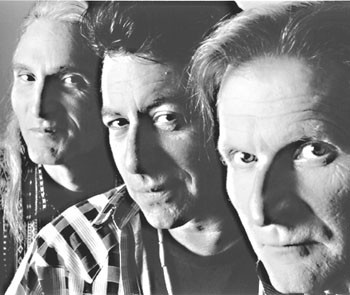

Photograph by Michael Amsler

Success Story: Tom Gaffey, manager of the Phoenix, has successfully run an all-ages club–but not without problems. An earthquake retrofit is his next challenge.

Rock Unsteady

North Bay bands–and music fans–find themselves all dressed up with nowhere to go

By Sara Bir

On a recent Saturday at the Phoenix Theatre in Petaluma, a larger crowd than usual is gathered outside. The gothic-punk band AFI is playing, and the kids have come out in their full glory: eyeliner, greasy, dyed black hair, and torn fishnet stockings are in abundance. AFI recently signed with the major record label DreamWorks, and this two-night gig at the Phoenix is a wonderfully circular event: the band, who are originally from Ukiah, basically cut their musical teeth playing this place nearly 10 years ago. They even wrote a song about it, “The Days of the Phoenix.”

So, in an overly dramatic sense, it could be said that without the Phoenix, DreamWorks would not have a hot, new band on their hands, MTV2 would be missing a video, and–most important–the kids waiting to hear AFI play would be stuck with no big reason to get excited tonight. When you are 16 and music matters more than almost anything in the world, there’s no better place to be than with your friends watching a band play their hearts out for you.

The Phoenix fought long and hard to stay open. Four telecom engineers acted the angel two years ago, swooping in and saving the venerable all-ages venue from a certain demise. Others have not had such divine intervention. Fallen Sonoma County venues line the past five years like a row of headstones in a cemetery: Santa Rosa lost the Moonlight, Rumors, and Mudds. Last year it was the Inn of the Beginning in Cotati. The latest casualty is Jessie Jean’s Coffee Beans, an all-ages live music emporium and coffee shop in Santa Rosa. They have announced that they will be closing their doors at the end of the month.

Anyone would expect a large city like San Francisco, Seattle, or Chicago to have an active music community, but when presented with evidence of thriving scenes in places like Lawrence, Kan. or Omaha, Neb., people are often surprised. Sonoma County, with half a million residents, many of them forward-thinking and creative, sort of falls between the two extremes.

Jon Fee, who plays bass in the Rum Diary out of Cotati and runs Don Lee records (which has put out two compilations featuring Bay Area indie bands, translation: music and translation: music 2) says, “Sonoma County measures up pretty well with similar areas across America. It has most of the key elements to produce a thriving music scene: it’s of a good size, it’s close to a cosmopolitan city, it’s affordable, there are good record stores, great music equipment shops, and a couple of colleges. What we are lacking is an established venue.” True, with Sonoma State University and Santa Rosa Junior College, there’s certainly potential for an audience to support a more stable roster of venues, especially ones geared toward a younger demographic.

“There’s definitely a huge void to be filled here, considering the amount of homegrown talent and the obvious demand for it,” says 23-year-old Dylan Abbott, who lives in Petaluma and plays in the indie-rock band Superficial Hero. “There are hundreds of musicians playing original music locally, and with only a handful of venues available to the younger audience that is the most passionate about that music, 90 percent of those bands are doomed to either go unheard or forced to play away from home.”

Perhaps that’s why we need a larger spectrum of all-ages venues–because it’s almost as if the Sonoma County music scene, which has so much talent and diversity and potential, is all dressed up with nowhere to go.

Between Rock and a Hard Place

Keith Givens is in a tight spot, the one club owners are all too often squeezed into: he’s not making enough money running his coffee shop, Jessie Jean’s Coffee Beans in Santa Rosa on Mendocino Avenue, right across the street from the Junior College and Santa Rosa High School, to keep it open. “The music’s been the only thing keeping the money coming in,” he says. “The coffee and all that’s died off, and schools are out.”

Givens opened Jessie Jean’s in October 2000. Prior to that, he had an espresso cart in front of G&G Market in Santa Rosa. From the get-go, Jessie Jean’s was intended as a live music venue. “I started out with blues and jazz, folk dancing and square dancing,” he says. “Now we have every show imaginable . . . all the punk shows, metal shows. It’s about 130 bands a month.”

