FOLLOW US

Birds of Wrath

Jim Tigan’s SUV is an aviary on wheels. When he opens the cargo door, an enormous Eurasian eagle-owl swivels its head to stare back with gleaming orange eyes. Perched comfortably in their respective cubicles, two falcons appear unfazed—they’re wearing little leather hoods that block their vision. When Tigan uncovers Beebe, an 8-year-old saker falcon, she hardly blinks before scanning her surroundings. After he gives the signal, she is nearly out of sight within seconds, taking an inventory of the area’s thermals for future reference and, most importantly, striking fear in the tiny hearts of starlings.

Marauding birds can inflict heavy damage on vineyards, especially flocking birds like starlings, and especially in the Carneros area. Deterrents such as shiny tape and gas cannons may have limited effect and it’s labor-intensive to apply miles of nets. For the past two years, Ram’s Gate has retained the bird abatement services of Tigan’s Tactical Avian Predators. As the owl waits in the car for his moment in Pebble Beach (seagulls are his specialty) the certified master falconer and his assistant, Bo, spend the day running after their birds. Tagged with radio transmitters, the falcons are free to roam, but they do their job, whatever it is: Beebe recently did a stint on a reality TV show, delivering a wedding ring.

Tigan gets Beebe’s attention by whistling, and brings her back in by swinging a tasseled lure—like a dog chew toy—over his head. In a flash, the falcon nails the lure and gets her reward—bits of restaurant-grade quail meat. Tigan’s falcons generally don’t attack the starlings; they only need to haze the birds and inspire them to move on to someone else’s vineyard.

It’s an elegant way to protect grapes, if not the most inexpensive. But plastic nets eventually become waste, and they’re a hazard to native songbirds and raptors, Tigan says. Part of the upside of Tigan’s falconry service is that he brings his birds into the winery at the end of the day, where they’re a big hit with visitors.

There’s still plenty to peck on at Ram’s Gate, but they’ve changed up the program since we stopped by in 2011. The à la carte small plate menu didn’t work out—not that it wasn’t popular. Now, the capacious, upscale barn-styled joint offers a tray of small bites with guided wine pairings, a gab-with-the-chef rendezvous, as well as tastings at the bar. Top pick: 2012 Ulises Valdez Diablo Vineyard Grenache. When the dust settles on spicy-earthy notes, sweet cherry licorice is revealed, and the fruit lingers under top-palate dryness.

Ram’s Gate Winery, 28700 Arnold Drive, Sonoma. By appointment Thursday–Monday, 10am–6pm. Tasting fees from $20. 707.721.8700.

Sons & Mothers

[image 1]

It’s been a long road for Justin Townes Earle. The son of country star Steve Earle and godson of legendary songwriter Townes Van Zandt was raised almost solely by his mother, Carole Ann Hunter, from the time he was 2 years old.

It’s this rocky past that informs Earle on his latest album, Single Mothers, released Sept. 9 on indie rock label Vagrant Records. Certainly, the alternative folk sound that Earle has matured into over his career has been influenced as much by his personal history as his musical lineage. He was once considered a bad boy of country, with physical altercations and drug abuse creating obstacles to his artistic output. Now, Earle is determined to put the past where it belongs. He recently moved to New York City, got married, sobered up and began to mend those old wounds on his new record.

Single Mothers is a focused collection of contemporary tunes within the context of classic folk. The songwriter is at the top of his game here, with a soulful and patient delivery that transforms simple pedal steels and brushed snare drums into sonorous and plaintive moments of melodic perfection. This week, Earle brings his new batch of songs with openers American Aquarium when he plays Napa.

Justin Townes Earle performs on Sunday, Oct. 5, at City Winery, 1030 Main St, Napa. 8pm. $30-$45. 707.260.1600 —Charlie Swanson

