Declutter, I Declare

Finding peace and harmony amidst all of life’s junk

By Gretchen Giles

We’re gathered here today to talk about the stuff that piles up. The piles that stuff up. The downs of stuff piled. We’re in a Marin County hotel conference room to learn how to shed old books, desnarl forgotten knitting projects, cast off broken car parts, discard rusty tools, and remove the odd hairbrush.

We’ve come together to fervently discuss the spiritual aspects of last week’s newspapers and all of those unanswered e-mails, unopened bills, shoeboxes full of photos, and unread magazines. We will confess to jumbled closets, we’ll yearn toward clean surfaces, we’ll speak of old clothes.

Over the span of two and a half days, we will tremble at geopathic stress, reek of etheric energy, aim toward our astral selves, form a conga line of mass massage, clap at walls, and learn to dowse. There will be saucers full of flowers, there will be incense instruction, endless bells will be rung, and all major credit cards will be accepted.

We seekers have come from Hawaii, from Texas, from Canada and Manhattan and Rhode Island, and from all over California. We are gathered in the pink plushness of the Sausalito Room in Marin’s Embassy Suites hotel to listen to the queen of clutter, Karen Kingston, explain the dire soul-implications of our messy, messy lives. We have paid her lots of tidy money to do this, and we will spend large, amorphous quantities more of it before the weekend is over.

Brining the Ugly Olive

The clutter- and space-clearing workshop led by Kingston begins on a Friday night, and I clip past the hotel’s fake waterfall steaming with chlorine, and wander lost through the bar, where people who presumably have perfectly ordered drawers idly sit before luscious-looking cold cocktails. As it’s been a work day, I am ordinarily attired all in black, a color I am soon to learn attracts malignant energies and may even direct evil spirits right at me with an invisible gotcha snap.

When I finally find the Sausalito Room, some 80 people, exactly four of them male, chat amiably and fix themselves herbal tea while whiny nonmusic drones on in the background. There are no luscious-looking cold cocktails anywhere, nor will there be any caffeine, steaks, or white sugar in evidence until I go to find them myself on Sunday night.

I am the only one dressed in all black, an ugly olive in a grove of life-affirming pastels. By evening’s end, I will be convinced that every evil energy ever conceived in the Sausalito Room is firmly attached to my hem. I take a chair in the back and look around.

This gathering is mostly white, mostly moneyed wives who don’t look like the types to nod earnestly and take notes on chi, evil spirits, and etheric debris. It’s a pantyhose affair, rather than a naked-under-my-batik type of gathering. We look like attendees at a real estate seminar, and, indeed, more than a few workshoppers here are realtors hoping to pick up tips. Others are professional organizers who specialize in helping to unknit other people’s snarls, some hope to study with Kingston, and some appear to lap up weekend workshops like others enjoy weekend hikes. The rest, like me, are just plain disorganized.

A couple confers beside me. “Come up to the front of the room,” the woman coaxes, “and sit with me.”

“I’m just fine here,” the man replies evenly. “Please,” she wheedles. “No,” he says, sounding irritated. “I’m. Just. Fine. Here.”

“Be that way,” she snaps, “I’m sitting up front so I don’t miss anything.” She moves to her seat.

Having stayed his spot, the man says loudly to himself, “Well, you won’t be missed.”

And so we settle down for a pleasant weekend of spiritual instruction on how to clean up all the little messes in our lives.

Sacred Sound Bites

We of the Sausalito Room have come to learn two wisdoms: the art of creating sacred space and the art of clearing clutter. One is pure folk smarts; the other is equal parts human instinct, common sense, lite psychology, and hooey.

We start with the hooey.

Kingston is a handsome, business-like middle-aged Englishwoman. She begins to explain the concept of the etheric. “The etheric is the energy body–what the Chinese call chi, what the Hindus call prana–that runs along our body’s meridians,” she instructs. “It permeates right through us, and we’re exchanging etheric energies all the time, so you may as well get good at it!”

Ugh. I shudder indelicately and look around, imagining that everyone is off-gassing energy like ghostly flatulence and that mine own–the only one that smells good–is rapidly being absorbed and trumped by someone else’s. Color plays an important part in etheric exchange, Kingston explains, which is why light, positive colors emit better than does the death-magnet void of black.

