Photographs by Brett Ascarelli

Best tacos: Anastacio Guerra, owner of La Esperanza.

By Brett Ascarelli

Gleaming silver and blue, taco trucks are relatively easy to define. Essentially just kitchens on wheels, they prepare and serve all manner of Mexican food, not just the tacos that give them their nickname. But finding one is another matter.

If you’re lucky, when you ask someone about the location of a favorite taco truck, you’ll get an intersection, the name of a gas station, a nondescript landmark. The vague set of directions suggests, rather than promises, a taco truck’s existence. Ignoring street numbers altogether, directions to taco trucks are like dares or treasure hunts where “X” marks the spot, except that “X” moves around and was last sighted 82 days ago according to some online food-discussion board. Assuming that one might actually find “X,” when should one arrive hungry and expect to leave full? That’s anybody’s guess. Like street numbers, that information doesn’t usually come up. It’s quantitative.

A recent New York Times article, “Chasing the Perfect Taco up the California Coast,” reveals that the critical appetite for Mexican food is growing. But the article would have been nigh impossible to write if, instead of a mere taco, the author had been in search of the perfect taco truck. Taco trucks are transient and almost secretive. To really follow them–if such a thing is possible–is a privileged and hard-won position. You have to be in the know.

In Napa and Sonoma, taco trucks provide a taste of home for laborers who do backbreaking work in the cellars and vineyards of wine country. It’s not the heaps of venture money but, rather, the carnitas that fuels the wine industry–and not only its blue-collar base. The appeal of the taco truck wafts into marketing departments, too.

The online presence of taco enthusiasts on blogs and food websites also represents the hipster crowd’s burgeoning taste for jalapeños, sometimes as an after-party pick-me-up, more often as just a meal. Keith Gendel, 34, is a graduate student at Southern California Institute of Architecture who researched taco trucks for his thesis on makeshift urbanism. Gendel says that catering trucks are on the verge of becoming more trendy, citing a gourmet, organic Japanese-food lunch truck making the rounds–and the news–in Culver City.

Speaking by phone from his Los Angeles home, Gendel emphasizes the ability of the taco truck to bring creativity and life to stale neighborhoods. “The thing about taco trucks is their speed,” he says. “The failure of urban planning is that it’s slow. But taco trucks–as a system, as a network–are a way to instantaneously deploy street life.”

Given all the mystery, it came as no surprise when early this spring a taco truck called El Guadelajara disappeared from Soscol Road, the main strip for mobile-Mex in Napa. There was no closing-up-shop ritual; no newspaper covering the little takeout windows. One week it was there, the next week it wasn’t. Up until that point, it had been my favorite taco truck. After a couple nights in a row without seeing it, an unsettled feeling swept through my belly. The solace of a late-night quesadilla was gone.

Then, out of the blue, a new taco truck appeared in the same spot. It was kismet.

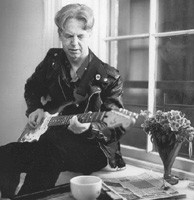

On a chilly evening in April, Anastacio Guerra, 49, is wearing a long white apron over a denim shirt. Standing before his new taco truck, La Esperanza–a vision of quilted stainless steel–he looks slightly suspicious. I have just introduced myself and he seems to doubt my project; am I really an inspector? But he is clearly excited about his new business and it doesn’t take long for him to open up.

Guerra looks at the truck almost giddily. “You need sunglasses when you go in,” he boasts, “it’s so shiny.” I take this opportunity to finagle an invitation.

Like a Transformer toy, the truck is compact but full of surprises. La Esperanza’s 17-year-old truck chassis is outfitted with a kitchen that has been boiled down to its bare essentials. After climbing up a couple of stairs and passing the steering wheel and driver’s seat, I find myself standing in the narrow walkway of a small galley lined almost entirely with sheet metal. A refrigerator and freezer, a number of sinks, steam trays and a grill-top stove are all within a few steps. So are Guerra and his nephew. From here, the small staff (usually no more than three, including Guerra) prepare food to order, turning out tortas, quesadillas, burritos and, of course, tacos. Looking down through a window, the sidewalk is bare. There are no customers.

