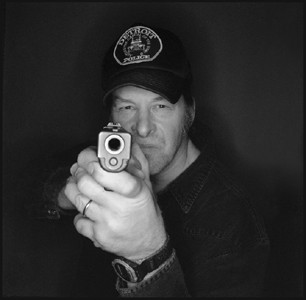

Chef Nuge!: Rocker, cookbook author and hunting enthusiast Ted Nugent has but one motto for the kitchen: ‘Kill legal game. Add fire. Devour.’

Grill Seeker

How George Foreman, Bobby Flay and Ted Nugent taught me to be a real (suburban) man

By Joshua Green

One of the false promises of adulthood is that once you grow up, all the competitive torments of adolescence will magically disappear. As someone who has only recently done that (hitting the adult trifecta of a new job, new wife and new house), I have discovered that’s not the case; in fact, the assorted humiliations I remember so vividly from my teenage years have suddenly reemerged, only in slightly different form.

Let me give you an example. One evening not long ago I stood on my patio, flip-flopped and contentedly sipping a beer in the manner I imagine common to suburban men, pausing occasionally to wipe my brow as I tended earnestly to the bratwursts on my hulking Char-Broil gas grill. The newly initiated male homeowner in my neighborhood quickly comes to understand that despite whatever life has taught him, status really revolves around only three things: home improvement, lawn care and barbecuing.

As a longtime apartment dweller, I hadn’t initially understood that the queer looks I received shortly after moving into my house were due to the nearly waist-high grass that, it turns out, rapidly appears when there is no superintendent to care for it. But I’d quickly fallen in line, and after a single pass from my fearsome, all-terrain Craftsman mower, I was beaming at my freshly manicured expanse of lawn when he first caught my eye: there, in the corner of the yard, was an enormous raccoon. And he was digging furiously. In my lawn!

Confronted by an adversary, my fight-or-flight instincts took hold, and I simply reached for the nearest weapon at hand, a garden trowel, which I hurled at the invader like it was a ninja throwing star. The trowel sailed harmlessly past him, though it removed a sizable chunk from the fence. As I stood there, impotently shaking my fist and cursing the damage to my lawn, it dawned on me how quickly I was shuttling along life’s continuum from Dennis the Menace to Mr. Wilson.

And while, as a species, we project an image of being kings of our castle, eager to show off the recently landscaped yard or hold forth to visitors on the merits of various deck sealants, such knowledge and skill are acquired only under the constant threat of humiliation.

Take my initial foray into grilling. Owing only partly to the diplomatic exchange with the raccoon, my first attempt yielded brats that were somehow totally charred on the outside yet still raw on the inside, a sort of double whammy of unappetizing cooking. Chastened, I decided to sample a number of recently published books on the art of grilling. As in adolescence, adulthood requires that you declare your allegiance to a group, and deciding what kind of a grill cook you’d like to be is a lot like choosing which lunch table you’re going to sit at. My lunchroom choices included jocks, student-council geeks and stoners; the grilling books I picked up broke down along roughly these same lines.

George Foreman’s 1996 tome Knock-Out-the-Fat Barbecue and Grilling Cookbook seemed like a good bet since, having been written by a jock, it looked unthreateningly straightforward and brought back memories of the George Foreman grill that had been a mainstay of my old apartment kitchen. Alas, I didn’t notice that the book is co-authored by a nutritionist or that George explains in the preface that “my eating habits have changed significantly over the years”–a bad omen grimly justified by his making clear that he no longer cares for the delectable burgers his signature-brand grill is so good at preparing.

I’m sad to report that Foreman’s book has a wussified element to it that, while not incongruous with the life of the recent suburban transplant, significantly diminishes the appeal of these recipes. The recipe for Lyndon B. Johnson’s own Texas barbecue sauce, for example, turns out not to be the real thing but a thin “heart-healthy” knockoff. And burger recipes like George’s promising-sounding powerburger reveal themselves to be lightweights, the lean ground beef cut with such atrocities as bread crumbs, oat bran and even textured vegetable protein to shield us from calories.

None of these recipes sounded remotely appetizing enough to attempt, so I decided instead that my long-term enjoyment of grilling would be better served by ridding myself of the troublesome raccoon, who now appeared every evening at twilight to carry out his own vision of landscape gardening right across most of the flower beds. Before turning to my next cookbook, I headed to the hardware store and learned that areas like the one I live in–which bans such common-sense solutions as simply shooting the damn things–present only two choices for the besieged homeowner. I opted first for the most humane choice, a Havahart steel cage trap whose packaging proclaimed it suitable for “raccoons and small dogs.” This label puzzled me, but I went ahead and bought the trap figuring that after I’d captured the raccoon I could keep it in the garage in case the yard was suddenly overrun with Shih Tzus. Per instructions, I baited the trap with bacon and peanut butter, and spent the next several evenings in a seated vigil on the back porch, waiting to hear the sharp snap of the spring-loaded door as I passed the time flipping through cookbooks.

Next in my stack of books was Bobby Flay’s new Boy Gets Grill (Scribner; $30), which looked fussy and remarkably complicated for someone who struggles grilling brats; the author himself looked suspiciously like a grinning ex-student-council weenie. The recipes sounded as if they’d be too much of a chore to shop for, let alone to prepare. Take, for example, smoky-sweet rotisserie apricot-chipotle-glazed lamb tacos with goat cheese and salsa cruda–suitable for some wimpy vintner perhaps, but not for me.

