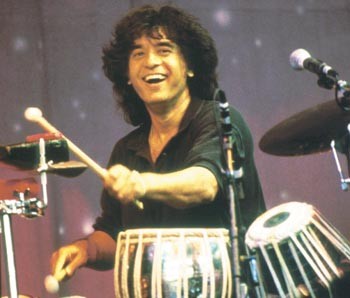

The world at his fingertips: Marin County percussionist Zakir Hussain has a career that ranges from touring with jazz fusionist John McLaughlin to performing classical concerts in his own homeland of India.

King of Rhythm

Zakir Hussain taps a world of sound

By Greg Cahill

“IN INDIA, we were always taught that we’d been playing music for the past 5,000 years, so we arrived in this country thinking, “We’re the ones whom people should learn from. We never thought of ourselves as people who should also be learning from others,” says Zakir Hussain, 50, a world-class tabla player and San Anselmo resident. “That’s why it was so great to go to the University of Washington in Seattle [on his first trip to the States in 1969] to teach because I came in contact with all these great masters of African, Middle Eastern, and Indonesian music who also taught at the school’s ethnomusicology department.

“It just opened my eyes that we in India have to keep learning to expand further, and we can’t do that without opening up to the world of sounds around us.”

He’s learned that lesson well. Hussain–an energetic fireball with lightning-fast hands, boyish good looks, deep-set brown eyes, and charm galore–still spends at least six months each year performing classical North Indian music in his native land and throughout the world while releasing top Indian classical acts on his own Moment! record label. But he also has earned a reputation in the West as a savvy fusionist and “the hottest crossover figure to emerge from India since Ravi Shankar jammed with the Beatles,” as one enthusiastic music writer once opined.

Since his 1969 U.S. concert debut at the Fillmore East in New York (replacing his father, the late Indian tabla master Ustad Allah Rakha, as accompanist for sitarist Shankar), Hussain has racked up an impressive list of credits, playing with Grateful Dead percussionist Mickey Hart (the two shared a 1992 Grammy Award for the evocative Planet Drum CD), jazz fusion guitarist and longtime collaborator John McLaughlin (with whom he performs as part of the acoustic-based group Shakti), jazz saxophonist Joe Henderson, rocker Van Morrison, and dozens of others.

Most recently, Hussain recorded Saturday Night in Bombay (Verve), a newly released reunion album with Shakti, featuring McLaughlin and a cast of other Indian musical heavyweights. Earlier this month, Hussain–who performs a rare North Bay concert Aug. 25 at the Marin Center with sarode master Ali Akbar Khan–wrapped up a whirlwind world tour with Shakti, breezed into town for a pair of San Francisco shows with Tabla Beat Science–producer/bassist Bill Laswell’s eclectic all-star world-beat ensemble–and even managed a couple of well-deserved days off before jetting to Japan for a show with the acclaimed Kodo taiko drummers.

“It is a dizzying schedule,” he admits. “It’s quite a lot of different things, and that is what is exciting about my life at this moment. I’m getting so many different venues to explore. I feel lucky that all this has come my way.”

THAT’S A BIT of an understatement. Hussain–who himself was the subject of a recent documentary film screened at the Mill Valley Film Festival–just finished recording the soundtrack for the latest Merchant-Ivory production, The Mystic Masseur, which will take him next week to the film’s premiere at the 2001 Telluride Film Festival in Colorado; he’s completed recent scores for the Alvin Ailey Dance Company and Lines Contemporary Ballet, and is now composing a new dance piece for New York choreographer Mark Morris that will team up Hussain in April with classical cellist Yo-Yo Ma; he’s preparing for a North American tour next month with the phenomenal L. Shankar, the Indian 10-string double-violin player; and, in November, Hussain returns to his native homeland for another series of classical Indian concerts.

“I don’t consciously go out and look for all these different projects,” Hussain explains modestly, “but people call me up and ask if I’m interested. And, of course, I am. To some extent, it all got started when I did a solo performance for Alonzo King’s dance company in San Francisco–a piece called, ‘Who Dressed You like a Foreigner?’ It got rave reviews and moved to New York, Boston, and other places. That sort of opened the door for some of these other venues.”

Of course, Hussain is no stranger to film scores. In 1976, he collaborated, with Hart, to the soundtracks of the Francis Ford Coppola masterpiece Apocalypse Now (released last week in movie theaters as the expanded Apocalypse Now Redux edition), and later worked on the acclaimed PBS-TV documentary series Vietnam: A Television History. Since then, he’s composed film scores for Ismail Merchant’s film debut In Custody and Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha, as well a several documentaries and Indian films.

“You know, the bug bit then,” he says of the acclaimed Apocalypse Now score. “It’s fun doing film scores.”

YOU COULD SAY that Hussain has led a charmed life, though that would belie the extraordinarily hard work he has put into his art. But he did get started while still in utero. His father started tapping out the complex tabla beats on his then-pregnant wife’s tummy while Hussain was still in the womb. Hussain’s lessons continued into a childhood that was blessed by contact with many of the world’s greatest musicians. At age 13, he met George Harrison, when the famous Beatle first visited India to study sitar with Ravi Shankar–a pivotal event that led to the introduction of Indian classical music to mainstream Western audiences.

In Mickey Hart’s 1998 book Drumming at the edge of Magic: A Journey into the Spirit of Percussion, Hart describes the marathon chillas: a 40-day ritual retreat during which Hussain locked himself away with his instrument, playing night and day with only short breaks to eat and sleep. During one such event, Hussain drove himself so hard that he hallucinated that his drums were ominous beasts.

On his first trip to the States, Hussain hooked up with Hart and formed the Diga Rhythm Band, a vast lineup of percussionists modeled after the gamelan orchestras of Bali.

In the intervening years, whether jamming with the Dead in a west Sonoma County barn or trading licks with McLaughlin at a North Beach rock club a world away from the concert halls of Bombay, Hussain has learned aspects of drumming to which he was never exposed in his homeland. “There is a certain way we play music in India,” he explains. “We tend to lean toward the perfect execution of a phrase–a tal, or complicated rhythmic cycle. But we don’t necessarily pay attention to what the instrument can do in its range of melodic tone. And that’s what I’ve learned by watching Puerto Rican conga players or the African talking drum or the various subtle ways a jazz drummer places the beat on symbols.

“Playing with groups like Shakti has allowed me to look at my instrument from a different point of view and has shown me what more [the] tabla as an instrument can do.”

That doesn’t mean Hussain isn’t still learning from the Indian masters. For instance, he reveres the venerable Ali Akbar Khan, recipient of a MacArthur genius grant and San Anselmo resident whose longtime San Rafael school is the leading Indian music institute of its kind in the United States. “With Khansahib, you are sitting in front of a master, you go for a ride with the master. With someone like Mickey Hart or John McLaughlin, you are more like a friend and you can play with each other, jump on each other’s back, or roll in the field, but with Khansahib, you are in the presence of a musical godhead and you treat your musical experience in that manner.

“You never know what’s going to come at you or what you’re going to learn, but you keep your eyes and ears open and he will provide the kind of inspiration you need to get another musical lesson. It’s an incredible thing.”

Zakir Hussain will perform Aug. 25, at 8 p.m. with Ali Akbar Khan and Sri Alam Khan on Saturday, at the Marin Center, Avenue of the Flags, San Rafael. Tickets are $40 and $25. 415/472-3500.

From the August 16-22, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.