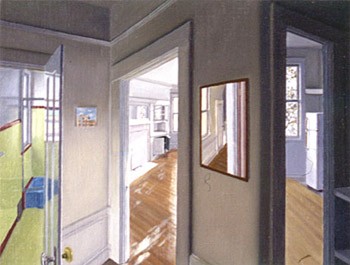

Most importantly, etheric energies can be trapped inside homes, which is why we’re certain to find that if our new home’s previous tenants argued, we will too. If they were fat, you may as well trade up your own waistband. If they were sick, better make certain that your insurance is paid current. No previous homeowners, it seems, are ever happy and successful, making an excellent conscious living while raising lovely children and keeping alive a vibrant, sexy relationship in a glow of perfect health.

I suddenly tune into the “frequency”: Unless you rid your living space of these stale etherics left behind like a gazillion sloughed, dead skin cells from the wretched bodies of the former residents, you’re essentially damned to live their lives over again.

OK, says Kingston, rubbing her hands. Who’s ready for a break?

I am!

Tea for Gandhi

Waiting for tea, careful to keep my etheric energies full and positive but moving directly back toward me where they belong, I stand with quiet patience for the woman ahead of me in line. She’s still registering for the workshop and is trying to settle the final details with one of Kingston’s assistants. I am at peace. I am in no hurry. I am, in fact, deciding in a gentle yet mild and loving way whether I should have the orange spice or the raspberry twig tea.

“Do you mind?” she says to me with a sudden savageness. “It’s perfectly all right to go around me. You needn’t just stand there like that and wait.” I assure her in a voice like Gandhi’s that I don’t mind, but she jerks her head viciously over her shoulder in the direction I am to move along to.

It’s the black, I know it. She’s sensed something from my etherics that’s poisonous and bad, and it’s infected her, making her the madwoman of the tea line! I look back at her and she’s chatting pleasantly with another student, showing teeth and gums in a facsimile of smile. I look in vain for the whiskey tea but must console myself with orange spice. I move my chair further to the back.

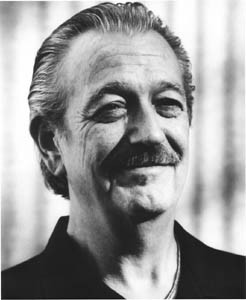

Making Space for Kingston

Karen Kingston lives half of each year in the United Kingdom, and the other half in Bali, where she and her husband run a profitable ecotourist hotel based on her own particular brand of feng shui methods. The author of two books, Creating Sacred Space with Feng Shui and Clear Your Clutter with Feng Shui (Broadway Books), Kingston is a thriving one-woman cottage industry who is as equally clamored for in Austin, Texas, as she is in Stockholm, Sweden.

She tours part of each year giving these workshops; she trains practitioners in her methods; she hosts paying guests at her hotel; and she provides clutter-clearing sacred-space seekers with a chance to purchase her special bells ($130-$200), “Harmony” balls and bags ($4-$50), and altar cloths and “colorizers” for sacred table settings ($17.50-$150). Needless to say, she was completely uncluttered by such items at the workshop’s close.

Something of a savant as a child, Kingston says that she could read, write, and type by age four. By age 11, she had exhausted the contents of her village library, so naturally enough spent her adolescence sulking and smoking.

At 22 she realized she had uncanny talents and could enter anyone’s home and, by feeling through her hands the energy that the walls emitted, tell the stories that had unwound within each structure. Not surprisingly, many of those stories aren’t happy ones, and Kingston began her crusade to clear bad energies through homespun sacred acts and the dissolution of clutter.

Kingston is both warm and scary, as we learned through hearing of her marital arrangements, a story offered as a perfect example of the power of clutter clearing. When she decided that she would like to be married, Kingston also thought that the groom-elect should be Balinese. Living at the time in London, she called the Balinese embassy to inquire how many single Balinese men then resided in the United Kingdom. There were six. She phoned them all, only to discover that they were each already affianced.

Undaunted and preparing to return to Bali, she cleaned out half of her closet and one full dresser drawer in preparation for the belongings of her ghost-groom, whoever he might turn out to be. Once back on the island, she interviewed men for half a year before deciding upon the one who did become her husband. When he accompanied her to London, she says that he was initially shocked but eventually gratified to discover that she’d already made space in her life for him.

Scary like that.