Surprisingly, though, Boy Gets Grill is superb (and not just for grilling) when one adheres to the simple rule of ignoring any recipe with more than six words in the title. This led to my discovery of the delicious extra-spicy Bloody Marys, an excellent sour cream salsa dip for football season and the pressed, Cuban-style burger, among many other treats. While a good deal of the book is given over to recipes I’d never attempt–clams, quail, Cornish hens–special sections on fish tacos, burgers and skewers make this an invaluable resource for the pest-free grilling enthusiast.

Sadly, that did not describe me. Early one morning, groggy-eyed and longing for coffee, I was shuffling into the kitchen when a sudden movement caught my eye through the window. There, behind what remained of the flower beds, sat the steel trap–and this morning, unlike previous mornings, it contained something large and furry. I bolted out to the garage to don protective gloves and confront my nemesis at last. Only it turned out not to be a raccoon but a large, white possum who looked up expectantly, as if hoping I had brought some more bacon.

With a sigh, I bent down, pried open the door and jiggled the cage to free him. The impostor didn’t budge. I grabbed one end and turned the cage practically upside down. The possum simply grabbed hold of the steel wiring with his claws and stayed put. I gave up, figuring he’d soon wander off. But when I returned that afternoon he was still there, curled up and snoozing in his new home, probably dreaming of bacon.

Meanwhile, the quadrupedal lawn terrorist laying siege to my homestead ratcheted up his attacks. He began using our flower boxes as his personal litter box. By this point, I had spent long hours in fruitless pursuit of him, my humiliation capped by the realization that my life now mirrored that of Carl Spackler, the muttering groundskeeper of Caddyshack played by Bill Murray, who ultimately turns to plastic explosives in an apocalyptic struggle to save his fairways.

Returning to the hardware store, I ultimately resorted to an altogether different mode of warfare: powdered coyote urine, which the clerk assured me was the plastic explosive of raccoon removal. I returned home, checked to make sure I was standing upwind and began to powder the lawn, fence, bushes and anything else within shaking distance. The irony of this was painful because–let’s be honest here–until not all that long ago, I was much likelier to be found urinating on someone else’s lawn at 2 in the morning than spreading someone else’s urine on my own lawn at 2 on a Sunday afternoon.

The authors of my final cookbook, Ted and Shemane Nugent, would have no trouble dispatching a raccoon or figuring out what to do with it afterward. The ’70s rock star turned gun enthusiast and his wife wrote the 2002 hunt-and-flame book Kill It & Grill It: A Guide to Preparing and Cooking Wild Game and Fish. The book features recipes for deer, elk, wild boar, rabbit, bear and other wildlife. But it was Ted’s chapter-opening stories of hunting animals with a bow and arrow–or an AK-47–for which I suddenly developed the greatest appreciation.

With my grilling possibilities sharply curtailed due to the powdered lawn and a related fear of a sudden stiff breeze, I can’t attest to Nugent’s claim that “wild game meat has no equal.” (His assurance that it is high-protein, no-fat and low in cholesterol, however, led me to consider sending a note to George Foreman.) But I can say that “Chef Nuge” and his recipes are refreshingly simple and easy to follow, each just a slight variation on his motto: “Kill legal game. Add fire. Devour.”

How useful these recipes prove in practice depends a great deal on one’s degree of culinary adventurousness and the strength of one’s gag reflex. There is sweet ‘n’ sour antelope, squirrel casserole, barbecue black bear and Coca-Cola Stew (the Nuge reports that the acid in Coca-Cola softens and sweetens wild game meat), as well as milder fare like quail roast, pumpkin goulash and even Mom’s blintzes. It should be said on their behalf that aside from exotic game, most of the Nugents’ ingredients tend to be found in any kitchen. My lone foray into Nugent-style cooking was an aborted attempt at stuffed and rolled venison log, for which I proposed to swap ground beef for venison before my wife intervened.

Not long ago, with summer drawing to a close, I was in the garage when a shuffling noise drew my gaze outward to the small window box just outside, where the large, striped posterior of a raccoon was settling in to make itself comfortable. Racing through the back of the garage to the house, I grabbed a carving knife from the kitchen and bolted back out to the yard, aiming to cut off the raccoon’s usual path of escape through the flower bed.

As I burst through the door, I was so filled with rage that I emitted some vague, nonsensical shriek that must have alerted my foe to impending danger, for when I got out of the house, he had already climbed up along the fence where he now stood staring down at me. I charged, chasing him along the fence, through the flowers and crashed through the bushes as he waddled along only to disappear. I stood there burning with humiliation–especially my eyes, which, it occurred to me a moment later, were also burning with powdered coyote urine.

Eventually, the raccoon stopped showing up. My wife believes his assaults on the yard were not directed at me personally. My friends gleefully insist that it was personal and that the raccoon simply tired of tormenting me and sought out a worthier foe. My own hunch is that his appearance is a seasonal thing, and that he’ll be back again next spring. As it happens, I’ve finally mastered the art of grilling brats and decided that that’s really all I need to know about cooking (tip: boil them in beer first). But prompted by Chef Nuge, I have directed my energy to a new hobby, legal in my neighborhood and at which I aim to be proficient by next summer: bow-hunting.

From the December 1-7, 2004 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.