Back outside, metal awnings, which will collapse to protect a gleaming trough of sodas when driving, make the truck look like a storefront. A mural on the side shows the business’ namesake, a church at the ranch in Mexico where Guerra was born.

This is La Esperanza’s second home in the two weeks since it hit Napa. Its first spot near the recycling center didn’t exactly inspire greatness. Guerra says, “People were tight there,” referring to those who collect cans and bottles for redemption. Grossing a painful $150 per day (to break even, he needs to make at least double that) and having borrowed thousands of dollars from his sister to pay his employees, Guerra moved to El Guadelajara’s old haunt, hearing that the nearby car wash cleans up to 100,000 vehicles during summer.

The stubble peppering Guerra’s chin is the only indication of his often 16-hour workdays. La Esperanza is usually open for 12 hours at a stretch. After closing, Guerra drives it over to a local restaurant that supplies him with the business’ necessary water and food-storage space, and spends two or three hours washing the vehicle down, refilling water tanks and throwing out leftovers. He leaves the truck in Napa overnight and drives the half-hour home to St. Helena where he often only gets two-and-a-half hours of sleep.

When asked if he’s always been a cook, Guerra simply replies, “I cook better than my wife.” Even so, he only recently took the plunge as a mobile restaurateur. In 1974, he took a bus from Jalisco, Mexico, to Fresno (he still has the ticket stub) to work for three months in order to save up enough money to buy a motorcycle when he returned home. Instead, he ended up staying in California, working at a turkey farm and several wineries.

In 1991, Guerra started work as a forklift operator at Beringer, but three years ago hurt his neck seriously and was eventually forced to quit his job. With some time on his hands, he accompanied a friend to buy a taco truck in Los Angeles, and was soon inspired to buy his own. He cashed out his entire 401k to make the down payment, bought the truck and then proceeded to hit a lamppost. New trucks cost between $70,000 and $100,000, depending on the loan. Guerra points out the dent with heroically understated chagrin.

The surprise of the evening is finding out what happened to El Guadelajara. Although Guerra doesn’t know her last name, he reports that the owner, Carmen, moved to Washington state, where she hoped to find less competition. I congratulate myself: penetrating the world of the taco truck turns out to be easier than I anticipated.

And then, La Esperanza disappears.

Hit the Road, Jacinto

Am I worried? No. I have Guerra’s phone number, but calling it would be cheating. I eventually find La Esperanza again on my own. This time, it’s in a new spot, off the main street. In the summer, I visit for the second time. Guerra knits his brows when he sees me.

“I was thinking about you in bed last night,” he says, peering out of the truck’s window. The two women helping him take orders and prepare food raise their eyebrows. He heads outside and explains, “I thought you was an inspector until now.”

Guerra doesn’t look quite as optimistic as he did in April. He had to move La Esperanza to comply with a battery of municipal, county and state regulations. A manager from a chain restaurant had complained that his truck was parked too close to her business. According to Napa city law, taco trucks and other mobile food-preparation units (MFPUs) cannot park within 1,000 feet of a “like business,” meaning a restaurant or another MFPU. The manager called the police who, Guerra says, whipped out the measuring tape. Even though La Esperanza passed the distance test, it had to move anyway. Guerra had violated another rule by parking for longer than 15 minutes on a public street. Actually, he’d been conducting his entire business there for weeks.

But even being stationed in a commercial parking lot doesn’t guarantee immunity. In Napa, MFPUs are technically supposed to high-tail it to a new location, and not return for 24 hours, if no customer has been there for over 15 minutes. Also in Napa, if MFPUs park on commercial property, that property must have a special food-service permit. Furthermore, California law mandates that taco trucks parked in one location for an hour or more must be within 200 feet of a bathroom accessible to employees (“not 200 feet, six inches,” Guerra says he was told).

Yountville and St. Helena, along with all of San Bernardino County, have banned catering trucks altogether. Hazarding a guess about all the antagonism, Guerra shrugs.

“A lot of people love the food, but maybe if I got millions of dollars, I don’t want to see the taco truck.”