Raise a Glass

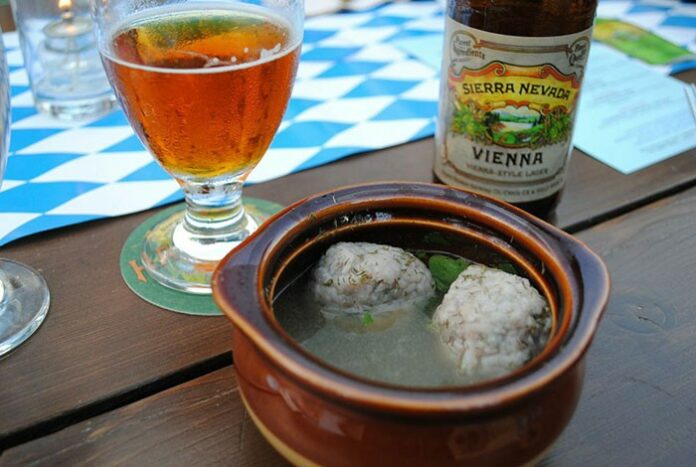

Oktoberfest came to HopMonk Sebastopol last weekend.

The brewpub, which also has locations in Novato and Sonoma, hosted the latest in a series of beer-maker dinners aimed at elevating brew’s place in fine dining. This time, HopMonk’s Dean Biersch and Kim Schubert invited Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. to collaborate on an Oktoberfest-themed beer dinner.

Guests were met with a glass of the brewery’s well-known pale ale and bite-size schnitzel to whet their appetites for the six-course meal and beer pairing to follow. Each course was punctuated with a breakdown of the food and beer from the experts on hand.

Ryan Tovey and Christian Griffith of Sierra Nevada’s Torpedo Room in Berkeley led what can only be described as beer history lessons, of both Sierra Nevada and their seasonal brews, and the story of beer in general. Guest involvement was encouraged and the result was spirited discussion on everything from the rise of the Vienna-style lager in Mexico to the origination of Russian imperial stout. For beer lovers the dinner offered a wealth of information served alongside the food and beer.

Although the focus of the evening was the beer, the food pairings were perhaps the most exciting. HopMonk chef Billy Reid presented his vision to complement and incorporate each beer into the corresponding food course. Preparation began weeks ago as Reid’s team discussed each beer’s flavor profile and tried to build the menu around the Oktoberfest theme. One result was a grilled bratwurst sausage with Sierra’s Oktoberfest beer inside the sausage and braised in it, served with spaetzle, cabbage and apples. Even the potato dumplings with sweet walnuts and dill featured Vienna lager in its broth.

The entree was traditional sauerbraten served with red potatoes and Brussels sprouts kraut alongside the Harvest IPA. Two dessert courses rounded out the meal: Flipside Red IPA with a caramel- and chocolate-covered soft salted pretzel, with Narwhal Imperial Stout served last with German chocolate cake truffles on skewers.

So why would an event featuring well-known Sierra Nevada Brewing be thrown on such a small scale? Tovey, the Torpedo Room’s manager, says their goal is to stay true to their roots and to “tell the story of craft beer.” The fact that HopMonk is a hub for lovers of craft beer makes it the perfect locale to feature the next level of beer appreciation, and pair it with delicious Sonoma County cuisine.

Sierra Nevada’s success dates back to the first days of the microbrew revolution and is attributed to their grassroots approach to marketing and of course their flagship pale ale. A 1982 article in the San Francisco Chronicle about the brewery helped give the brewery an initial boost. They strive to preserve their grassroots method, and have a great time, as demonstrated by events such as these small-scale beer dinners.

If you missed last weekend’s event others are on the way. Look for beermaker dinners featuring San Diego’s famed Stone Brewing, Lagunitas, and Anchor Brewing, the brewery that started the whole microbrew revolution back in the 1970s. The dinners cost about $65.

Yes Means Yes

Gov. Jerry Brown obviously hasn’t been watching Fox News or reading Forbes.com to hone his talking points on campus rape. On Monday Brown signed the nation’s first so-called “yes means yes” law, designed to address the crisis of sexual abuse of women on college campuses. The rule is designed to ensure that allegations of sexual assault are properly investigated—and that the fellas are clear on what consent is, and isn’t.

“Yes means Yes” flips the script on “No means No,” by putting consent in the affirmative—and offering hints for dudes on what that might mean. The new rule says that in the absence of “an affirmative, conscious and voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity,” you’re a rapist.

Last week, Sonoma State University joined the 22 other state colleges that pledged to hire confidential sexual assault victims’ advocates by next June. The California State University system supported the bill, which was introduced by Assemblyman Kevin deLeon, a Los Angeles Democrat. “This bill is really going to help clarify some of the ambiguities on sexual assault on campus,” says Susan Kashask, chief communications officer at SSU. “What comes next is helping educate the campus on this change. It’s a huge change, and it has to be communicated to everyone—the students, faculty and staff.”

