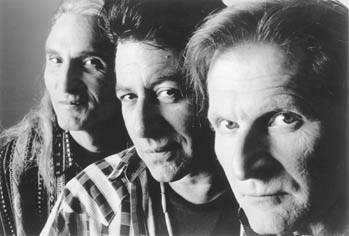

Winds of change: Marin author Gerald Nicosia chronicles the battles that Vietnam vets had to fight, on the inside and in the world.

The War at Home

Gerald Nicosia chronicles struggles of Viet vets

By Jonah Raskin

GERALD NICOSIA never set foot in Vietnam and never served a single day in the military. But after spending much of the last 12 years of his life in the company of volatile Vietnam veterans, he often feels that he’s one of them.

“I feel like I fought in the war,” he says, as we talk in the cozy house on a quiet residential street in Corte Madera, where he lives with his wife and two children.

It’s here that Nicosia wrote Home to War (Crown; $30), a big, heartfelt book that chronicles the battles veterans had to fight–for peace, for health care, for their own dignity–when they returned to the states from the jungles of Southeast Asia.

More than 600 pages long and packed with poignant narratives about the veterans themselves, often in their own explosive words, Home to War is a beautifully told work of contemporary history and a lyrical anti-war epic.

Nicosia is the author of four previous books, including Memory Babe, his award-winning biography of Jack Kerouac. But Home to War feels like his masterwork, the book he had to write to be at peace with himself and with the veterans who brought the war, willy-nilly, into his own life as a teacher and biographer.

“I started it in 1988,” Nicosia says as he sits in the cramped study that boasts photos of Jack London and Jack Kerouac, his long-time literary heroes.

“I interviewed hundreds of people, many of whom have since died of drug overdoses, agent-orange cancers, and suicide,” he recalls. “I’ve been through four publishers–Norton, Grove, Holt, and Crown. If I had known it was going to be this difficult, I might not have started it in the first place.”

In fact, Home to War has been a lot longer in the making than just 12 years. You might say that Nicosia began his journey in 1965, when he was a bright high school student in Berwyn, Ill.–“a redneck, racist place” he calls it–where boys were raised to fight and die for their country.

“I went to a Catholic church where the priest told us it was our moral duty to go to Vietnam and kill Communists,” Nicosia says. “In those days and in that place, you weren’t supposed to read the Bible yourself. The priest was supposed to interpret it for you. But I bought my own Bible, and discovered that St. Matthew says we’re supposed to love our enemies, a sermon I never heard in church.”

Henry David Thoreau’s essay “Civil Disobedience” also inspired him, much as it inspired the civil rights protesters of the 1960s. But it was Walden–and Thoreau’s message to heed a “different drummer”–that made Nicosia a pacifist and impelled him to resist the war in Vietnam.

“Walden blew me away,” he says. “It was a liberating book that taught me to make my own declaration of independence. From Thoreau, I learned the political power of books. I decided I was going to be a writer one day, too.”

In 1967, when he turned 18 and became eligible for the draft, Nicosia followed the dictates of his own conscience and joined the ranks of the anti-war movement at the University of Illinois in Chicago, though he never became a visible leader or a spokesman.

His own father urged him to enlist and find a safe job far from the front, but even that option seemed like collaborating with the war-makers, and Nicosia made plans to go into exile in Canada.

Then, in 1971, the draft ended and, like thousands of other young men ripe for military service, Nicosia was off the hook, and finally able to sleep at night. Following graduation, he taught rhetoric at his alma mater and began to learn about Vietnam by meeting veterans face to face.

“One of my best students was a black GI named Al Nellums,” Nicosia says. “In my English class he wrote an essay titled ‘The First Man I Ever Killed,’ in which he describes how he pulled out a pistol and shot, at point-blank range, a Viet Cong guerrilla who was trying to kill him. ‘How do I live with that?’ he wanted to know.

“It was a question I couldn’t answer,” Nicosia continues. “But I began to see how the war had followed the men home, and how they couldn’t shake it.”

Other veterans, including Bill Troutman–who served in Vietnam during the traumatic Tet offensive of 1968–opened Nicosia’s eyes to a war that continued to rage inside.

“My own youth had been traumatized by Vietnam,” Nicosia says. “I had been angry and then I cooled, but for the vets the anger was still red-hot and that was a revelation.”

In 1984, a year after the publication of his monumental biography of Jack Kerouac, Nicosia met Ron Kovic, and though they had taken very different paths in life, they fast became the closest of friends. The author of Born on the Fourth of July (the memoir that Oliver Stone made into a movie), Kovic was then, and probably is still today, the best-known Vietnam veteran–aside from former Nebraska Sen. Bob Kerrey, who made headlines last month with controversial revelations about his military record.

Kovic is also probably the most vocal anti-war soldier of his generation. Wounded in battle in 1968, and a paraplegic ever since, Kovic has spent more than half his life in a wheelchair.

“I hung out with Ron when he lived in a cottage in Sausalito,” Nicosia says. “In public he put up a good front, but in private I got to see his wounds, his withered legs, his gloom and hatred. ‘I wish I could put all of you in chairs so that you’d suffer like I suffer,’ he once said. It was only a moment and it passed, but it was real, too.”

OVER THE YEARS, there were other vets who touched Nicosia, including Bobby Waddell, who became a heroin addict while serving in the Air Force in Vietnam and who later spent four years in prison in California on drug charges.

“I’d visit him in Tehachapi, and he’d say, ‘You’ve got to tell our story. Please write our story,’ ” Nicosia recalls. “After he practically begged me to write the book I couldn’t refuse.”

In Home to War, Nicosia tells heartbreaking stories about Bobby Waddell, Ron Kovic, and a platoon-sized outfit of other soldiers–without either patronizing them or idealizing them.

He also describes the veterans’ fragile organizations, including Vietnam Veterans Against the War and the vets’ ongoing efforts to heal their own wounds and the wounds of the nation itself.

Reading Home to War reminded me how much the veterans had in common with other activists from that era. Like the yippies, the Black Panthers, and radical feminist groups, activist veterans developed a knack for creative guerrilla theater that attracted the attention of the media and aroused the moral conscience of the country. Descending on Washington, D.C., in 1971 and returning their military medals was as dramatic an anti-war gesture as any in the history of the American anti-war movement, and Nicosia describes it in vivid detail.

Moreover, like other radical groups of the 1960s and 1970s, the vets were targets of U.S. government harassment and persecution. FBI agents spied on them, the Department of Justice indicted them on charges of conspiracy–there was a major trial in Gainsville, Fla.–and the White House treated them as pawns in the game of politics.

Still, if there’s a main villain in Nicosia’s book, it’s the Veterans Administration, the bureaucratic agency that ought to have served as a staunch advocate for the veterans, but that often ignored them, neglected them, shipped them off to living deaths in “miserably dirty, understaffed hospitals.” For many of the men who appear in this disturbing book, coming home from Vietnam proved to be a lot more horrible an experience than fighting in the war itself.

At 52, Nicosia is still a pacifist, and still listening to the different drummer that Thoreau describes in Walden.

“I hope that by remembering Vietnam and the vets, we’ll realize that we shouldn’t make war ever again,” he says. “In Vietnam, we never tried to win the hearts and the minds of the people. We weren’t there to save a democracy, but to destroy a country. The vets brought that lesson home from the front. They were inspirational.

“The best of them showed us that you can turn trauma around, cope with pain, and live productive lives.”

Jonah Raskin is a communications professor at Sonoma State University and the author of ‘For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman.’

From the May 17-23, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.

© Metro Publishing Inc.