Besides the panoply of moving regulations, other matters peeve Guerra. From under his straw hat, he’s looking wistfully at a taco truck anchored in the distance. This is La Playita, and it truly is a little beach–of success. Situated in a prime spot near the Napa Valley Wine Train station, it is not on the public street, but highly visible from it. It stands enviably close to a bathroom, and it offers almost unlimited parking for customers. Guerra covets La Playita’s parking capacity and its following.

La Playita has been a fixture in Napafor 15 years. After selling the original truck and replacing it with a new one, owners Angelica and Isaias Ayala opened La Playita restaurant a couple of miles away on Old Sonoma Road. It’s been there for three years. Both the truck and the restaurant are quite popular among Napa residents and have snagged the approval of the online taco-phile community.

Frustrated by new-kid-on-the-block syndrome, Guerra estimates that the La Playita truck alone pulls in about $2,000 a day. He complains that Hispanics don’t help each other the way that some other ethnic groups do, and echoes something I’ve heard before: that taco trucks are territorial.

Yet Guerra has an alliance with Isaias Ayala’s brother, Carlos Aguilar, who owns La Herradura, a taco truck parked a couple miles away. Guerra and Aguilar even briefly considered buying a restaurant to run as a joint venture.

Guerra is not the only one lusting for La Playita’s spot across the street from the station. The Ayalas once had to take their truck down to Los Angeles for repair, and another truck owner offered the Wine Train money to take over La Playita’s spot.

It didn’t work.

Pugilist at rest: A former delivery van is slowly turned into a taco truck, a process that takes roughly six weeks.

The first taco truck to service Sonoma County arrived during the early 1990s. The ad-hoc industry has boomed in the North Bay ever since. While there are currently about a hundred taco trucks in Sonoma, Marin and Napa counties combined, the number in Los Angeles reaches mythic proportions. Some bloggers estimate that there are between 6,000 and 20,000 trucks, at least half of them registered, roaming the congested web of interstates. (Actually, a total of 2,400 MFPUs, not all of them taco trucks, are registered in Los Angeles county, but at least that many illegal MFPUs are seized each year during near daily sweeps.) Enthusiasts even follow them avidly on the Great Taco Hunt blog (www.tacohunt.blogspot.com).

Los Angeles is the hub of this culture, and as the tender nursery to the taco-truck world, it is responsible for its gradual expansion into the rest of the country.

Practically all taco trucks begin their existences to serve some other purpose–be it industrial or delivery. Once retired, catering truck factories buy the old vehicles and completely remodel them for their new occupation.

In South Central Los Angeles, east of the 110 and a couple of lots away from a recycling plant, some of these tired trucks await rebirth. A handful of staff mill about the office of L.A. Catering Truck Mfg. Inc., which has the comfortable atmosphere of a family business that’s been around long enough that it doesn’t have to hurry. This is where Guerra’s truck, La Esperanza, was born in December 2005.

The factory’s owner, Jorge Gomez, is in his early 40s. Embroidered on his shirt is the company’s logo, a taco truck with its iconic four-paned, blue sunroof pointed toward the sky like parallel fins.

Walking into the plant itself, there’s a faint smell of paint. For its sprawling 25,000 square feet, the factory is almost desolate–only about 18 employees work there. In one room, a lone welder works, nearly crowded out by a sunroof sprawled out on the floor.

Gomez points out a truck that they’ve just begun refitting. The identifying words have been blacked out but are still slightly legible under the spray paint, whispering of its former gig at an industrial parts cleaning company. Save for its skeletal underpinnings, the roof, the back and one entire side of the truck have been cut out in anticipation of a kitchen and a generator. Further on lies a host of metal cutting, welding, bending, notching and patterning machines. Sheet metal is everywhere.

After being lengthened to 16 feet and lowered or raised if necessary, the trucks progress to a painting booth, where one wall is completely covered by air filters resembling a giant loofah. A 35-year-old Chevrolet, masked off and spray-painted dull gray, rests here like a tired boxer mustering up his strength for the last round. An artist has painted the beginnings of a menu in loud orange and blue, the only hint of the street din to come.

