Coriolanus—bloody and brilliant

Staged as a intimate theater-in-the-round in Ashland’s adaptable New Theater, developed under the wildly inventive direction of OSF mainstay Laird Williamson, the rarely staged Coriolanus—often dismissed as one of Shakespeare’s “problem plays”—has been transformed from a text-heavy, off-putting bore into a bloody, brilliant, tragic, and surprisingly elegant thing of beauty. OSF, which has proven itself adept at bringing the bard’s more difficult works to entertaining life, adds to its reputation with this visually rich, astonishingly well-acted triumph, among the best shows I’ve seen in Ashland this decade.

In a fractured, sleekly modernized Rome, the masses are conflicted about homecoming warrior Caius Martius (Danforth Comins, leaping to star status in his first major dramatic role after five years at OSF).

Though he’s just defeated an invading enemy, almost single-handedly conquering the strategically-placed city of Coriole (thus earning the nickname Coriolanus), his brusque manner, refusal to bow to polite custom, and his constant, war-like attitude, have landed him at the center of a battle between the leaders of Rome and the affronted representatives of the common people. Raised as an arrogant fighter by his manipulative mother Volumnia (a strong performance by Robynn Rodriguez), Martius stampedes and roller-coasters toward doom though a series of personal and political events in which he battles his country, his family, his past, and his own deepest self. Comins plays the part with a transparent, eloquent emotionality, fully illustrating Volumnia’s hasty explanation that “His heart’s his mouth.” As natural and convincing as he is raw and raging. Comins delivers a must-see performance in a season of the strong performances by OSF actors. At the end of the play, his apparent physical and emotional exhaustion is palpable, and entirely well-earned.

As Menenius, Martius’ long-time friend and surrogate father, Richard Elmore makes an equally powerful impression, especially in his final moments, as painful a portrayal of paternal heartbreak as one could ask for. In the small-but-pivotal role of Gneral Aufidius, Martius’ bitter but better self-controlled rival, and leader of the enemy Volscians, Michael Elich is mesmerizing, a watchful volcano waiting the right moment to unleash his fury. Also good are Demtra Pitman and Rex young as Sicinus and Brutus, the roman tribunes who originally set the people against Martius, then quake in fear when he joins the enemy to lead a march against Rome.

The simple set by Richard L. Hay—who designed two of the festival’s three theaters, and who does much of the set designing at OSF—is ingeniously conceived, a slab of stone with a jagged, metal fault-line splitting the performance space as clearly as Rome is split by its own political divisions, as unrepairably as Matrius is ultimately divided from his own truest nature. This Coriolanus is a production savor, to discuss, and, no doubt, to remember for a very long time.

Othello—Villainy and Jealous on the battlefield of Love

There is no jagged crack down the middle of the stage in Lisa Peterson’s grand Othello, but division and disruption are just as much at the heart of Shakespeare’s grand tragedy as they are central to Coriolanus. In Peterson’s gorgeously stripped-down staging, performed on the big Elizabethan stage, the emphasis is on the guy doing all the the dividing. As Iago, one of Shakespeare’s most indelible villains, Dan Donahoe delivers the other great performance of the season, eschewing the snarly cartoon villainy that so often comes with the Iago package, and instead presenting the character as a normal, highly-functioning soldier who’s been eaten-alive by suspicion, competition, and un-named past humiliations. Lines that are usually rushed through— including the rumored mention that his captain, Othello (Peter Macon), may have slept with Iago’s wife Emilia—are strongly emphasized here, and it makes a huge difference. Suddenly, Iago makes sense. He’s not just evil; he’s angry and powerless. What little solace he can have comes from discovering that he is something of a genius at deception. Because it makes him feel better, he sets out to destroy Othello’s brand-new marriage to the lovely Desdemona (Sarah Rutan).