The bill’s gotten national attention and its signing comes as the nation has been fouled by numerous right-wing dunderheads scrambling for a blame-the-victim card to play when it comes to campus rape.

In just the past few weeks, we’ve seen some appalling garbage in the right-wing press that stands up for the unfortunate duty of a man to rape a woman if the woman happened to wander wasted into a frat house.

A Forbes columnist wrote a detestable—and quickly removed—online column two weeks ago that claimed drunk women were ruining frats by forcing men to rape them, a meme amplified on, where else, Fox News’ “The Five.”

The hosts there echoed the Forbes column, defended the writer, and bloviated mightily on the two-way street of personal responsibility.

The Department of Justice in 2007 found that one in five women say they’ve been the victim of rape or attempted sexual assault while in college.

Fair Housing Fight

A few weeks ago we reported on a housing discrimination lawsuit targeted at the Bank of America and its treatment of foreclosed houses. Now Vallejo has been officially added to the ongoing lawsuit, first filed in 2012 by the National Fair Housing Alliance. The lawsuit charges that Bank of America had blown off the maintenance of houses they’d foreclosed on, mostly in black and Latino neighborhoods.

Vallejo was added to the suit based on evidence of foreclosure discrimination by Bank of America. The NFHA and Fair Housing of Marin hit the bank for its poor showing “in the upkeep of its foreclosures in neighborhoods of color.”

The lawsuit implores the federal Department of Urban Affairs to put some federal stink-eye on the bank. So far HUD has hummed a tune of silent nothingness. —Tom Gogola

Peaceful Offering at McEvoy Ranch

The olive branch isn’t anywhere to be seen extending along the wearisome border between the psychotic and the insane in the Middle East—but if you’re up for a peaceful seasonal supper at the Marin-Sonoma border—yes, it’s the McEvoy Ranch’s Wine + Red Piano dinner.

The ranch, located off Petaluma-Platform Road—look for the big white windmill—is famous for its olive oil. The Olio Nuovo, for instance, is a perennially worshipped small-batch product released in the fall.

The family operation is also known for a sustainability ethic that’s been on display since the ranch opened in 1990. The sheep mow the lawns here. It’s like that.

The olive oil is not, however, the star of this show. The event celebrates another McEvoy product: The release of its 2011 proprietary red wine blend, Red Piano.

That wine, and others from the estate, will be “paired,” so to speak, with renowned Bay Area pianist and music writer Sarah Cahill. Apropos of the olive branch, and extensions thereof, Cahill in 2008-09 created two projects, called Sweeter Music and Notes on the War: The Piano Protests. Numerous composers (from Yoko Ono to Terry Riley to the Residents) offered compositions to her that hewed to a theme of peace.

It’ll be a peaceful and delicious good time. The McEvoys promise a dinner drawn from locally produced goodness—and consider these sorts of source materials from the ranch’s organic garden: dino kale, cilantro, fennel and dill—and numerous varieties of beans: true red cranberry, scarlet runner, black turtle and Hidatsa shield.

McEvoy Ranch Wine + Red Piano, Sat, Oct. 4 5-8pm. $150. Tix available online, www.mcevoyranch.com —Tom Gogola

Checking the Check Cashers

State Sen. Noreen Evans says that in her 10 years as a Sacramento lawmaker, “the biggest part of what I have done is to kill bad bills.”

There have been a lot of them.

But one stands as a sort of benchmark for Evans, whose 2nd District seat comprises much of the North Bay: Assembly Bill 1158 from 2011, which would have lifted a $300 state cap on individual “payday loans”—one of few restrictions placed on a financial-services lobby that holds sway among Sacramento lawmakers.

The bill from retired Assemblyman Charles Calderon (D-Los Angeles), would have let an individual borrow up to $1,000 against a future paycheck, in an attempt to expand small-dollar loan opportunities for people of limited means—while also pleasing a lobby that’s poured more than $16,000 into Calderon’s campaigns.

The fight over 1158, Evans says, was “basically hand to hand combat. I killed it several times,” she says, before the bill was finally brought to heel in the Senate judiciary committee.