Jessie Jean’s stepped up when Sonoma County lost its primary midsize all-ages venue last year, the Inn of the Beginning in Cotati. “When the Inn closed down, we lost a great venue that was able to bring in smaller, independent touring bands and was willing to give young local musicians a stage to play on for all-ages crowds,” says Abbott. “Jessie Jean’s had sort of filled that void, catering to a similar audience with an equally diverse range of styles.”

And it did not go unnoticed. “We get calls from everywhere in the United States to play shows here,” Givens says. “Someone called from Pennsylvania yesterday . . . Arizona, South Carolina, Kansas.”

What Jessie Jean’s doesn’t have are hip-hop and techno shows, mostly because of a small handful of incidents involving fighting and underage drinking–all happening outside the club. “The kids don’t know how to behave themselves–there’s 100 that do, and 20 that don’t,” says Givens, who does not believe that the police zero in on rock venues specifically. “They don’t target anything unless you draw their attention to it. The police department’s been pretty cool. They want you to do exactly what you’re asked of, and that’s to have ample security to make sure the kids are safe. If you do all that, they leave you alone.”

In some cases, just keeping on top of what’s going on inside and outside has been enough to curb trouble. “We opened this place, there was graffiti for four months,” recalls Givens. “We busted some guy doing it, the cops busted two other people doing it. We painted the walls, and the kids started showing up–the ones that have been here doing the shows–and there hasn’t been any graffiti on our building since . . . actually, on this whole block.

“I get parents, every week they come by and give us their telephone number if their kid’s gonna be here past 11. And if you’ve got 150 kids running around here and you got 10 of them outside and you need to call, then that’s what we do. It’s about keeping the kids safe, and they know it’s like a big babysitter.”

The kids look out for Jessie Jean’s, too. “They come up to me and say, ‘Keith, that guy’s out there starting shit again who got kicked out of here two months ago.’ Or ‘Keith, someone’s drinking out there in front of the shop.”

“The kids in the evening are beautiful,” says Penny Caswell, who also runs Jessie Jean’s and is Givens’ fiancée. “They’re all here to have fun and try to keep the place open. Those kids put 210 percent into their music.”

“I enjoy all of them. We aren’t just here for the bands; we’re here for the kids. Everything we’ve done with the shows and the kids . . . there isn’t anywhere else for them to go. There really isn’t–unless there’s alcohol there,” Givens says.

Possibly Jessie Jean’s didn’t make it because it’s a more teen-oriented venue. “Say you have 200 people in here, [only] 25 people will buy stuff,” Givens explains. “A dollar soda or a dollar water–which is $30 on our $200 show, and you’re paying the bands half. . . . This place needed $460 a day all the way through, and when the schools are out, it drops to $120 a day, and we’re here for 18 hours. It’s hard to keep a venue like that open.”

Jessie Jean’s had been putting on benefit shows for six months to keep the place open. “All the money goes towards us, $500 or $700,” Givens says. “Some kids went out and made their own flyers, went out and collected money to try to keep the place open. But there’s not much you can do when you have three days to pay or get served and move out. If someone walks through here with $4,700, we’d still be open.”

Even if the end is looming, Givens and Caswell would like to continue doing events as long as possible–“to the end of June, we hope,” Givens says. “I definitely want to thank all of the kids for supporting us.”

End of the Beginning

“God, I loved the Inn,” sighs Michael Houghton, editor of the bimonthly music magazine Section M, which was initially devoted to North Bay underground music but has since moved on to focus on the entire Bay Area. Section M has been coproducing shows in venues such as the Phoenix, Jessie Jean’s, and the Old Vic for nearly three years but mainly used the Inn of the Beginning as its base for shows.

“It had become such a home as far as putting on shows and going just to feel that community,” Houghton says. “It was pretty much the perfect combination of factors: geographically in the middle of Sonoma County so everyone could go, and it was all-ages as well as serving beer for the older folk, and with a great sound guy and system. It’s just so much harder to get people to come out to shows without the Inn. It was a pretty big blow to the scene at the time.”

So if the Inn of the Beginning had so much going for it, why did it close? First off, the Inn took a severe financial hit when Sparks, the fine-dining vegan restaurant that opened in the space to supplement the club, didn’t work out in that location. Sparks later moved to Guerneville. But another reason was perhaps longer in the making, a slow burn that built up with a series of kids getting busted for drugs and drinking in the parking lot outside of the club.