Though the interracial marriage theme cannot be escaped in any production of Othello, this show, as directed, is less about race and bigotry than it is about human frailty and the ease with which love can be turned into hate. Macon, a newcomer to OSF, shows us the giddy, sensitive side hidden beneath the calculated warrior façade, not an easy task, and makes the bold choice of suggesting that beaneath of competent general lies a simmering madness that has, till now, been kept in check. A throwaway line about a conflicted Othello having fallen into “a kind of epilepsy” is staged as a frightening literal seizure, and the site of the imposing Othello thrashing helplessly on the stage is unexpected and deeply moving, a clear sign that there is weakness and vulnerability in anyone and everyone.

In the difficult small role of Roderigo, the love-struck gentleman whose fixation on Desdemona is manipulated by Iago, Christopher DuVal makes a strong impression; he’s a fool, certainly, but a harmless fool, and Iago’s corruption of his trust is as heartbreaking as his destruction of Othello’s fledgling love with Desdemona.

The simple set, with its lone black-and-white slab center stage and bright white lights illuminating the various levels of the Elizabethan theater, lends a sense of contemporary immediacy to the tragic tale. In the end, this Othello is about optimism gone bad, with Iago as its mesmerizing poster boy.

Our Town—classy but flat

Also opening on the outdoor Elizabethan Stage is Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer-winning Our Town, here directed by Chay Yew, with stage-and-screen actor Anthony Heald (Boston Public,Silence of the Lambs) as the omniscient, all-powerful Stage Manager (making less of an impact that one might have expected, given the brilliance of his performances in the past, including last year’s magnificent turn in OSF’s Tartuffe).

In this production, Heald plays the Stage Manager as genial and kind, where a bit of ambivalence and weariness is generally more effective. Starting out as a simple narrator, describing and conducting the actors through a single day in the life of Grovers Corners, circa 1901, the Stage Manager, by the end of the play, has become God, able to grant wishes and even allow the dead a second-chance at life. It is a deceptively difficult role, and Heald, while easily commanding authority, delivers less of the Ancient Almighty than the role demands.

At the center of the play is the relationship between young Emily Webb (Mahira Kakkar) and her next-door neighbor George Gibbs (Todd Burstrom), who are Wilder’s powerfully simple metaphor for the strengths and weaknesses of everyday American life, as we see them court, connect, marry, and ultimately be separated. The cast, called on the pantomime their way through the daily activities of smalltown life, are all quite good, with special attention going to Dan Donohoe (who also plays Iago) as the alcoholic choirmaster Simon Stimson, and Catherine E. Coulson (she was the Log Lady in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks) as Mrs. Soames, whose palpable desperation and loneliness extends all the way to the grave.

In this production, Wilder’s simple, powerful script is staged as written, with little more than chairs and tables as a set, and the inter-racial, multicultural cast are fine at creating the believably lived-in Grovers Corners out of thin air. The story is as quietly forceful as ever, a loving but unsentimental demonstration of American life, love, and death, but as directed by Yew, the pace is too fast for the impact to take root, and the overall result is a disappointing flatness that undermines the play’s emotional power. Tis is a play in which nothing happens, and everything happens, and the pace is crucial. Yew’s Our Town is classy, to be sure, but not nearly as devastating and inspiring as it should and can be.

Further Adventures of Hedda Gabler—A Literary Playground

The name itself is amusing, if something of a literary inside joke. In the large indoor Bowmer Theater, OSF’s Artistic Director Bill Rauch directs Jeff Whitty’s The Further Adventures of Hedda Gabler, which Rauch staged three years ago at Southern California’s South Coast Repertory Theater. If it seems a little funny to make a sequel to a play, Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, in which the lead character blows her brains out in the last scene, make no mistake—it’s a lot funny. In Further Adventures, poor, depressed Hedda awakes to the realization that, as a fictional character, she is doomed to repeat her terrible, unhappy life over and over until there is no one left who remembers Hedda Gabler or Henrik Ibsen.

