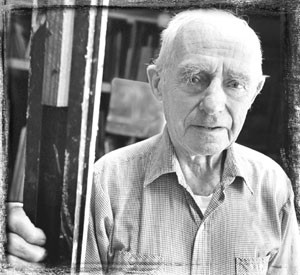

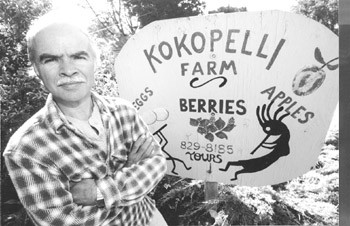

Summer harvest: The author engaged in a months-long process of negotiations with local grape growers.

Building Bridges

A personal view of a successful campaign to stop forced pesticide spraying

By Shepherd Bliss

NO NONORGANIC pesticide application will be made on property without the owner or resident’s approval, reads a joint agreement reached last week by the No-Spray Action Network, the agricultural commissioner, the Sonoma County Grape Growers Association, and other groups. The accord was hammered out during four months at over a dozen negotiating sessions on how to deal with the glassy-winged sharpshooter, an insect that carries a bacterial disease deadly to wine grapes.

The deal is a win-win situation in which both sides basically got what they most wanted: No-Spray, a loose-knit coalition of activists prepared to fight the spraying with civil disobedience, obtained options to forced synthetic pesticide spraying against a resident’s will; and the grape growers–who represent a nearly $2 billion industry–got protection for their crops from the sharpshooter.

At public hearings and in the press during the previous six months, the wine industry and environmentalists fought fiercely over forced pesticide spraying. Sharp words were exchanged before and after the November decision by the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors to permit forced spraying on private property to combat the insect that can bring Pierce’s disease, which now threatens North Bay vineyards.

The new agreement gives people the freedom to choose from four options to control the sharpshooter: mechanical means, such as removal by hand or vacuuming; less harmful organic insecticides and repellents; physical removal of the infested plant; and, as a last straw, synthetic insecticides “with information on their relative safety.”

The accord creates a GWSS Task Force composed of four environmentalists, four grape growers, and one unaligned representative. This group will advise Sonoma County Agricultural Commissioner John Westoby and assist him in dealing with problems. Though Westoby says it is not his intention to spray synthetic chemicals without permission, by state law he does retain that authority.

When Nick Frey, the executive director of the Sonoma County Grape Growers Association, called in February to suggest that growers and environmentalists sit down and talk, I had doubts. We had been opponents in debates before the Board of Supervisors and in the press. I thought that it was worth giving collaboration a chance, but I did not have much faith in it.

Frey also called local No-Spray activists Dave Henson and Brock Dolman of the Occidental Arts and Ecology Center; the Sierra Club; and such unaligned groups as the Community Alliance with Family Farmers and California Certified Organic Farmers.

We all agreed to meet.

My reservations stemmed from participating during l997 and l998 in the early negotiations between environmentalists and the wine industry on the county Hillside Ordinance, originally intended to restrict vineyard construction on steep slopes. After half a dozen sessions or so, I felt the powerful wine industry was more likely to get what it wanted, whereas the environment would continue to be damaged. Since then, working relations between the environmental and agricultural communities had worsened, owing to acrimonious conflict over the failed Rural Heritage Initiative on the l999 ballot.

When No-Spray was forming a team of negotiators to sit down with the grape growers, I decided to remain on the sidelines, listening. Henson emerged as No-Spray’s lead negotiator. After he and others reported on how cooperative and fruitful the negotiations were going, I decided to drop in to sense the tone of the deliberations. I had remembered grape grower Peter Haywood of the Sonoma Valley Vintners and Growers Alliance from the earlier Hillside Ordinance negotiations as an outspoken, adamant, and articulate advocate. Earlier this year we clashed outside the Petaluma City Hall when a No-Spray resolution came before the Petaluma City Council. But here he was, in person, sitting on the other side of the table, and we were looking at each other eye to eye, in a cooperative environment. Though quite protective of his vines, Haywood turned out to be a thoughtful negotiator genuinely interested in solutions.

