Gimme Shelter

Amid a boom in local population and jobs, Sonoma County is riding a go-go real estate market. Yet many remain locked out of home ownership.Do elected officials have the political will to address the need for affordable housing?

By Janet Wells

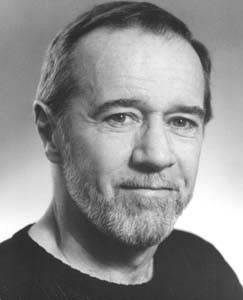

ARNOLD STERNBERG makes no bones about it–Sonoma County is in the midst of a housing crisis. And, in his view, the blame lies squarely on local government. “There’s a total lack of affordable housing and an unwillingness of local government officials to really face up to the problem and solve it,” says Sternberg, a 74-year-old attorney and former director of the non-profit Santa Rosa-based Bur-bank Housing Development Corp.

Sternberg’s gravelly voice tremor doesn’t hide his disgust for the housing situation, or the passion he puts into focusing attention on the lack of affordable housing.

In the mid-1970s, Sternberg served as then-Gov. Jerry Brown’s state director for housing and community development. Locally, Sternberg worked with Burbank Housing for 10 years, before moving to Fort Bragg two years ago. After more than 40 years in public service, he remains active behind the scenes as a housing advocate.

Sternberg places the responsibility for the housing crisis, not on the booming demand for wine country living, but on the lack of political backbone among elected officials.

Do the Numbers: Stats on Sonoma County housing prices.

A Success Story:Petaluma takes affordable housing seriously.

Searching South: Local movers and shakers turn to Silicon Valley for housing tips.

“First, they’ve got to make more land for high-density housing available,” he says of local and county officials. “Second, they have got to face up to the NIMBY [not in my backyard] problem and not cave in in the face of that kind of opposition.”

Anyone who has looked recently to rent, buy, or–even worse, find–subsidized housing in Sonoma County feels the pinch. These are teachers, janitors, lab technicians, students, cops, nurses, bank tellers. They earn decent wages, but not enough to pay for what has become the indecent cost of housing in the Bay Area.

By the numbers, Sonoma County’s housing situation looks grim–especially for those standing on the outside looking in. Countywide, home prices have ballooned an astounding 20 percent in one year. Rents are up, and vacancies hover in the 2 percent range–and even lower in Petaluma. A 5 percent vacancy rate is considered economically healthy.

The subsidized-housing situation is even more perilous. When the county opened its waiting list for the rental assistance program in March, 5,020 low-income households signed up in six weeks. Since then, only 600 families have found subsidized housing.

To further dampen the prognosis, Sonoma County must contend with multiple issues–population growth, agricultural preservation, gridlocked traffic, the high-tech boom, unfavorable local politics.

JUST BUILD more housing. Sounds simple. After all, there is a construction boom underway in the county, with new homes going up in almost every city. But most of those homes–“starter castles” with thousands of square feet, large yards, and garages–are far from affordable. For developers, it’s kind of a no-brainer. The more expensive the house, the bigger the profit. Local planning commissions and city councils give developers a boost by continuing to hand out permits for pricey single-family housing developments.

“Above-market-rate housing is where the money is for developers,” says Mark Green of Sonoma County Conservation Action. “Santa Rosa built 3 percent of its affordable-housing need, and is at several hundred percent of above-market housing need for the next 20 years. That’s entirely a function of having a majority on the City Council who really don’t care about affordable housing.”

Santa Rosa, like most jurisdictions, has a housing allocation plan designed to produce more affordable housing by requiring developers to earmark a portion of every new project for lower-income residents. That way affordable housing gets built and ensures that it will be spread out throughout a city rather than ghettoized in one low-rent district.

But developers have found a way out.

“The bottom line is that after a period of time trying to make it work and listening to the development community explain that it wasn’t feasible, there were a number of exemptions, so most developers ended up paying a fee instead of building according to the ordinance,” says Santa Rosa’s director of community development, Wayne Goldberg.

By allowing in-lieu fees, Green says, developers get away with building exclusive housing enclaves and spending less than their fair share on affordable housing.

While in-lieu fees from Santa Rosa’s housing allocation program, along with state and federal money, have totaled $3.9 million since 1992 to help subsidize construction of 254 units of affordable housing in Santa Rosa, it has hardly made a dent.

The Association of Bay Area Governments, which in 1990 projected housing needs for each city and county in the region, estimated that Santa Rosa would need 3,437 units of low- and very-low-income housing. By 1995, Santa Rosa had issued permits for 405 units in those categories. In the above-moderate category, however, the picture is much rosier–at least for developers and residents with a healthy bank account. ABAG’s projection in that category was 1,151 units, and the city issued permits for 3,041 units by 1995–nearly triple ABAG’s projections.

“The marketplace doesn’t provide housing in low- and very-low-income [brackets] because the people you’re trying to reach can’t afford to pay the prices necessary to pay for construction. It requires some subsidy expenditure,” Goldberg says. “It’s difficult to find money to provide that.

“We don’t have enough resources to meet the need that’s defined.”

SANTA ROSA is hardly alone in slacking on housing for its poorest residents. The state housing-element law requires every city and county to come up with a housing plan certified by the state. At least Santa Rosa has a certified plan for affordable housing, even if the city couldn’t manage to keep pace with the growing demand. As of 1997, Sebastopol, Cloverdale, Rohnert Park, and the county itself did not have certified housing elements, according to ABAG senior regional planner Alex Amoroso.

That has angered some local housing advocates.

