See Change

The Sonoma County Museum dares to dream

By Gretchen Giles

Here’s a dream to start the North Bay cultural community drooling: It’s 2005, and the Sonoma County Museum is revamped and renamed. Maverick architect Michael Maltzan, having successfully shepherded his renovation of the New York Museum of Modern Art’s temporary quarters in Queens way back in 2002, has finished building a 44,000-square-foot multidisciplinary museum space on Santa Rosa’s Seventh Street.

Entering through the refurbished Federalist post office that used to entirely house this formerly forgettable institution, one finds a plethora of exciting choices in fabulous new galleries. Should it first be historian Gaye LeBaron’s permanent “Seven States of Sonoma” exhibit? Look, there’s the Christo and Jeanne-Claude room, where the largest collection of their work in the United States is found.

How about the extensive children’s gallery space, the lecture just commencing in the conference room, a film screening in the theater, or a leisurely chèvre-and-foie-gras-on-spring-greens kind of lunch at the outdoor cafe? Afterwards let’s stroll through Yoko Ono’s conceptual work or gawk at more of Chris Ofili’s elephant dung Madonnas than you could shake an angry Rudy Giuliani at.

James Turrell’s permanent sky space installation lets the blue firmament in magnificently, doesn’t it? And did you hear that Andy Goldsworthy is in residence in Freestone, busily sticking yellow leaves onto green with spit?

San Francisco is suddenly obsolete. Heck, it’s a dream: New York is suddenly obsolete.

While museum directors on either coast are hardly shaking in their Manolo Blahnik’s, much of this dream is actually going to be stone-cold reality in just three short years.

Breathtakingly ambitious, the Sonoma County Museum plans to raise and spend more than $25 million to erect a new block-long building that will shelter a renewed focus on local history, stress the importance of the surrounding environment to our sophisticated rural culture, and showcase traveling shows from the Smithsonian, the Brooklyn Museum, and the MOMA, among others–even perhaps competing with SFMOMA for eyes and feet, hearts and wallets. Aiming to be the most important–nay, the only–art institution of its kind from San Francisco to Portland, the SCM will dramatically ratchet up the level of the North Bay cultural scene.

Factor in the Green Music Center’s exciting musical programs, the new Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center, the continuing innovation of the Sonoma Museum of Visual Art, the far-ranging exhibitions showcased at the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, and SSU’s stellar University Art Gallery, and you can plan on staggering around for most of 2005 in an art-soaked stupor while the children argue heatedly about the relevancy of Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm to a post-postmodern society.

Because if SCM executive director Dr. Natasha Boas has her way, Pollock’s dribble and flick will just be another downtown show for the kids to swing by on their way home from school.

Seated in the cheerful chaos of her upstairs office in the museum’s current headquarters, Boas, a slender 30-ish brunette, is elegantly attired in a dark pantsuit and heavy turquoise choker. Meditatively patting a Smithsonian prospectus for available exhibitions she might one day choose to bring here, she explains in part just why it is that Sonoma County even deserves such a giddy project.

“We’re far enough away from San Francisco so that inner-city kids–kids who don’t have money–cannot go to see an original work of art, say, a Jackson Pollock,” she says. “It’s my hope that we’ll have Jackson Pollocks here. It’s my hope that you will get an Ingres show or to see Picasso’s erotic drawings, and that kids will be able to have access to it. To me, that’s the major reason: the education of the next generation.”

High Art

The building blocks for the next generation have already been firmly laid by Boas’ hiring last September and by the actual-indeed securing of architect Michael Maltzan to revamp the old building and design the new. Boas, who describes herself as a semiotician among “the generation of deconstructionists” who studied under master Jacques Derrida himself (she eventually earned a Ph.D. from Yale University) is, to put it mildly, no academic slouch. She grew up playing with the innovative designers Ray and Charles Eames’ kids in an environment that she describes as a “thoroughly Modernist childhood.”

Raised in San Francisco and France by biliterate parents, Boas maintains that she’s a “Bay Area girl at heart” who visited Geyserville during summer vacations and married in Kenwood. And then of course there’s that “funky ’70s high school” she attended in Rome run by three Harvard professor expatriates, during which time she won art awards and helped to restore the first-century statue of Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. This while others of us were learning to canoe.

The hiring of Los Angeles-based Maltzan is so dizzying that it’s almost comical, like one of those tourist T-shirts that lists international cultural capitals and ends with . . . Santa Rosa? A senior architect with Frank O. Gehry’s firm for eight years, Maltzan is on the Hot List of young architects bound to reshape public buildings in the United States. And we will have one of them. But will it be a big-city-type building plopped down in a small-city-type place?