After our final meeting, Haywood observed, “This process has been very effective in developing standards to have full support of the community. Grape growers are now much better protected by the support of the community. It is likely that the sharpshooter will gain entrance to Sonoma County on private property. It will require participation of the property owner to keep out the [pest]. Support from the entire community is essential for any program to eradicate the sharpshooter to be successful.”

The need for public support helped bring the grape growers to the table. Critical to building public awareness of pesticide dangers were the resolutions against forced spraying passed earlier this year by the city councils of Sebastopol, Sonoma, and Windsor.

Also, No-Spray launched an aggressive campaign to train property owners in civil disobedience and developed a media strategy (as did the grape growers), circulating a statement to activists on “Telling Your Story to the Media.” The media strategy worked. The Press Democrat‘s original articles and editorials tended to favor the wine industry’s view and to demonize this insect. The daily was doing what MIT linguist Noam Chomsky describes as “manufacturing consent” to attack an insect by using deadly poison that would damage people, other animals, and the environment.

But No-Spray began to refute this propaganda with letters to editors; in articles in weeklies such as the Northern California Bohemian (and its predecessor the Sonoma County Independent) and Sonoma West-Times; and on KPFA-FM and KRCB-FM radio. Regional coverage in the San Francisco Chronicle and statewide coverage in the Los Angeles Times were more balanced, as was a report on National Public Radio. CBS-TV’s 60 Minutes recently conducted interviews in the county for a sharpshooter story scheduled for September.

We were about halfway through the negotiations when Westoby joined the deliberations. After the final meeting, he agreed that “this has been a good process–much better than the alternative. It is good to come to an agreement on the goals of detecting and keeping the sharpshooter out of Sonoma County. This is a real triumph.”

Supervisor Mike Reilly concurred: “This agreement is a real accomplishment,” he said, “a credit to everyone who worked on it.”

By the time No-Spray’s final coordinating council met to reach consensus on the agreement, one person suggested making a sign that said, “Support Our Agricultural Commissioner.”

Negotiators from both the grape-growing and environmental communities assured Westoby that they would support him in efforts to protect the local community and provide people choices, including those that are chemically vulnerable. This community support is a key factor in encouraging Westoby to try nontoxic solutions.

Clearly, the grape growers needed the collaboration of No-Spray. The first step toward controlling the sharpshooter is to discover it. If residents do not willingly allow the agricultural commissioner on their property to inspect, it will be difficult to find the sharpshooter. No-Spray activists made it clear that they would not allow the government on their property if it would result in forced spraying. And they would defend the properties of others from forced entry.

IF THE AGREEMENT breaks down, No-Spray plans to engage in civil disobedience to protect homes, yards, gardens, and farms. Marlena Machol of Sebastopol, a grandmother with children who have been damaged by pesticides, notes, “If spraying without permission does occur, the community at large would lose trust in the process and go back to resistance. Then infestation would occur that would not be found until it is too late, because we will not let the inspectors onto our yards and farms.”

At a meeting of five No-Spray affinity groups, Neil Harvey of the Riverbillies observed, “We’ve made a great breakthrough here. But we should not stand down. We need to keep up the pressure.”

The meeting’s consensus was to maintain visibility and to continue building a base for further action, if necessary.

“This document is based on trust and power–our ability to mobilize people,” Dave Henson contends. “It is about creating relationships. By working together for months, we have created a culture of cooperation,” he adds. “Not a legalistic document, this is a statement of principles that establishes a way of working together that hopefully will become a model for the future here and elsewhere in the state.

“Sonoma County will have many other agricultural and ecological issues to address beyond the sharpshooter, and environmental groups will help us resolve those issues as they emerge.”

Shepherd Bliss owns the organic Kokopelli Farm in west Sonoma County. He can be reached at sb*@*on.net.

From the June 7-13, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.

© Metro Publishing Inc.