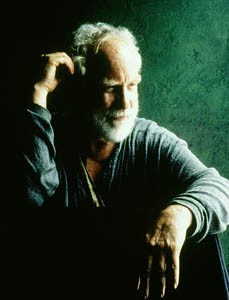

Man and Beast: Stuart Schroeder tames nature with the help of Sparky and Ike.

Plowing Forward

At Stone Horse Farm, the tractor gathers dust

By M. V. Wood

Just as the sun sets, the wind picks up and the birds start calling out in unison. Some of the calls come from atop the old oak tree–the one Denise Cadman and Stuart Schroeder were married beneath.

“I love that tree,” Cadman says. And I’m sure she doesn’t mean she’s fond of it or that she simply likes the way it looks. “When people start feeling that having an oak tree in their front yard is going to enhance their lives more than having a new car in their driveway ever could, that’s the day things will start shifting in the world.” She says this with no holier-than-thou judgment in her voice. No anger. She just says it as a wish.

Schroeder would surely agree. But he’d probably throw in the idea that people would also be happier with a couple of horses in their yard as well. Right now, he’s leading one of his two draft horses to the other side of the house for a drink. The western end of the sky is still glowing with pink streaks, and the silhouettes of man and horse look like something from a Currier and Ives print.

If you drive by Stone Horse Farm on Occidental Road, between Sebastopol and Santa Rosa, you might see Schroeder farming the land with his horses, Sparky and Ike. Schroeder owns an assortment of old farming implements, some dating back almost to the turn of the century, which he bought at auctions and other sales. He hitches the instruments up to his two Percheron horses, and that’s how he does all the plowing, mowing, and moving on the farm. The harvest is then sold at the Sebastopol Farmers’ Market.

When the horse is done drinking, Schroeder returns to the picnic table. The outdoor spot seems to serve as the hub of their home life, at least during the warmer months. Their two-year-old daughter, Rosalie, plays nearby, searching for bugs.

Schroeder, 41, sits down, his eyes scanning the small, family farm. “Sometimes people ask me why I have such a sense of nostalgia,” he says. “But I don’t think it’s nostalgia. I mean, I never even saw people using horses to work a farm when I was a kid, so I’m not nostalgic for it. It’s something else.”

As a kid, Schroeder helped out on his family’s farm–a large, modern business full of tractors and pesticides and chemicals. As he got older, he traveled to the Iowa farm during summers to help his uncle run it. On especially busy days, his grandfather would pitch in as well. But usually it was just Schroeder and his uncle, working all 800 acres. These days, Schroeder sometimes works from sunup to sundown farming his 3-acre plot. He considers this progress.

“Well, this tastes better and it’s healthier,” he says, commenting on his organic produce. “But this was really a lifestyle decision. Here, it’s not about controlling nature; it’s about developing a relationship with it. You’re always taking in information and thinking and experimenting and learning. And at the end of the day, you can feel good about what you’re doing.”

Schroeder says that from an early age he knew he liked farming, but he didn’t feel comfortable with the paradigm of the large, commercial farm. He became interested in organic agriculture and went to UC Santa Cruz as an agro-ecology major. One day in class, a student hitched up a donkey to help move some of the heavier objects in the field, “and I just had this vision that I would someday work with horses that way,” Schroeder says. “I almost don’t want to say that, it sounds so strange. But that’s what it was–a vision.”

After graduating, Schroeder and a couple of friends bought horses and rode them for four months along the Pacific Coast Trail to Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon. From there they hitched a ride to northern Idaho where they had already scoped out a place to live.

Schroeder spent the next couple years farming with his horse there. During the winters, a friend would snowshoe over to his cabin, carrying a guitar on his back, and the two would play music and sing all day. When a popular reggae band lost their drummer, the members asked Schroeder to play with them. He sold his horse and toured with the band through the Western states, but eventually he quit and moved back to California. He still plays, though, and has been with the local reggae band Biocentrics for the past decade.

After a few years back in California, Schroeder got a job with a wildlife biologist. That’s where he met Cadman. “I wasn’t looking to get married, but when I met her, everything just fell into place,” he says with a smile. “And then we had Rosalie–and that’s been incredible.” But along with the love for a child comes the worry over what kind of world we’re handing over to all children. “We’ve got to make some changes,” Schroeder says. “We need to think about what progress actually means.”

Like his wife, when Schroeder speaks about the environment, he doesn’t sound angry or condescending. The two seem to have found a balance between being concerned for the world and enjoying the world and their lives, right here, right now.

“Oh sure, sometimes I think the world’s going to hell in a hand basket,” says Cadman with a laugh. A biologist who works part time for the city of Santa Rosa as a natural resources specialist, Cadman also teaches biology at Santa Rosa Junior College. “But thinking that way doesn’t really help anything. Besides, who wants to be upset all the time. You can strive to make a difference and enjoy your life all at the same time.”

For Cadman, that joy comes from watching a tree blossom in the springtime, she says. It comes from eating dried fruits in the winter, made from the summer harvest. And for Schroeder, joy includes working with Sparky and Ike.

From how he describes it, farming with horses sounds like an intricate dance between man and nature. Perhaps it’s the way a surfer feels, riding a wave, or a skier flying down a snowcapped mountain. There’s that state you get to, where everything flows and the experience becomes Zen-like.

There’s such an appeal to watching that flow that some people have started hiring Schroeder to plow and mow their land instead of renting a tractor. “It takes about the same amount of time with the horses as it does with a tractor and the cost is comparable, but the horses are a lot quieter,” Schroeder says. “Plus, people tell me they really like watching the work. There’s just something very soothing about the whole process.”

Schroeder and his horses also work at weddings and other celebrations. But instead of pulling the usual plows behind them, Sparky and Ike pull a white coach with red velvet interior.

“I used [the coach] on Mother’s Day,” Schroeder says. “I took Denise and Rosalie out for a ride. It was beautiful outside. I had my family with me, the horses were pulling us. It was perfect.”

Produce from Stone Horse Farm is available at the Sebastopol Farmers’ Market, Sundays 10am-1pm. Stone Horse is also a member of Farm Trails. 5743 Occidental Rd. 707.576.7237.

From the July 25-31, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.