That fight was emblematic. California is one of 32 states that have allowed the proliferation of payday lenders over the past two decades. Others, like New York, have had longstanding bans on the controversial lending practice.

Payday lenders are a popular borrowing option for people of lesser means without access to credit. And the deal looks good, at least on paper: The lenders offer small-dollar loans meant to be paid off in weeks, for a fee ($15 for every $100 loaned under California law).

But the repayment often drags out for months, and the loans are frequently re-upped as soon as they’re paid off. And then there’s the small print: Outsized service charges and interest-rate spikes along they way, if the borrower happens to miss a payment.

The state has struggled to enact any limits on payday lenders beyond what’s already on the books, says Evans. Since payday lending became legal in California in 1996, the industry has been on hand at every turn to stymie reform, and has relentlessly called for greater lending limits than allowed under California law.

It’s a stalemate, and state efforts to reform the industry have been an “epic fail,” says Liana Molina, an organizer on payday reform with the California Reinvestment Coalition.

One problem: Compliant politicians whose pockets have been lined with payday-loan cash.

Online records show that Calderon is among the top ten recipients of payday lender campaign contributions. He accepted $16,100 from the industry between 2009 and 2012, according to data assembled by the watchdogs at Maplight.org.

There are hundreds of payday lenders spread around the state, with high concentrations in urban areas with significant Latino populations.

The low-dollar lenders are also online, an unregulated market described as the “Wild West of the Internet” by Evans, where there are underwriting regulations or limits of up to $1,000—and late fees and fines deducted from your checking account if you miss a payment.

Even the most seemingly common-sense-level reforms have failed in Sacramento. For example, the state says you can’t borrow money off a future paycheck more than once at a given payday lender.

What it doesn’t say is that you can’t just go to another payday lender and get another loan. And another. And another.

“There is widespread recognition that this financial product can create problems for consumers, especially those living paycheck to paycheck,” says Molina.

“Folks that are willing to talk about the payday lender will often say, ‘I love the payday lender, I love that they are here, I got what I came for, I got what I needed,” she adds. “But there’s a hate relationship when they are in that cycle, because it is hard to get out of it. That’s when they say things like: ‘I wish I had more time to pay it off. I wish it cost less.'”

“There is a legitimate need for small dollar loans and small-dollar credit,” Molina argues, “but the payday model doesn’t meet the consumers’ need. It is debt slavery.”

Molina shares the experience of a Californian named Michael, whose dalliance with payday loans shows how a product advertised as a short-term emergency infusion can create financial havoc.

Michael is on disability and gets government checks every month. He was getting advances on his government checks from a half-dozen payday lenders on each check by the time he met with Molina’s organization, about six months ago.

He was living on a meager income from Social Security and disability, about $12,000 a year, and every month would have to get on a bus to pay off his six payday lenders. “It was his day of personal hell,” Molina says.

[image 2]

Payday Politics

In spite of her opposition to its “predatory lending” practices, Sen. Evans also received campaign funds from payday lenders in recent years.

“I am generally known as not supportive of the industry,” Evans says. “I have not been their favorite person for quite a while.”

In the past several years, she says, “I have really taken on the payday lending industry.”

Records at Maplight.org, an online site that tracks money’s influence on politics—and which uses data compiled by the National Institute on Money in State Politics—show that Evans accepted $7,500 from the industry between 2008 and 2012.

Each of the contributors has set up shop in her district. The contributions include:

The Ohio-based Check ‘n Go donated $3,000 to Evans in separate contributions made in 2008 and 2010. They’ve got a brick-and- mortar operation in Santa Rosa.

Advance America Check Advance, based in South Carolina, donated $1,000 to Evans in 2011. They’ve set up shop in Santa Rosa and around the state.

Check into Cash of California, based in Tennessee, donated $3,500 to Evans between 2008 and 2012. They’ve got outlets in Windsor and Petaluma.

Evans says her constituents expect her to raise money for her campaigns—but also expect that she’ll put the public interest before those of her corporate contributors. She’s adamant that she has done just that—even if there was a learning curve, of sorts, on the payday loan issue.

“I definitely did learn a lot more about the payday lending industry,” Evans says, “and there came a time in 2011, [when] the industry made a big push to expand predatory lending practices.”

“I have also taken contributions from banks,” she notes, “but I also wrote the Homeowners Bill of Rights.”