Refurbishing some 25 vehicles a year, the factory also doubles as a graveyard and halfway house for MFPUs. Gomez, who started in this business as a taco truck driver himself, explains how a burnt-out truck in the back of the factory met its fate when it suffered an electrical short in Bakersfield. (Sprinkler systems come standard on the newer models.) Although Gomez sells most of the trucks his company makes, they are also available for rent at about $340 per week–a smart choice for some, especially upon viewing a truck that Gomez repossessed after the buyer skipped payments for three months.

Real Deal Appeal

During the recent, brutal July heat wave, Isaias Ayala, the 16-year-old son of La Playita’s owners, considers the spreading taco phenomenon. He’s sitting at a table in his parents’ restaurant where he works when not in school. Mopping his forehead with a napkin, he talks about a Mexican-American who recently started his own business in Germany by bringing a tortilla machine there. “You can’t have Mexican food without tortillas,” he says.

Ayala thinks that taco businesses are multiplying and staking out new territory simply because “people want Mexican food,” especially Mexican immigrants. And even though a lot of the menu items are the same at both the La Playita truck and restaurant, he likes the food better at the truck. Unlike restaurants, taco trucks are equipped with steam trays to keep the food warm, and Ayala says that these hold the flavor in better than restaurant heat counters.

Like other transplanted ethnic foods, Mexican cuisine is vulnerable to “fusion” with the host country’s cooking. For example, one of Paris’ few Mexican restaurants douses burritos with bÈchamel sauce, rather than crema fresca. Closer to home, a popular Mexican restaurant in Napa drowns its burritos with what tastes like spaghetti sauce. The result is like drinking a strawberry milkshake only to discover upon tasting it that the pink color actually comes from Pepto-Bismol.

“Some restaurants sell Mexican food, but it’s more American-style. Here, no,” Guerra says. Taco trucks are fairly utilitarian. They make food to satisfy, rather than to wow.

What La Esperanza and the other taco trucks serve is real Mexican food, as real as you can get this side of the border. It’s made by Mexicans for Mexicans and for anyone else who’s hungry and adventurous. But the point is that the food is not tailored specifically to American taste buds, though Guerra appreciates his American customers and their spending power.

In the end, the effort of taco truck reconnaisance is worth it. For just $5, truck-goers can get a heaping portion of all four food groups. It’s the ultimate comfort food: bigger and more exotic than macaroni and cheese, but still approachable and chewy. The squirt of lime, zing of salsa and the refreshing crunch of radishes sweeten the success of the hunt.

I visit Guerra for the third time on a Friday during summer. It’s twilight, and a respectable line has formed outside La Esperanza. The truck is still in the same place as last time. Guerra seems to be in better spirits today. We stand in the parking lot, discussing how business is going.

He is moving from St. Helena to Napa so that running the truck will be easier, and he says his wife, Sagrario, will soon begin helping him with the business. Orders have picked up now that people can count on him being in the one location. He even has some regulars. On a good day, he is grossing $1,000–still not a luxurious sum, considering expenses and the number of hours of prep and clean-up work involved–but enough to actually profita little bit.

At some point, a waitress peeks her head out of a window on the truck marked “Order Here” and calls something out to him. He excuses himself for a moment and strides across the nondescript parking lot to a white SUV. Peeking his head into the open window, he notifies a young couple that their order is ready. He walks away, muttering, “Maybe that was not the best time.” Apparently, he’d caught them making out.

As evening falls, there’s still a line: Two teenagers on bicycles. A man who works for a cork supplier. Another kissing couple. In the darkening air, La Esperanza glows with the steadfastness of a beacon.

Clean Bean

Sometimes pejoratively known as “maggot wagons” or “roach coaches,” taco trucks are actually quite respectable and are regulated by the state and enforced by the local police and county health departments. California law mandates health and food-safety requirements for refrigeration, water capacity and cleaning procedures. If a taco truck falls dangerously short in one of these or other categories, health officials can shut it down temporarily.

Ruben Oropeza, the environmental management coordinator for Napa County, sees the question of the taco truck as a “complicated, controversial issue.”

