Get Naked

Hangin’ out (literally) at NudeFest ’99

By Chris Wright

I’m leaning my elbows on a bartop, sipping Fosters Lager from a plastic cup. Nothing unusual about that. Two middle-aged guys beside me are having a boisterous conversation: “He shoulda kept his damn mouth shut!” Just regular guys talking regular guy stuff. Less regular is the fact that the two guys are naked. Come to that, so am I. Usually this realization would mark the point where I’d wake up, sweat beading my brow. But not today.

The really strange thing is, it’s OK.

By this point, I’ve already been hanging out (literally) at Berkshire Vista for a good few hours. Berkshire Vista is a nudist resort located in the mountains of Massachusetts; I’d arrived early that morning, eagerly anticipating NudeFest ’99, the 52nd annual convention of the Eastern Sunbathing Association .

What I hadn’t anticipated was my initial discomfort at the sight of the teeming, tawny nakedness all around me–or having to stand around waiting for my hosts, studiously averting my eyes, making small talk with a partly clad T-shirt vendor.

“Are those T-shirts for sale?” I ask. The vendor smiles and nods. After 10 excruciating minutes, my hosts arrive: Susan Weaver, public-affairs chair for the American Association for Nude Recreation, and Linda Pace, AANR marketing director. Both are wearing sarongs.

The big question comes almost right away: “Do you want to take your clothes off?”

In the interest of journalistic integrity, I’d already decided to say yes. So I do it–shirt, socks, shorts–and there I am, standing in the middle of a field, wearing nothing but a pair of red Converse sneakers and carrying a black briefcase. As if I don’t already feel awkward enough, a passing woman points at my ass, proclaiming, “Look! A cottontail!” Great.

Laughing, Weaver and Pace strip, and the three of us jiggle down a small hill, on our way to my first stop of the day. I’d been hoping for something a bit racy to start with–the conven-tion agenda includes Olympic training, a seniors’ swim, and nude bacon and eggs breakfast–but those had taken place earlier.

What I get is an ESA membership-committee meeting.

About 50 people in various stages of undress sit and stand under a wooden structure in a section of the resort known as the Ghetto. I honestly don’t know where to look–or, more important, where not to. Particularly unsettling, for some reason, are the guys who aren’t quite nude, their todgers peeking out below the hems of their T-shirts.

As Susan introduces me to the meeting, announcing that I am a “first-timer,” the delegates give me a big round of applause, which is actually more disconcerting than the cottontail incident. Clutching my briefcase before me, I scamper to the nearest table and settle down to watch the proceedings.

For the next hour I nod thoughtfully, gaze intently into the face of each speaker, and scribble notes such as “the power of public advertising” and “Jesus, they’re huge.”

When I think nudism, I generally tend to think nude beach. So how did I come to find myself in the middle of the mountains, attending a legislative assembly, listening to talk of budget proposals and outreach strategies?

Since its inception in 1931, AANR has grown into a massive organization boasting 50,000 members, 236 clubs, and seven regional branches. In fact, the organization is experiencing growing pains. At the meeting, discussions about where to put the proliferating legions of nudists generate almost as many solutions as there are delegates.

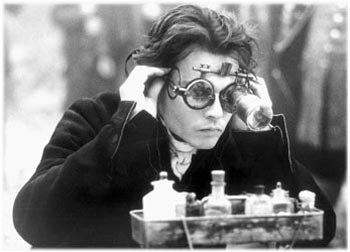

The task of bringing all this diversity together falls to Greg Smith, the AANR’s national president. Smith has something of a young Hunter S. Thompson look about him. Slim, tanned, with a shaven head and sunglasses, he serial-smokes mini cigars and presides over the meeting with cool authority. Even though I am still in the omigod stage, when Smith speaks it’s quite possible to forget the pecker beneath the mike. And Smith speaks quite a lot.

At one point, as the president takes center stage yet again, a delegate sings under his breath: “Here he comes to save the day!”

AFTER THE MEETING, Smith sits across from me, rests his elbows on the table, and says, almost immediately, “I have nothing to hide.”

Quite.

A retired naval officer, Smith currently drives a school bus in Bethel Park, Pa. He’s less interested in talking about his professional life, however, than in touting an annual nudist volleyball tournament he arranges. “Last year,” he says proudly, “we had 95 to 100 teams, 2,000 people.”

As with many of the people I meet today, nudism is not merely an interest for Smith, nor even a lifestyle. It’s a vocation, a creed. He seems particularly proud of his record as AANR’s leader, speaking of how nudism is “becoming more and more mainstream every day,” of how he has helped the organization “enter into the 21st century,” of the constant barrage of e-mail and faxes he receives, the twice-weekly meetings he must attend.

Smith admits that the logistical headaches of bringing a nation of nudists together can make the president’s role a tough one. “You can’t afford to get upset,” he says. “If you do, you’re in the wrong job.” The AANR has presidential elections slated for the year 2000, and I ask Smith who his main challenger is.

“When the president is doing a good job, there is no competition,” he says, lighting up another cigar. “I expect to be re-elected.”