“Absolutely not,” Boas says, shaking her head. “What’s wonderful about Michael is precisely that his work is not L.A. We had a very serious, rigorous selection committee process, and it took six months. We went through New York architects, local architects–we cast a very wide net.

“[Maltzan] worked for Frank Gehry, but he’s not Frank Gehry; he doesn’t create projects that land in a place. He responds to the place. If you look at his architecture, it’s the specific neighborhood or the specific place. It’s about the use of the old buildings, the existing buildings. The Queens MOMA is specifically first a stapler factory and then a response to what the MOMA is.”

What further causes hand-rubbing delight is that if Maltzan builds it, they will come–the “they” in this instance being all the creamy art goodness shown at other institutions that we’ve always had to cross a bridge or hop a plane to see. But have Maltzan design the floor to ceilings, track the lighting, and plant the grass, and before you know it, Ingres’ nudes, Picasso’s erotics, Ofili’s dung, Yoko’s grapefruit, and Pollock’s Rhythms are knocking down the doors, begging to be shown.

“When I was back in New York for the opening of the Queens MOMA,” Boas says in evident delight, “several of the directors said that since we’re hiring Michael, they’ll send us their shows because our galleries will be so perfect. The architecture is actually going to allow us to get high-level shows because we’ll have the best materials, the best spaces, the best lighting–all of those things. Right now,” she sighs, “we can get very little.”

The Nexus of Multitransparency

Significant changes in any institution rarely happen without someone’s knickers getting into a twist, and Boas has to navigate the concerns of other institutions as well as those who worry that the new SCM will focus less on history, its original mandate.

“We’ve got wonderful art venues here, there’s no doubt about it, but what the county really needs is a nexus,” she says, “an institution that’s large enough and taken seriously enough to collaborate with the smaller institutions to bring about a significant cultural change.”

Gay Dawson, executive director of the Sonoma Museum of Visual Art located at the Luther Burbank Center, is warm but guarded. “It’s exciting to have a more serious program at the SCM and one which will, to some extent, help us all raise the bar of the arts in the county. We collaborated on the Christo show [last fall], which I curated. It remains to be seen how we can effectively work together.

“The interesting thing about SMOVA is that it’s within a 50-acre arts campus,” Dawson stresses, referring to the LBC’s extensive grounds, “and our plans are to develop that campus. The context of the SCM is that it’s downtown and will be redeveloping downtown conditions. I think that we’re far enough away that it’s not redundant.”

The real fear of redundancy may be in finding the funding. With so many area arts organizations scrambling for the same gaggle of checkbooks, a $25 million goal looks to have an awful lot of zeroes.

“We’re cultivating the higher-end donors, introducing the community to our program plan and to our architect,” Boas says crisply. “We have enough money to go through the design stage and to really flesh out that program plan and come up with a master plan and sketches. We’ll start the capital campaign in spring of next year.

“You have to have a major lead gift,” she continues. “We’ve got a state grant of $250,000, and we still have $100,000 of that left. It’s a 36-month plan, and we’re right on target. We do have a lot of money to raise, certainly, but I’m confident that we’ll reach our goal.”

Still in the “silent” phase of funding, which means that Boas won’t comment on who’s been contributing, surely the SCM is begging at the same wallets as those being opened for the Green Music Center, ongoing gifts to SMOVA, the Sebastopol Center for the Arts’ renovation, the new ‘n’ needy Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, and even the egregiously managed Sonoma County Cultural Arts Council. “We need the Green [Music] Center, but we also need a museum,” she stresses shortly.

Thinking back to the beginning of her tenure, Boas says, “When I got a phone call from a headhunter a year ago I thought, ‘Could there be anything more exciting and perfect for me at this time in my career than to try to build a museum that will represent an icon for Northern California–not just Sonoma County, not just the North Bay?’ There will be no museum of this stature to Portland.

“We really are a culture. We’re a subculture in the United States, and we have something to say, we have something to preserve, we have something to perpetuate, and no one has really explored that.”

As for keeping a historical context, Boas is emphatic. “There’s been a lot of conversation in the history community here that this is becoming an art museum, and I keep saying that it’s a comprehensive museum. Like the Oakland Museum, you can see art, but you can also see history. The multitransparency between disciplines is my thing. We’ll always create forums. We’ll have a show and then we’ll have a discussion. We’ll always be linking it to the place, linking it to the history.

