Talking Pictures

Local Film discussion groups bring Hollywood down to Earth

By David Templeton

“HAVE YOU EVER noticed,” asks Gary Sherwood, “that no one in the movies ever takes a blow to the head unless they’re standing in front of a spotless white wall?”

Sherwood is in fine form tonight, musing aloud about the bloody climactic scene in the Oscar-nominated American Beauty. Around him are gathered a dozen or so fellow film buffs, enthusiastically discussing this year’s Academy Award nominations, in the back of Barnes & Noble in downtown Santa Rosa.

Outside it’s raining cats and dogs, but deep inside the sprawling bookstore, the participants are enthusiastically defending or bitterly denouncing the Academy’s choices. The conversation is fast-paced and unpredictable.

“How come John Turturro didn’t get nominated for doing the voice of the voice of the dog in Summer of Sam?” someone wants to know.

Upon noticing that The Phantom Menace didn’t receive any major nominations, one woman remarks, “I feel sorry for George Lucas.”

“Don’t do that!” Sherwood exclaims, eyes widening in make-believe shock. “Don’t ever feel sorry for George Lucas.”

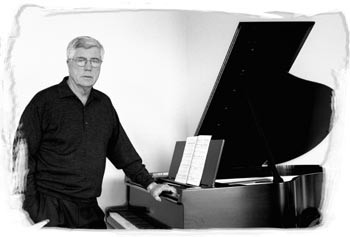

THAT’S THE SCENE every other Tuesday night, when some of Sonoma County’s most dedicated film buffs have an ongoing appointment, gathering here to take part in Sherwood’s Reel Time film discussion group.

Sherwood, a 35-year-old local screenwriter who teaches screenwriting courses at adult schools in Petaluma and in Sonoma and also hosts a midnight radio show, “Rhythm and Blues Rendezvous,” on KRCB on Fridays, began the popular open-forum discussions in January of 1996. A hit from the start, the group has an average attendance that now runs between 20 and 40 people, though there have been some big spikes. Over 100 people were on hand when Sonoma director and animator John Lasseter (Toy Story; A Bug’s Life) made a special guest appearance last year.

According to Sherwood, who combines the best elements of a walking film encyclopedia and a stand-up comic, his group’s attendees are a mixed bunch. They range from hardcore cineastes like himself–people who see every movie, know which directors went to which film schools, and can name their favorite key grips–to those less obsessive film fans who enjoy films but hardly live and die by them.

“There’s always a fun group dynamic, with lots of lively argument and debate,” says faithful attendee Diane McCurdy, a longtime Santa Rosa movie enthusiast and outspoken KRCB radio film critic. “It’s always entertaining. I’m addicted.”

She’s not alone. Now four years old and counting, Reel Time ranks as Barnes & Noble’s longest-running in-store event. Even filmmaker Brian DePalma, visiting the area a few years ago to scout locations for a film, was drawn to attend. Stories are still being told about the night the famous director, unrecognized at first, sat in on a spirited discussion of Steven Spielberg, not revealing his identity until the very end.

Diversity, Sherwood says, is the key to the group’s success. But there’s also no doubt that many of the longtime members are here, at least in part, because of Sherwood himself.

“We really like Gary,” says Ray Hoey. “A lot of the time, he’s more entertaining than the movies we talk about.”

FILM GROUPS such as Reel Time are on the rise. Though not as common as book discussion groups–which have become so popular in recent years that publishers are now printing special “book group” editions of certain titles–film discussion groups are starting to pop up all across the country, with an unusual number appearing in our own backyard.

For over 10 years now, Jim and Shirley Costa have been participating in film discussion groups, organizing “cinema circles” from San Diego to Ashland to their current home in Rohnert Park.

Sponsored by the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Santa Rosa–of which the Costas are members–the film-savvy twosome’s latest movie group, called “We’re Talking Pictures,” meets monthly in the homes of regular participants, where the conversations tend to be lively, passionate, and political.

“We try to select films that deal with social issues,” says Shirley. “After The Green Mile, we had quite a discussion about capital punishment. Smoke Signals gave us things to talk about, of course. And Eyes Wide Shut provoked a lot of discussion. A lot of people didn’t understand it, a lot of them didn’t like it–but they sure had a lot to say about it.”

Each month someone chooses a film for discussion, and those who’ve seen it gather to talk about it. Costa admits that she enjoys the discussion groups best when everyone sees the chosen film, whether it’s a film they’d normally choose to see or not. Like Steven Soderbergh’s Kafka.

“No one wanted to see it at first,” she admits, adding that the ensuing conversation was one of the richest she’d ever experienced.

“Some of the most interesting films I’ve ever seen were films I’d never have seen if someone hadn’t made me,” she says with a laugh. “The whole thing about going to the movies is to open yourself up to a new experience, to take on a new way of seeing the world.”

THAT SAME philosophy, more or less, motivates the weekly film-and-discussion series that started at Petaluma City Hall last November.

Run by a collective of volunteers representing four organizations–Petaluma Progressives, Dialogue on Race, Sustainable Petaluma, and Independent Filmmakers–the increasingly popular program screens a different documentary film each Friday night. The movie is followed by a moderated discussion, which often features invited guests familiar with the issues of the film.

Recent events have included films about Jack Kerouac and the poet Rumi.

“The discussions are always pretty exciting,” says Beth Meredith, one of the organizers. “It’s unpredictable. It’s great. That’s why we do it. Mainly, we’re doing this to raise awareness of important issues. The discussions afterwards, as the community comes together to share different perspectives, is where the exciting stuff happens.”

“To my mind,” adds fellow organizer Natalie Peck, “this is one of the most exciting things happening in the county.”

For information on the Unitarian Universalist “We’re Talking Pictures” group, call Shirley Costa at 795-4877; and on the Petaluma series, call 763-1532.

From the March 16-22, 2000, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.