“The amount of pressure that the police put on that club was just totally unreasonable,” Houghton says. “Instead of trying to help with whatever problems they perceived, especially underage drinking, they just went out of their way to make the club suffer however they could.” That included fines and periods of suspending the Inn’s liquor license.

Abbott agrees. “The Inn and Jessie Jean’s are two prime examples of high-profile, all-ages venues that faced a large amount of resistance and outright hostility from local law enforcement and government. I understand the need to go after things like underage drinking and drug use, but it seems like these two clubs faced a disproportionate amount of scrutiny and regulation based on a handful of isolated incidents.”

“Clubs give kids music, community, and creativity as something they should aspire to,” Houghton points out. “You shut that down and you shut down dreams, and you leave them with the choice between boredom and self-medicated boredom. I just don’t understand the twisted politics of situations like that,” says Houghton.

But isn’t it the same story in any town that has young adults heading out to shows? “The man is always going to crack down,” says Fee. “That is what he’s there for. The man is like a big grizzly bear. No grizzly is just going to sit back and let you pull on his tail or leave beer bottles and cans in his cave.”

“I’d like to see more support from the city councils and police for something that is helping the kids and should be making their job easier,” Houghton says. “They ought to be working with the promoters to help provide a safe place for kids, instead of against them. These kids are good kids.”

There’s a There There

Is there even a scene here to begin with? It depends on which people you talk to, how old they are, and what kind of music they like. The past five years have proved that the musical soil in Sonoma County is pretty damn fertile: new bands spring up all the time, and a lot of them–such as punkers Tsunami Bomb, indie-rockers Benton Falls, and local faves the Velvet Teen–tour regularly.

“I think a lot of kids from Sonoma County go to shows up here and end up getting tuned in to what’s happening in the Bay Area as sort of an outgrowth of that. It’s rare that I go to a show in San Francisco or Berkeley and don’t see anyone who I recognize from shows around here,” Abbott says. “On the flip side of that, it’s been rare for me to meet people from out of town at local shows, unless there’s a touring band with a larger draw playing locally. So it seems like kids around here are tuned in to things enough that they’ll go to shows locally and in the rest of the area, but there’s not really any people making Sonoma County a destination for underground music.”

Which, to a point, it could be–at least for lesser-known touring bands, who often look to play in satellite locations close to larger cities so they can book as many dates as possible when in one region. If a band plays a town and picks up that the audience is into the music and having a good time, they’ll remember that club and want to go back there.

“When smaller touring bands or bands from San Francisco come to play shows in Sonoma County, they generally think it’s going to be awesome because they’ve read a copy of Section M and they think we have a really devoted music scene,” says Fee. “What we have is a solid amount of support for local bands but not so much for smaller touring bands.”

What about Marin County? Plenty of clubs are going strong there–Sweetwater in Mill Valley, 19 Broadway in Fairfax, and New George’s in San Rafael. But even though the space for live music exists, the focus is mostly on retro and folk acts, which aren’t big with all-ages crowds. As Abbott says, “I don’t know . . . I’ve never been to a show in Marin. That would just be . . . wrong.”

“If you live in Marin, you are close enough to go to shows in San Francisco,” says Fee. “It’s only 20 minutes away, and it’s well worth the drive.”

The aptly named Phoenix, though risen, still faces adversity. The building is in need of an earthquake retrofit, which was slated for this summer, an eventuality that would have put a kink in more than a few music fans’ summers. But if you’ve heard a collective sigh of relief, that’s because the retrofit has been postponed yet again. “We’re still here,” says Tom Gaffey, manager of the Phoenix since 1983 and a familiar face to many. “We’ll have to eventually get it done, but we’ll still be around for a little while. They’re looking to start their construction project maybe the beginning of next year. We’re booked through the summer.”

In the meantime, the Phoenix–and Gaffey–will continue marching on. He certainly seems to be enthusiastic. “I finally got my prescription for Prilosec [heartburn medicine], so it’s going to be a great summer!” he chimes. “And you can quote me on that.”

“Things are slowly growing back,” says Houghton. “We have a lot of amazing new bands coming up in the scene, and the shows just keep getting bigger. So something is going right.”

It’s up to us to keep it that way.

From the June 13-19, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.

© Metro Publishing Inc.