“Right now, even with Jack Stuppin’s paintings [see sidebar], we have the apple-blossom vitrine that starts to tell a story, and in the new museum, we’ll be able to tell more stories and flesh it out in those ways. It’s tricky, but those of us who have gone to major museums in the world have seen all of these disciplines coexisting. It’s a normal marriage, and we can do it in many exciting ways. Just [remaining] a history museum will not attract a large enough audience in the next generation. It’s just pragmatics. We don’t have enough content to do it.”

Frankly, the SCM’s never had enough content to do it, which is among the reasons that the sea change at SCM is so amazing to interested onlookers. Frequented mostly by school children and tourists, the SCM is generally ignored by the resident community, just an old building filled with poorly preserved artifacts blurring by on the right while a left turn takes one into the Santa Rosa Plaza parking lot.

Rethinking Regionalism

Boas intends that the blur will now be inside the museum. “We don’t want to be another cookie-cutter kunsthalle [exhibition space] or a museum that you can plop down in Nebraska or Boston or Berlin, because that’s what happened in the ’90s,” she says. “The phenomenon of showing the same art everywhere without regard to where you are is something that I want to resist, especially here in Sonoma [County], because the county has resisted the temptation to become Napa, resisted the urge to lose its identity. I want to start rethinking regionalism.”

Embracing an overarching “Sense of Place” theme to gird the museum’s mission, the SCM plans to salute Sonoma County’s erudite regionalism through an ongoing exploration of the notion “Where Land Meets Art.” Grounded in their permanent ownership of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Running Fence memorabilia, as well as other of the couples’ land-art artifacts, the SCM intends to show in every conceivable way how art and earth comingle.

“It is a laboratory right now,” Boas admits. “We’re working it out. It’s also a niche, as no other museum is focusing on that topic, but it’s also broad enough to remain exciting.”

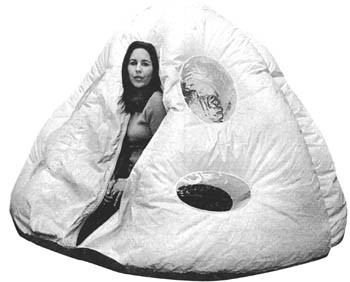

Drawing from the county’s protohippie origins as a catalyst for communes and other intentional communities, the museum kicked off its thematic mission last February with the “Utopia Now! (And Then)” exhibit.

Next up is this fall’s miniretrospective of renowned Bay Area painter Hassel Smith, now in his late 80s and residing in England. Focusing on Smith’s work while living a bucolic life in Sebastopol in the 1950s, these paintings, both abstract and representational, reflect his reaction to the apple-orchard life he led when not teaching at what is now the San Francisco Art Institute, or arguing amicably with Richard Diebenkorn. And perhaps most exciting, internationally respected conceptual artist James Turrell comes to town March 4, 2003.

Turrell may not strike a chord until you cast back to that mysterious guy who purchased an Arizona volcano called the Roden Crater, only to spend all his time and money grading its rim to better contain the shifting light and color of the 24-hour sky from inside its natural vault.

The result is nothing short of stunning; Turrell has literally changed the face of the earth and how the sky is viewed from such a face. The Roden Crater will open to the public next year, and SCM visitors will be able to witness its swathe of firmament via a video feed to be supplied by San Francisco’s Exploratorium.

There is also some discussion that Turrell will be commissioned to permanently produce one of his “sky space” installations for the remodeled museum, a prospect of enormously exciting proportions. “Upstairs,” Boas says, ever ready to rethink regionalism, “we’ll do a show about mapping Sonoma County and start to talk about mapping space and doing a series of workshops for teachers so that we can talk about Turrell in that context.”

As for Andy Goldsworthy, well, this hopeful wisp may not actualize. Goldsworthy may never indeed put saliva to leaf on Tom Golden’s Freestone grounds. But when this property reverts to the SCM, as Golden has promised it will, someone will inevitably lick land as part of an ambitious in-residence project for land artists, the first of its kind in the county.

Boas maintains a measured enthusiasm. She does, after all, have to wait three long years to realize her vision. “We have to build program and staff as we build the museum,” she cautions. “The laboratory is what excites me, bringing in new constituencies. The Jack Stuppin show will bring in one constituency; the “Utopia Now!” show brought in another.

“Hassel is going to put us on the map,” she adds, “connecting the dots with the San Jose Museum and the De Young. James Turrell is going to connect us to many other things. Who comes in the door for each show? Who are we influencing? What educational things can we do for each one? It’s exciting.”

Pinch yourself, because not only is this dream exciting, it’s actually going to come true.

From the September 12-18, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.

© Metro Publishing Inc.