The county is facing a lawsuit over its housing element–or lack thereof, as some people say. At the crux of the lawsuit is not whether the unincorporated area has enough affordable housing–there is no law that requires jurisdictions to actually meet ABAG’s housing projections–but whether the county has made a good-faith effort in planning for development of affordable housing.

“There’s lots of land. It could be zoned and used for affordable housing, but the county has just been very reluctant,” says Santa Rosa attorney David Grabill, who filed the 1998 lawsuit on behalf of the Sonoma County Housing Advocacy Group, as well as three plaintiffs who have been unsuccessful in finding affordable housing. One of the plaintiffs, seriously disabled veteran Peter Huot, committed suicide in February, after struggling to find a landlord who would accept his subsidized-housing voucher.

“Take a drive out around Penngrove and the outlying areas of Windsor,” Grabill says. “In the rural unincorporated areas they have built much more above-moderate-income housing than they are required to build to satisfy the ABAG numbers.”

Sonoma County Community Development Commission chair Janie Walsh counters that the county has “a lot of affordable housing,” and faxes various lists that show 2,398 units of affordable housing for seniors, families, disabled residents, and farm workers, with another 1,282 units of low- and very-low-income housing.

In 1990, ABAG projected the county’s need for low- and very-low-income housing at 2,879 units.

The county government isn’t the only jurisdiction on the hot seat. Grabill says the Housing Advocacy Group is “watching very carefully” to see how Santa Rosa’s upcoming general plan update addresses affordable housing. “There may be litigation at some point,” he says. “You kind of wish it weren’t necessary to sue to get these local governments to understand the need for housing. Everybody agrees there’s a huge need for affordable housing in this county. It’s one of the more expensive places to live in the U.S.A. But when it gets down to specifics like, ‘Where are we going to put this 40-unit development?,’ the government people, they get very cold feet.”

Compounding the lack of affordable housing in the county is a projected boom in population and jobs. Sonoma County is expected to gain 116,000 residents by the year 2020, with Santa Rosa named as the third-fastest growing city in the Bay Area, according to an ABAG study released in December. In addition, the study projected more than 95,000 new jobs for the county in the next 20 years.

“The population is booming, the economy is booming, the jobs are being created at a faster pace than ever before,” Sternberg says. “Everybody looks at the IPOs and the high-salary jobs, but a lot of working folks don’t make that kind of money. Somebody sweeps up, somebody takes care of the landscape, somebody does word processing. Those are not high-paying jobs.”

“Those people,” Grabill agrees, “have to have a place to live.”

The situation is especially noticeable in Petaluma, where a 24 percent growth in telecommunications jobs in five years has attracted thousands of new employees to the already more expensive southern end of the county. Housing prices are up 15 percent, and apartments are tough to find, which in turn drives rents up.

“We’re getting a lot of traffic on our website, with people moving here letting us know a month or two in advance,” says Jim Provost, CEO of Alliance Property Management in Santa Rosa. “When they arrive, they are still just shocked at the small number of properties available and at the rents.”

The only newcomers who think Sonoma County is cheap are Silicon Valley refugees. “I’ve had a number of people relocate here. Their pay is not quite what it was, but the rental rates are half to one third what they are down there,” Provost says.

Provost isn’t optimistic about the market changing in the near future. “With the influx of jobs in Sonoma County, construction just cannot keep up with demand,” he says. “I still see solid rents through 2000, and as far as [ownerships of] houses are concerned, I don’t see any relief.”

WHILE STERNBERG likens the county’s housing woes to a critically ill patient beyond cure, he says there still is no excuse for giving up and pulling the plug.

“It’s depressing as hell, but that doesn’t mean you just sit around,” he says. Sternberg’s first suggestion is to implement a jobs/housing impact fee, modeled after a program in Sacramento that has raised more than $22 million in 10 years. The city assesses a fee for all new commercial and industrial development based on the number of employees the new office, factory, warehouse, or winery will attract.

While Sacramento’s commercial builders weren’t too happy with the program–they sued unsuccessfully to repeal it–housing advocates are delighted at the outcome. “It has helped bring a balance to housing development so that as industrial and commercial development take place, the people who work in those industries have a place to live,” Grabill says.

Other ideas include raising the transient occupancy tax charged by hotels and putting the funds toward affordable housing. Or offering density bonuses, allowing low-income-housing developers to build more units on a parcel than is allowed by zoning laws. Or offering fee waivers for low-income projects. Each solution, of course, comes with its own set of problems, not the least of which is that, for some people, more housing–affordable or not–isn’t a positive step. More housing means more people for a county already feeling enormous pressure to curb growth–and one that four years ago became the first in the nation to adopt comprehensive urban growth boundaries.

Three Bay Area communities in Alameda and Contra Costa counties faced anti-sprawl ballot initiatives last fall that sought to require voter approval of even modest-sized developments. All three were rejected, but more are likely to be on next year’s ballot, a sign that housing needs and growth control may soon be in direct competition.

Some slow-growth folks might see Sonoma County’s failure to provide enough housing as a “good thing,” says Green. “But it’s not really. Sooner or later we’re going to be required to meet affordable-housing demand; then we’ll have to build those on top of the above-market-rate housing.

“There are a lot of strategies out there to make affordable hous-ing possible,” he adds. “If it were as high a priority for Santa Rosa as, for example, it was to pound the Geysers [wastewater] project through, it would get done.

“They should just stop issuing permits for above-market-rate projects and just build affordable housing.”

From the January 6-12, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.