“We probably close down on percentage a lot more taco trucks than restaurants,” estimates Oropeza. He says it’s harder for taco trucks to ace health tests because they have smaller refrigerators. When the mercury reaches 90 or 95 degrees, the fridges don’t work very well, especially in the older trucks. Oropeza says taco trucks are also controversial because they can cause traffic congestion and because they can drive fixed restaurants out of business.

On the other hand, both Jerry Meshulam, the Environmental Health Program manager for Sonoma County, and Phil Smith, deputy director of Environmental Health Services for Marin County, report that taco trucks are generally just as safe to eat at as an ordinary restaurant.

“I largely see very positive reports on the condition of the trucks that operate in Marin,” says Smith. “I see a few minor issues, but I’d say I’d be quite happy to purchase food from them, based on the reports.”

In all three counties, at least one of the taco truck’s personnel must pass a food-safety test. Retail food facility permits are stickers usually posted on the back of the taco truck, indicating that they are legal.

–B.A.

Movable Feasts

Sonoma

For the mere pleasure of hunting, the main drag for taco trucks is the Roseland area.

Tacos El Primo The breakfast burrito comes with bacon or ham or chorizo and deliciously savory caramelized onions. Make sure to order this bomb with all the works, as it can otherwise be dry. Located in front of Kenwood Fast Gas, 8850 Hwy. 12, Kenwood. Open daily, 10am-10pm. 707.328.2414.

Tacos El Gitano Another stop for killer breakfast burritos. It starts out at 10am on Broadway in Sonoma, then moves over to Body Best on Eighth Street East at 11am, before moving at noon further down Eighth Street East, just north of Napa Street. 707.579.8814.

Taqueria Santa Cruz Located most nights at the Shell Gas Station on the corner of Payran and Washington streets in Petaluma, this MFPU occupies near-mythic status in the mind of a certain Bohemian music writer. It’s all about the tortilla. Open well into the night.

Tacos Los Magos If you’re lucky, they’ll be serving mariscos (seafood), and there’s always plenty of room to dine at a picnic table in the parking lot. Located on Highway 12 at Boyes Boulevard. Open 5pm-2am. 707.235.9492.

Mariscos Alex Serves a good assortment of meats, breakfast foods and seafood, as well as typical taco truck fare. Last sighted in February 2005, operating 3pm-10pm, at Maria Drive and Park Lane in Petaluma.

Marin

Marin County purportedly has six taco trucks. Of this sparse group, however, only one could be confirmed. Share your fave Marin MFPU with us at ed****@******an.com.

La Pablanita Usually parked at the Belvedere and Bellam intersection, downtown San Rafael. 415.250.6484.

Napa

The main drag for taco trucks is Soscol Road.

Tacos La Esperanza Offering such basics as pastor (barbecued pork), carnitas, pollo and lengua (tongue), this truck’s food has gotten better and better in the few months since its arrival. Try the juicy quesadilla or the perfectly piquant super burrito, which, once you bite into it, is like eating from a soup bowl without the spoon; make sure to ask for extra napkins. Open 11am-11pm daily, on Soscol at Riverside Terrace and Vallejo Street, except Sundays when it parks at the Vallejo Flea Market. 707.695.5513.

Tacos Michoacan This truck recently got mention in the Wall Street Journal for its sumptuous carne enchilada. A staple on the Soscol scene, Michoacan offers a wide range of meats, but it’s not for the faint of heart. The spice here is tongue-singeing. Parked on Soscol, just south of Third Street. Usually open until late at night. Closed Fridays after 2pm. 707.255.5707.

Tacos La Playita A little beach of success. Parked across from the Napa Valley Wine Train station on McKinstry, just off of Soscol. Open 10am-6pm daily. 707.257.8780.

Taqueria La Herradura Usually located at Jefferson and Lincoln, by Kragen Auto Parts. Open 10am-10pm, daily. 707.704.2728.

–B.A.

SEARCH AVAILABLE RESERVATIONS & BOOK A TABLE

View All

Quick dining snapshots by Bohemian staffers.

Winery news and reviews.

Food-related comings and goings, openings and closings, and other essays for those who love the kitchen and what it produces.

Recipes for food that you can actually make.