Molina cautions against looking too closely at contributions as a bellwether of support for the industry.

“Money in politics is a big issue beyond payday lenders,” she says. “If everyone is taking money, yeah, they should stop. But, it’s more about how are you protecting your constituents from egregious financial predatory entities?”

The state as a whole, she says, has failed when it comes to meaningful payday-loan reform.

The situation the hapless Michael found himself in would seem a problem in search of an easy fix: A regulation that says you can only take out one loan of up to $300 per paycheck.

“We tried for years to get that to happen,” Evans says. “We tried to set up a comprehensive database so that the state could track where they get these payday loans, but there isn’t any support in the legislature.”

The North Bay has payday lenders all over the map—in Rohnert Park, San Rafael, and other operators in Santa Rosa beyond those mentioned above. Wells Fargo and U.S. Bank are also in the payday-loan business.

The North Bay is well-represented by various payday lenders, but San Diego, Sacramento, Fresno and Los Angeles, according to the California Reinvestment Coalition, “have the highest numbers of payday lenders in the state.”

Many operate as a multi-function financial services center for poor and marginal folks, people who don’t have bank accounts, undocumented immigrant workers and others.

Some municipalities have taken steps through zoning to rein in or otherwise “shame-zone” their payday lenders.

In San Francisco, for example, payday lenders are described as “fringe financial services” and the city limits areas where they can set up shop.

In Windsor, lawmakers reined in the industry, symbolically, through zoning regulations designed to cluster other sorts of “non-Shoppe” businesses—pawnshops, tattoo parlors—into one area with the lenders, out of view of the monied class.

The California Reinvestment Coalition was among a group of advocacy groups from around the country that fielded a 2013 report on the payday loan industry. It notes that the industry’s predation on the poor has played out on geographic lines.

The report identifies “a regional divide among legislators, with San Francisco Bay Area and northern California members more often voting in support of proposals to rein in the payday loan industry, and those from the greater Los Angeles region siding with the trade associations and payday loan corporations.”

That plays out in campaign contributions: The top recipients generally represent areas where the payday industry has proliferated.

The basic set of rules for payday lenders is that the fee paid to the lender is capped at $15 per $100 lent, and the borrower is typically give two weeks—until the next paycheck—to pay back the loan.

The rules feed a convenient myth that the loans are usually used for short-term emergencies. Many people don’t pay the loan back in two weeks, Molina says.

“They are advertised as for a short-term emergency, but that is very, very far from the actual truth,” Molina says.

“People get into a cycle, and there’s pretty solid evidence at this point that people take out 8 to 10 loans in a cycle, and that’s because if you don’t have the money today for necessities or medical bills, it’s very unlikely you will have the money in two weeks,” she says.

The payday lender is also first-up for getting paid when the paycheck hits, which creates a downward spiral for borrowers who find that they have to pay off the lender before the landlord.

The lender will either have a post-dated check on hand, or, more typically, will have access to the borrower’s checking account.

“They are going to get paid first,” says Molina, “before the rent or anyone else.”

At that point, the debt-multiplier sets in: The payday lender got paid, but the landlord didn’t. Now what?

All too often, says Molina, it means another loan from another payday lender, as in Michael’s case.

Or, borrowers are increasingly going online to an emergent online industry that’s emerged with looser lending limits.

Those lenders have been getting a looking over from the U.S. Department of Justice, but Evans says not to expect much of it.

Later this year, the Federal Consumer Protection Board is expected to issue new proposed guidelines for the payday-loan industry, subject to congressional approval.

“I think it would be nice,” Evans says. “I’m not holding my breath, though, because nothing productive comes out of this Congress.”

Molina hopes new federal rules will kick-start meaningful reform in California, which, she says, should start with limits on a now-unregulated annual percentage rate (APR), which can double or triple a loan in short order (and which kick in if you’ve missed a payment).

Even as it fails on the payday-loan front, the state has made strides to open credit to those of lesser means and lower credit ratings.

Those efforts come from some of the same lawmakers who have accepted thousands from the payday industry lobby in recent years.

For example, according to online records, Sen. Lou Correa (D-Santa Ana), is 10th on the list of state Senate recipients of payday lender cash in recent years ($14,700) but he’s also author of the latest in a series of bills from the last few legislative sessions designed to make it easier for people to borrow—especially in the range between $300 and $2,500.