Played with wicked relish by Robin Goodrin Nordli, Hedda chooses to change her fate. She brings along her servant, Mammie (that’s right, Mammie, from Gone With the Wind, played magnificently by Kimberly Scott, who originated the role in Southern California), herself doomed by her author to be contentedly servile. Pursued by her simpering husband Tesman (DuVal again; great again), Hedda escapes the Cul-de-sac of the Tragic Women, where her next door neighbors are Medea and Tosca, and where everyone seems eager to keep her within shooting distance of her father’s famous pistols. Heading off in search of their respective authors, Hedda and Mammie intend to demand happier endings. Along the way, they encounter a number of famous fictional characters, chiefly Patrick and Steven, a deliberately stereotypical gay couple straight out of The Boys in the Band. Like Hedda and Mammie, they’d prefer to have written differently (not less gay; just less swishy and cliché), but are more understanding of their place in literature. The most challenging, and hilarious, moment comes when the characters stumble into the Verdant Glade of the Christs, where an assortment of Jesus incarnations—from the juggling “clown Jesus” from Godspell to the bloody-drenched “suffering Jesus” of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ—all wander about (“Feel free to browse,” says one of them)

Hilarious and profound, the conclusion of the play is a fascinating meditation on the powers and responsibilites of literature, in which Mamie and Hedda are given a glimpse into why they are such enduring characters, and exactly how long they’d have been remembered had they been written differently.

Archy & Mehitabel—Bugs on the Side

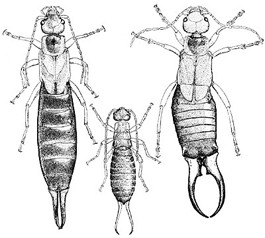

With so much to see at OSF, it seems unthinkable that one could spend a weekend in Ashland and lack for something to do, but with so many shows playing to full houses )aka ‘selling out’), some enterprising theater-goers have discovered that there are other companies staging enjoyable shows in town as well. Last weekend, as OSF was celebrating its opening weekend, the Oregon Cabaret dinner theater was opening a delightful new show of its own: the rarely performed 1957 musical Archy & Mehitabel, written by Mel Brooks and Joe Darion with music by George Kleinsinger. Based on the Roaring Twenties-era poems of New York Sun columnist Don Marquis, A&M is a story of unrequited love between Archy the cockroach (a spectacular Andy Liegl), who lives in a newspaper newsroom and types poems by leaping from key to key on an enormous typewriter, and the over-sexed alley cat Mehitabel (the sexy-funny Bryn Elizan Harris), who keeps getting herself in trouble out on the Bohemian streets of Shinbone Alley. The direction by Jim Giancarlo keeps things moving along, but gives the characters the opportunity to slow down and play the identifiable emotions that are coursing through these very human “animals.” The choreography, by Harris, is fun and frisky, especially that of Archy as he dances on the typewriter keys. The rest of the fine small cast (Joe Massingill, Jessica Price, and Cat Yates) play a combination of street critters, from the various Tom Cats that dally with Mehitabel’s emotions (and occasionally knock her up) to an assortment of street cats, lightning bugs and “ladybugs of the evening.”

Though there can be no romance between a cat and a bug, Archy loves her still, and eventually convinces her to “take a job” as a domestic pet. The results satisfy no one, least of all Archy, who soon realizes he’s lost his best and only firend.

Though this is a show in which people play animals, it should be stated that it is not intended for children, though much of the sexual content is more implied than explicit, Delightfully subversive, and well-suited to the Beatnik era in which it was created, this show is really the story of what happens when a promiscuous kitty is encouraged to abandon her natural instincts, and charts her return to the streets where she is most happily herself. The jazzy, cleverly written songs are sung to a canned score (disappointing; live music is so much better) on a charming set by Norm Spencer. A sneaky surprise by Oregon Cabaret, this charming production, a few quibbles aside, does satisfying justice to this forgotten theatrical gem.

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival runs through the first weekend in November. For information on their full schedule of plays and ticket sales visit [ http://www.osfashland.org ]www.osfashland.org. Archy & Mehitabel runs through August 31 at the Oregon Cabaret Theater. Visit www.oregoncabaret.com