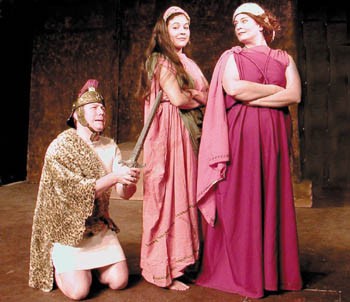

Photograph by Rory McNamara

We Are Family: Ann Martino, shown with foster children Jacob (left) and Matthew, feels that although fostering children has benefited her life, the system needs fixing.

Fostering Change

Is the California foster care system failing its kids?

By Joy Lanzendorfer

When you know a child needs you, it’s hard letting them go when they are adopted or returned to their natural parent,” says foster parent Joan Froess. “But you do it. And it’s so worth it. For most foster parents, it’s hard to stop once you start.”

Froess, who is president of the Redwood Empire Foster Parent Association, usually fosters newborns, an age group she feels drawn to. Most of her children are drug babies, she says, but sometimes they are removed for neglect or abuse.

Being a foster parent has given Froess’ life meaning. After 23 years and 79 foster children, she feels like she’s made a difference.

Ann Martino has also found foster parenting to be enriching. She’s had 15 children from ages two to 18 go through her home over 12 years. She became a foster parent because she wanted to give something back to the community. But it has given back to her as well. The bonds she created with her children have been lasting.

“I have four grandchildren, even though I’ve never given birth or been married,” she says. “When it comes to some former foster kids, I am their mother. And for all intents and purposes, I am the grandmother of their children.”

But even though the two women agree that being a foster parent is one of the best things they’ve ever done, they differ in their opinions on whether the system works. Froess believes that it does and that it benefits the entire family. Martino is less optimistic.

“Does it work?” she says. “To that I have to answer, what is the alternative?”

There’s no doubt the child welfare system has come a long way since Oliver Twist’s time. Horror stories of children being beaten and starved in orphanages have given way to a system where children are removed from abusive situations and, ideally, placed in safe, loving homes where they have every opportunity to thrive as functioning human beings. That’s a pretty good start for a system that deals with one of the most complex relationships human beings can forge–that between a parent and a child.

But most agree there is still room for improvement. There are 97,000 children in California’s $2.2 billion child welfare system. Two recent reports by the federal government and a state watchdog agency take the system to task for failing the children it was put in place to protect.

According to the reports, children are lingering too long in foster care and being jerked from foster home to foster home before any sense of stability can form. Too many children are returned to abusive situations where they are victimized again.

The report doesn’t demonize foster parents like Marino and Froess. Instead it takes aim at the bureaucracy that prevents them from offering foster children the best care possible. According to one of the reports, the child welfare system is leaderless, bureaucratic, and, despite efforts to reform some areas, has made little progress in meeting the children’s needs.

But how true are such scalding criticisms? Should we be worried about our child welfare system? And how is it affecting Sonoma County’s 540 foster children?

The most significant of the two reports, the 87-page California Child and Family Services Review, or CFSR, was put out by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and comes with the threat of an $18.2 million penalty if the California Department of Social Services doesn’t create a plan to fix the problems in the system.

Susan Orr, associate commissioner for the Administration for Children and Families, a division of Health and Human Services, points directly to one of the main oversight failings of the system: “Prior to this review, we’ve just looked at the systems on a process-based level by reviewing rules and regulations and whether the states comply with federal law. The problem with that is that we have never addressed whether or not the children were actually being assisted by child welfare.”

The federal government has reviewed 32 states so far, and none has met more than two of its seven safety and well-being requirements. The government set the bar purposely high so that all states have room to improve. California didn’t meet a single one of the federal requirements and has extra difficulty because its program is so large and its structure–care is handled on the county level and funding on the state and federal level–so complex.

The state acknowledges that it has room to grow.

“The review has provided us with valuable information about what we agree are our priority areas,” says state spokesperson Andrew Roth. “We are working on a program improvement plan due in March that will target these areas.”

But the state is also quick to point out that it did well on many points on the CFSR. Among other things, the federal government noted that California is swift to respond to reports of abuse, provides ample services to families, places children near their relatives, and helps the parent-child relationship while the child is in state care. In addition, California recently won a $17 million award from the federal government for finding homes for hard-to-place children, something not mentioned in the CFSR.