That range is a black hole for borrowers of limited means. In short: California’s underwriting rules make loans in that range unappealing to banks or other licensed lenders—especially if the borrower is of limited means or has a sketchy credit report.

“A lot of the banking institutions don’t want to provide the short-term loans,” says Evans. Under Correa’s bill, non-profits can now underwrite loans in that range.

In an email, Correa says his law “provides needed flexibility to non-profits that are offering a bridge to Californians whose incomes or credit scores have limited their access to affordable financial products.”

For customers who now rely on payday lenders, the new Correa law might be of some help—even if there’s no payday lender reform in it, or anywhere on the legislative horizon for that matter.

“It’s been a long struggle just to maintain the current protections,” says Evans.

Rent Vent

Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill Tuesday that could set the stage for the future of affordable housing in Marin County—a hot-button issue that has unfolded in recent months as the state reviews a county master plan whose housing provisions have roiled Marin in recent months.

“Affordable housing” is an oxymoron in Marin County. Rents have gone up by 13 percent on average in recent years, according to the master plan, as demand for housing drifts northward from the sky-high rental scene in San Francisco to the suburban enclaves over the bridge. Between 2011 and 2012 the average monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Marin jumped from $1,777 to $2,014.

“Suburban” is the key word: The bill signed by Brown renders Marin a suburban area—no longer officially part of the greater urban sprawl of San Francisco.

The new designation translates into a mandate for fewer affordable housing units than if the urban tag had remained.

Meanwhile, the county master plan, now being reviewed by the state, includes suggestions to deal with Marin’s rents, and includes the possibility of “rent control,” two words no landlord ever wants to hear.

The rent spike means low- and middle-income workers in Marin are having a tough time in their search for an affordable place to live close to the job. Not helping matters: A small but vocal cohort of county residents has steered the debate into rough and ugly waters.

“One of thing that’s become very apparent in the past few years is that there is such a fear of affordable housing,” says Caroline Peattie, executive director of Fair Housing of Marin. “There are some very vocal people in the community who have done quite an amazing job of fear-mongering.”

Peattie cites a barrage of online comments that followed stories in the Marin Independent-Journal about affordable housing—”anonymous, hateful stuff”—as well as comments made in public forums about the master plan.

Proponents share some of the burden of excessive biliousness she says, noting that the housing squabble has been reduced to two raw sides of red meat: “People who are anti-affordable housing are labeled ‘racists,’ and people who are for affordable housing are all about ‘social engineering.'”

The bill signed by Brown this week was sponsored by Marin state Assemblyman Marc Levine and supported by the Marin County Board of Supervisors.

The former “urban” designation came via the U.S. Census Bureau, which sets a so-called density formula for affordable housing to which the county must abide. Sonoma County, a suburban area, must create 20 units of affordable housing for every acre that’s developed. In rural areas, it’s 15 units per acre. For urban areas, it’s 30.

Because of the census designation, “we have the 30-unit acre default,” says Leelee Thomas, principal planner in the Marin County Community Development Agency. “The big concern with the community is that it’s not consistent with [its] more suburban character.”

“I don’t think that most of Marin sees itself as an urban community,” says Peattie, citing the county’s rampant wealth and pale skin tones.

The county is 3 percent black and about 16 percent Latino, she notes—and many residents, she says are more concerned about the “sense of privilege that we have in Marin County: One family where each parent has a car, the kids have a car.”

She suggests those residents spend more time grappling with the needs of other socio-economic groups in their midst.

“I see how really whipped up the emotions get,” says Peattie, “where people seem to feel that the actual fabric of their existence is being threatened by the possibility of affordable housing in their neighborhood.”

“There’s not a lot of middle ground,” she adds, noting that former Marin supervisor Susan Adams was “booed out of office” over her support for affordable housing. Another, Judith Arnold, “almost lost her seat” for the same thing.

Given the jobs boom in San Francisco, says Thomas, “Marin is being looked at as a more affordable place to live than in the City,” she says.

The county’s master plan, she stresses, offers recommendations, not mandates, on the way forward.

The master plan examined housing needs—and the various constraints, challenges and barriers to affordable housing, says Thomas. “There’s no mandate for rent control,” she says. “But we will consider it and look at it. The board has not weighed in on it.”