And so there we are: two men, buck-naked, discussing institutional politics. At one point, Marci Lott, Smith’s fiancée, glides over. The couple are planning a nude wedding sometime this year, they say (“at least the bridesmaids will all match”). Lott–a trainee flight attendant–is blond, large-breasted, and wears a sheer white wrap around her waist. I am mortified–helplessly so–to note that she is very sexy.

Sex, however, plays little part in your average nudist camp. And that’s not only because many nudists resemble your grandparents.

When you come down to it, the symbolic link between nudity and sexual intercourse rests on a pretty banal concept: I’m ready. But when everyone is nude, that link is somehow broken. Sex has no place at a nudist resort precisely because the guests are naked.

As the saying goes: “We’re nude, not lewd.”

Indeed, the only hint of prurience I get the whole day is from a guy who admits to having gotten interested in nudism when, in his teens, he bought a copy of Sunshine & Health. Which doesn’t necessarily mean that sex is far from the minds of nudists–at least in an institutional sense. While the terms respect, acceptance, and wholesome are thrown about by AANR representatives like rice at a wedding, the word sex is tirelessly avoided.

But, as always, it looms all the larger for its absence.

Aware that many people view organized nudity with a suspicious eye (or worse, think Wey-hey-hey!), the organization goes to extreme lengths to project a socially responsible, clean-living image. It organizes blood drives, clothing drives, and beach cleanups. So conscious is the organization of its public image that Weaver runs media-training sessions during which AANR workers learn to fend off salacious and cynical media inquiries with quotable epigrams (“Shed your cares with your clothes”).

Weaver will also turn down media requests from potentially unfriendly sources.

“Why would we deal with someone who’s going to make fun of us?” she asks.

WHAT IS MOST surprising about today’s gathering, however, is that despite all the wholesomeness, most of the nudists are far from being the crunchy, touchy-feely bunch I had anticipated. When I arrived at Berkshire Vista, I tucked my cigarettes away, fearing a lynching if anyone saw them.

But fellow smokers abound, and the clubhouse bar does a thriving business. There’s barely a hint of sanctimony.

Indeed, rubbing elbows with the guys in the bar feels like being back in the city–that is, if elbows were all we were rubbing. Some of the nudists even indulge in saucy banter when Linda Pace gingerly steps into the club’s swimming pool. “It’s cold!” she says. “Love those bumps.”

“So do we,” replies one man, arousing bursts of laughter all around. To say that Linda Pace is a good sport would be to understate the matter. A full-figured woman far too young-looking to be the mother of three 20-something children, Pace is energetic, witty, and as prolific a smoker as I am. As a group of us sit on a deck having lunch, Pace laments the fact that she can’t finish her burger. “My eyes were bigger than my stomach,” she says. Then, without skipping a beat, she looks at her stomach and says, “I guess you can only say that when you have clothes on.”

PACE used to run a halfway house for troubled teens; now she is a full-time nudist. I knew I was at ease with the AANR’s marketing director when I stopped not noticing her breasts, when I was able to run my eyes over them as easily as I would a lapel. Many people espouse the old “body acceptance” nugget during my time at the convention, but Pace really brings it home for me.

“As a woman who has three kids,” she says, “my body is a road map that leads back to my children. Me without clothes on is not going to make the cover of Cosmo, but with this group I feel beautiful.”

So do I.

As one who enjoys the odd pint, my body is a road map that leads back to the Sam Adams brewery. But here–and not only because the majority of the people are in worse shape than I am–I feel completely comfortable. Or at least I’m beginning to. Most of the time.

Nearly.

During a game of volleyball, every now and then I think, “Hey, that person who just spiked me is naked.” Or worse, when saying hello to a passing kid: “Hey, I’m naked.” At one point, a guy says something about the government being “hard on” nudists and I think, “Hard on!” as if the very words could trigger a disastrous bout of tumescence. And it does feel a little weird to be showering beside Susan Weaver. Then again, after you’ve soaped up beside a publicist, you’re pretty much ready for anything.

As the day draws to a close, I’m very nearly at ease, dangling my tackle in a variety of settings as if it’s the most natural thing in the world.

And, of course, it is.

As I prepare to leave my newfound nudist friends, a poolside wine-and-cheese reception is in full swing, and I feel a little stab of regret. Later tonight they’ll be having a disco dance, complete with DJ. I have visions of a hundred nudists doing the Macarena. But I have stuff to do back in the city and a long drive ahead of me, so I decamp.

People I’ve met over the day hug me, give me little presents, assure me we’ll meet again.

I’m a sentimental guy–I hate goodbyes–but there’s something else bothering me. It’s strange, but after a day in the buff, I am appalled by the prospect of putting my clothes back on. Then again, maybe it’s not such a bad idea.

As I stand beside the pool, a guy comes over to inspect my backside, bending slightly for a better look, and inhales sharply through his teeth.

“Put some tea bags on that,” he says. “Or some vinegar. You’re going to need it.” I twist and take a look. He’s right. According to people I’ve met today, Thoreau was a nudist. Ben Franklin was a nudist. FDR was a nudist. Jesus was a nudist. Now, it seems, so am I.

And I have the sunburned butt to prove it.

From the September 2-8, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.