something like the Three Musketeers’ credo “All for one and one for all.”

“There’s no doubt that if any one of us got a gig we’d hire everyone else to be part of it,” Altieri says. “You kind of generate a miniature gang–like a Sonoma County film gang.”

Screen saver: Occidental filmmaker Max Reid cuts costs on his films by employing digital technology and computer editing.

Remote Control

Though e-mail, fax machines, Federal Express, and commuter flights help connect local filmmakers to the film industry at large, the fact remains that the art form is firmly based in Hollywood.

Veteran filmmaker Max Reid–who has made numerous films for television with such actors as Malcolm McDowell, Jason Priestly, and Kathleen Quinlan–doesn’t regret his move to Occidental from Los Angeles, though he admits that shooting in Sonoma County has its difficulties.

“You have to confront things that you normally wouldn’t have to confront. It’s a different environment,” says Reid, 55. “The advantages are basically that everyone is really open and you can work here with a lot more freedom than you can in Southern California. On the other hand, you have more difficulty finding people that are trained and experienced.”

Argentinean filmmaker Gustavo Mosquera R moved to Santa Rosa to be with his new family shortly after Moebius, his inventive foray into science fiction and political allegory set in the Buenos Aires subway system, swept up honors and critical acclaim internationally in 1997.

The move, however, has not been without its drawbacks.

“When working in Sonoma County rather than Argentina, I lose some things and gain others,” Mosquera says. “Basically, I lose all my connections with people in the industry, producers and the media in Argentina.”

The 40-year-old director–who is currently auditioning top-bill stars for a crime thriller he will direct for Hong Kong action maven John Woo’s production company–says the move has left him feeling a bit isolated.

“The first sensation is that you are away from everywhere–the most difficult thing is not being far from the nebula of Hollywood but being so far from all my old friends who helped me with my other films,” he says. “What I really like about being here, however, and being isolated in the hills, is the sense of a sort of paradise where I think much better and more long term about projects. I feel like I have more time to develop my ideas. This is my creative oasis.”

Indeed, many local directors, including Occidental’s Brian Smith, work in the county specifically for its rural charm.

“It’s the aesthetic. I especially love western Sonoma County,” says Smith, who is now in pre-production for his third feature, Dixie Blue Summer, a drama about a young woman dying of a brain tumor in a small Sonoma County town. “I’ve lived and worked here for six or seven years now, and have no interest or desire to move anywhere else.”

DV or Not DV?

A recent boon to independent and low-budget filmmakers is the advent of a new breed of digital video technology that allows for superior image quality and ease of interface with desktop editing systems that run on home computers. And it’s cheap–very cheap.

Consider that 40 minutes of digital videotape costs about $14. With processing, the same amount of Super 16mm film prices out at about $1,200 and 35mm film about $2,500. To transfer a 90-minute digital video feature to film print so it could show in theaters, however, runs the bill up to a daunting $50,000–a cost most independent DV filmmakers hope to defray by inking a distribution deal.

Levy joined the ranks of directors Spike Lee and Harmony Korine (director of the cult hit Gummo) last fall when he too began shooting his latest feature in the new medium.

It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Trying (the working title is inspired by the Bob Dylan song “It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding”) is about a 27 year-old emotionally retarded man who falls in love with a 15-year-old girl who is his intellectual and emotional superior.

Though Levy had scripted the film, the ease and low cost of digital video allowed his actors to improvise for long spates of time, something that would otherwise have been cost-prohibitive.

In a similar vein, Santa Rosa theater impresario Robert Pickett’s first film venture, A Divine Madness (a philosophical portrait of a community theater ensemble in the midst of a production of Anton Chekov’s The Cherry Orchard), probably would not have been possible without the inexpensive new technology.

Reid also changed his filmmaking M.O. to the digital format.

“It’s the only way to go unless your great aunt dies and leaves you $30 million,” Reid says with a laugh. “It cuts out a lot of the physical costs of feature filmmaking. My biggest cost on this last film was catering–more than half the budget, in fact.

“The real problem these days is coming up with a really good story,” says Reid, whose current project is a romantic comedy about a boy-genius time-traveler from the future who falls in love with 21st-century girl and is inspired by her ailing mother to clean up the environment.

“You can shoot a film for pennies and then it’s done,” says Reid. “Anyone can make a movie now. Digital video strips you down to basics–there aren’t any excuses anymore for not making a movie. I lot of people would say, ‘Oh, I can’t afford it,’ but the truth is you can afford it. You just have to confront the true obstacles of making a film, which is that one needs to be a real, competent artist.”

Indeed, the directors agree that ultimately it’s a film’s story that matters, not its production medium.

“What’s important is matching the story with the medium,” Mosquera says. “With The Blair Witch Project, for example, exposing the failures of the image was used to say, ‘This was made by three [people] in the forest.’ But I cannot imagine shooting Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon in digital video, for example. . . . As a director, it’s the story that should make you feel passion for the film.”

That passion, however, has to sustain the filmmakers through not only the laborious pre-production and post-production process but also the tedious, often humiliating self-marketing directors must endure when attempting to secure a deal.

Though a plethora of markets exist for independent filmmakers (including traditional theatrical distribution, cable television, video, or even the Internet), none are a sure bet, and competition is fierce.

Levy has just begun sending out tapes of Max, 13 to film festivals around the country. But he has no illusions about the odds of success. Getting accepted by festivals is tough enough when a director has a finished film, and even worse when he or she can offer only a rough cut.

“You hope for serendipity,” Levy says. “You hope that your film will be timely in some way that you didn’t expect, or that some influential person will say, ‘Hey, this is a good film.’ You have to be in the right place at the right time with the right film.”

Local Screening

Meet a local filmmaker and explore the growing connections between two of the world’s great religions on Friday and Saturday, Jan. 28 and 29, when the Sonoma Film Institute screens Jews and Buddhism: Belief Amended, Faith Revealed, a documentary co-directed by veteran Petaluma filmmaker Bill Chayes.

Some 30 percent of non-Asian-American Buddhists are Jews, and the two religions have developed a remarkable influence over each other’s practices in the United States. Chayes’ documentary, which is narrated by actress Sharon Stone, examines this phenomenon by combining interviews of believers with footage of dialogues between the Dalai Lama and Jewish scholars. Also included is archival footage of a televised encounter between David Ben Gurion and U Nu of Burma.

Chayes introduces Jews and Buddhism at 7 p.m. both days. The film will be followed by the documentary Delta Jews at 7:50 at the Darwin Theatre, Sonoma State University, 1801 E. Cotati Ave., Rohnert Park. Admission is $4. For details, call 664-2606.

From the January 27-February 2, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.