The plan is being reviewed by the state Housing and Community Development Agency. The county Planning Commission will next have a look, and then the Board of Supervisors will vote on it. Then the plan heads back to the state for certification, Thomas says.

Peattie notes that the suburban designation will create an affordable-housing problem all its own: “The fewer units you build, the more difficult it is to manage economically,” she says. “It’s almost impossible to build affordable housing when you are building fewer and fewer units.”

Say No to Prop 1

North Bay voters: we must reject Proposition 1, the water bond on the November ballot. This sham would burden us with $7.5 billion in new debt, which translates to $14.4 billion including interest. That’s $360 million per year for 40 years that could be used for other priorities like education and health care. For an investment like that, we have a right to expect relief from immediate drought stress and solutions to our long-term water crisis. Prop 1 fails to fulfill these critical needs.

Prop 1 was negotiated for weeks behind closed doors with little opportunity for public input. In the end, Republican legislators played hardball, refusing to support the package unless it guaranteed $2.7 billion for water storage, read: new dams.

That’s a waste of money. Raising the Shasta Dam and building the Temperance Flat Dam on the San Joaquin River and Sites Reservoir in the Sacramento River watershed could increase the state’s water supply by only 1 percent (316,000 acre-feet), a drop in the bucket that wouldn’t be available for the years or decades it would take to build these dams. And, this trickle would not benefit the North Bay: it’s the dream of corporate agriculture interests in the west and central San Joaquin Valley who want to keep growing water-intensive crops on toxic soil to export to emerging markets like China.

What’s more, Wes Chesbro, our veteran environmental legislator on the North Coast, cast his vote against the bond in the legislature, citing potential diversions from local rivers that could hurt salmon recovery efforts.

A real water solution for California must focus on conservation, stormwater capture, and groundwater cleanup. Reports by Natural Resources Defense Council estimate that California could easily gain 5 to 7 million acre-feet of water through these methods. Another 500,000 acre-feet could be saved in major cities by fixing leaky pipes. But, Prop 1 dedicates only $100 million for water conservation and $200 million for stormwater projects—and forces taxpayers to pay for useless dam projects in order to access this woefully inadequate funding.

Reject Prop 1 and demand real water solutions.

Denny Rosatti is executive director of Sonoma County Conservation Action and Sandra Lupien is communications manager of Food & Water Watch.

Last Days

The saga of ruin and futility is painful enough for Americans to remember. The finale is even more humiliating, and that explains the sometimes tiptoe approach documentary maker Rory Kennedy (RFK’s daughter) takes in Last Days in Vietnam.

The primarily American interviewees here include the ever-exculpatory Henry Kissinger, secretary of state during the end of the war in 1975, former CIA agent Frank Snepp (the sharpest character among these analysts) and Juan Valdez and Mike Sullivan, two of the last 11 Marines airlifted off the roof of the American embassy in Saigon. Kennedy also found several officers from the USS Kirk—the vessel whose sailors deep-sixed the empty Huey helicopters into the South China Sea, in famous news photos.

The first half, in shadowy libraryish lighting, is a bit too laden with talking heads for the large screen. Stick with it, because the later story of the evacuation of Saigon is far more thrilling, and saddening. The one who isn’t there to defend his actions gets the most blame: Ambassador Graham Martin’s deliberate unwillingness to see what was coming was fatal for an untold number of our South Vietnamese allies. Martin’s hesitation meant that the U.S. had to use the worst option for removing tens of thousands of refugees—a short-notice, all-night airlift by slow, small helicopters—a military operation that was like draining a pond with a teaspoon.

Warm stories of courage enliven the second half of Last Days, amid the surreal incidents of the implosion of the Embassy (we learn it took two Marines eight hours to burn one million dollars in U.S. currency). Stay for Miki Nguyen’s incredible account of the escape of his entire family, thanks to his nerveless pilot father and a borrowed Chinook helicopter.

The finale is comfortless, with footage of ARVN soldiers leaving their boots and uniforms and melting into the crowd. But the savage vindictiveness of the victorious forces were everything that the commie haters dreamed of, and more.

Last Days in Vietnam opens Oct 3 at the Rialto Cinemas, 6869 McKinley St, Sebastopol. 707.539.5771.