But other areas of the system appear to be lacking. The rate at which children are being revictimized by their abusers raised red flags in the CFSR. Often, the state removes a child from a home–placing the child in foster care–and requires a parent to complete state-mandated requirements, such as drug counseling or anger management. After the parent proves to the state that the home has been improved, the child is usually returned home.

But abuse can still recur. According to the report, 11 percent of children in the state foster system experience a recurrence of abuse within a six-month period, prompting their replacement into foster care. This situation is a double whammy for the children, for not only is the repeated abuse obviously traumatic, but double removal from their parents or guardians can also inflict trauma.

In Sonoma County, 21 children reentered the foster system in 2001, down from 26 children in 2000. But it is difficult to accurately track how many children experience repeat maltreatment, because families can move around and leave the county.

“It does happen,” says Carol Bauer, director of Sonoma County’s Family, Youth, and Children’s Services. “But it’s not due to a failing in the system. Recurrence of abuse is usually due to complex reasons, such as a change in lifestyle or [when] needed services–like anger management–are no longer available to the family in question. Foster care will never solve all those problems. If there’s an expectation that it will, it’s unrealistic.”

The CFSR is also concerned about the rate of abuse in foster care homes, which happens occasionally (about 1 percent of children are abused in their foster homes). Foster parents go through lengthy screening and training before they can take in children, and the compensation is fairly low–approximately $400 to $500 per child per month–so potential abusers are usually screened out. However, one occasionally slips through, though locally the county says it hasn’t seen any abuse in foster homes for a long time.

Another concern introduced by both the CFSR and a report by the independent bipartisan watchdog group Little Hoover Commission, is the length of time children are left in foster care. Ideally, the foster system provides children with care until their home environment becomes safe or until they are adopted.

But according to the Little Hoover Commission, half of children stay in care for six to 36 months and a quarter stay 42 months or longer. The national standard is one year. In addition, many children are placed in multiple foster homes. In 2000, 43 percent of kids were moved three or more times, and 11 percent were moved five or more times. Only a quarter of kids stayed in one home.

“A year to a child is a very long time,” says James Mayer, executive director of the Little Hoover Commission. “For children to thrive, they need a stable, loving environment. This is even more the case when a child has been abused. Some people say that impermanence is the nature of foster care, but we think the system needs to overcome its nature.”

In Sonoma County, kids stay a median of a year and a half in foster care and a little over three years in group homes. As for multiple foster homes, during a six-month period in 2001, 40 percent of Sonoma County foster children were moved twice, 18 percent were moved three times, and 5 percent were moved four times. A little more than a third were placed only once, according to the UC Berkeley Center for Social Services Research.

However, these numbers aren’t always as dour as they sound. For example, if a foster family moves to a new house, it is counted as a move for the child because the new house has to be inspected, but it doesn’t have the same emotional impact as moving to a new family. “Sometimes the data can be misleading,” says Bauer.

Though the federal government was satisfied that California kept siblings together when placing them in the system, the Little Hoover Commission says that only 40 percent of siblings are placed together. If so, it may point to the shortage of foster parents.

“There’s just not enough foster homes in Sonoma County,” says Millie Gilson, director of CASA, a group that works with the local child welfare system to provide kids with child advocates and a stable individual they can go to in need. “The county tries to match foster kids with compatible families, and there aren’t enough parents to do that perfectly. Sometimes the kids suffer because of it.”

Children aren’t getting the psychological care they need, something that along with education is especially important to help foster children function as adults. Though services are available, the system is simply overloaded. CASA, for example, has 37 children on its waiting list right now and can only afford to take on 10 to 20 kids at a time.

In fact, a lot of problems could be avoided if the system weren’t so overloaded. Social workers simply have too much work. The average California social worker carries 27 cases at a time, when it should be more like 12.

“It’s hard to provide intensive care when you are as overworked as these social workers are,” says Bauer. “And, frankly, there are a lot of cases in the system that the government doesn’t need to be involved in. There should be more inexpensive or free community services for families, so they can handle their own problems without the government getting caught up in their lives.”

The California child welfare system also puts little emphasis on prevention of abuse, focusing instead on intervention after abuse has already happened. More services and education would help the situation, but there is little funding available for that.

With all of this criticism, it’s hard to know how well the system really works from the outside. Even on the inside, opinions vary. After foster parent Froess saw the state focus on young infants, the age group she chooses to care for, she became optimistic about the system’s ability to place children.

“It took a lot longer for infants to be placed several years ago,” she says. “Then the state decided to fast-track young children, and now the system does seem to work. We get them into new homes quickly. I don’t see a lot of failures.”

For Martino, the system has had more ups and downs. Though it has worked for some of her foster children, the system has let her other children down, especially the teenagers. In Sonoma County, younger children are put in foster homes while many teenagers are sent to group homes, where they often lead institutionalized lives.

“In some group homes, the kids have to ask to use the bathroom or to go down the hall, so they have trouble thinking on their own and making decisions,” says Martino. “Everything has been severely structured for them. It’s difficult as a foster parent to see that. It’s not something you can completely fix in six months to a year.”

And when these children turn 18 and leave their highly institutional lives, the system shuts its doors and they are expected to be adults.

“They have transitional problems,” says Martino. “They will have some money to live on but they’ll blow it all, which is something a normal teenager might do, only they don’t have a family to bail them out. They are expected to be on their feet. And if they fall down, there’s no one there to help them.”

And Sonoma County, with its high cost of living, can be a hard place to start a life when one has no education or family support. Martino is involved in a transitional program that helps foster kids bridge the gap between adolescence and adulthood. Such support systems seem to help foster children become adults. Of the 26 kids CASA has graduated from the system in the last five years, 18 of them are in some kind of higher education.

Sonoma County has different problems and needs than other counties. As a rural community, it has a smaller number of kids (540 compared to approximately 3,500 to 4,500 in San Francisco or Alameda counties), and the abuse issues are rooted less in hard drug abuse than in physical violence and neglect. County care with funding from state and federal agencies is the best way for the system to be responsive to community problems, believes Bauer.

“Having care at the county level allows the child welfare system to look at what the community needs are without too much interference from the state,” she says.

However, the Little Hoover Commission is highly critical of the distribution of care in California’s foster system. It calls the system leaderless, believes that no one is taking responsibility for the system as a whole, and says too many different government departments are involved. A single case can involve the judicial department, social services, services for drug and alcohol abuse and mental health, and the school district. And, as is common with bureaucracy, blame and responsibility are shifted between departments.

As a result, children can end up lingering unnecessarily in the system as they wait for one department or another to complete a task.

“Say a child is in a foster home because the county requires the parents to seek drug and alcohol counseling, but the parent can’t get treatment because of a bureaucratic reason, and the courts can’t terminate parental rights until the parent seeks or refuses treatment,” says Mayer. “In those cases, the child ends up lingering in foster care unnecessarily. The departments need to work together so that sort of thing doesn’t happen.”

In 1999 the Little Hoover Commission issued a report criticizing the child welfare system. Now, four years later, it says that though money has been thrown at the problem, the situation is still the same.

“More funding hasn’t brought improved outcome for the kids,” says Mayer. “A management system is more important than funding.”

The Little Hoover Commission recommends that California designate a position that would oversee the entire system as well as allow for management of individual counties. That way there would be more accountability among the departments.

The Little Hoover Commission’s criticism of the foster system’s structure doesn’t bode well for Governor Gray Davis, who has proposed shifting $8.3 billion in health and welfare programs from the state to the counties.

As for the CFSR, the state has two years to present a plan to the federal government showing how it will improve in the criticized areas. After that, new goals will be set for the state to reach. If the state reaches each goal, it will not have to pay any of the $18.2 million in penalties, according to Orr.

But whether these changes in the system can fix the problems remains to be seen.

“The government doesn’t make a good parent,” says Mayer. “But as a parent, they have obligations to provide competent care, as we would expect from a natural parent, like safety, stability, healthcare, and education. The system won’t be improved until it is giving the children all those things.”

From the February 20-26, 2003 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.

© Metro Publishing Inc.