Clear It Out

Ridding one’s home of ugly etherics is no small task, but it’s essential to getting down to the dirty basics of ridding one’s home of ugly clutter. It should not, counsels Kingston, be undertaken if one is menstruating, pregnant, nursing a baby, suffering from eczema, has ingested marijuana in recent months, or has an open wound of any kind. Don’t tempt this on the wild mojo of a full moon.

You may also not perform this on behalf of someone else if he or she either does not agree with such methods or is unaware of them. Dark nasty things are sure to result. Kingston relates the tale of one hospital-bound woman who simply died upon reentering her space-cleared home. She didn’t recognize it. Her built-up etherics were gone, and in mourning, she keeled. Not at all good for the conscience.

One must be in the best possible health and spirit, be preferably unattended, should have the pets stashed outside, and be standing in a clean house or apartment before space clearing. One should not (it now need not even be said) be wearing black.

An altar needs to be erected in each room, featuring a floral or fruit offering, leaves, candles, and incense. The walls have to be swept down–like a human windshield wiper–with one’s arms to release the old energy. Right-angled corners should be “clapped out,” which necessitates an educated adult standing facing a corner and clapping from the ceiling to floor in a rhythmic manner (see “preferably unattended,” above). Bad etherics evidently hate this and flee.

Working in a systematic manner, each room should be cleansed through wiping, clapping, burning, and altaring. Then bells are rung through each to entreat good spirits in, and the final house is “shrink-wrapped” as a visualization in one’s mind, as though an enormous roll of psychic Saran were available to seal in all the good juices one has just evoked. Repeat once monthly or as needed.

The Sacred Skillet

I waver between incredulity and belief. After all, didn’t I once solemnly walk a fiery skillet burning with lavender, sage, and whatever fragrant weeds I could pull from the garden through a house I’d just moved into in order to get rid of the presence of the former resident? I did.

I had performed these rituals with no knowledge of feng shui or space clearing; they had just seemed like natural rites to enact. I could feel the ick of these interlopers and tenants and didn’t want to live with–well, damn–with their etherics.

But Los Angeles-based feng shui consultant Cate Bramble is having none of it. Traditionally trained in Chinese feng shui methodology–which aims to correct people’s relationships to their environments–Bramble maintains the Feng Shui Ultimate Resource website (www.qi-whiz.com), devoted to debunking what she calls the practice’s “snake-oil-and-incense image.”

The author of numerous articles and the forthcoming Architect’s Guide to Feng Shui, Bramble says, “I’m really not sure where space clearing came from. It’s not a part of traditional feng shui. It seems to have some antecedents in smudging, which is Native American, but it’s really just a hodgepodge of New Age crap.”

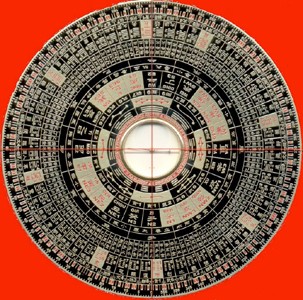

Stressing that feng shui is an “ethnoscience,” as it stems from the traditional ceremonies of indigenous peoples, Bramble has no patience with ringing bells or lighting incense or making flower offerings or shrink-wrapping the house. Feng shui, she insists, involves a compass and a calculator.

“Traditional feng shui is not as sexy,” Bramble says. “It’s from cultures we don’t know and understand. It’s from science, there’s math, there’s having to do things a certain way. Oh my God, there’s a lot of hard work involved. These are all things that Americans don’t want to hear about.”

But what about the assertion that one can feel the energies of a home emanating from the walls? “That’s a bovine by-product,” Bramble quips. “Call [a space clearer] out someplace where you know the history of the house, and ask her to read it–she won’t get it right. It’s the typical con game of fortunetellers and the like, who use clues that you give them to tell you what you want to hear. We are actually giving them permission to fool us.”

Back at the workshop, we all stand and give shoulder massages to people on either side of us. I’m in an agony of embarrassed etherics. We’re instructed to bring pillows the next day and are dismissed.

Ingest, Consume, Eliminate

Saturday dawns, and I dress in pinks and purples, an oversized flower and her pillow floating down the hall to the Sausalito Room. It’s a new crowd today–larger, avid for clutter counseling–and many hapless souls are unknowingly dressed in black. I simper unpleasantly at them and find a seat. I’m careful to choose a different spot from yesterday, due to the possible geopathic stresses that we have learned might be leaking up from the hotel’s floor–nay, any floor!–and which can make us all terribly sick through repeated exposure.

Acolytes anchored, Kingston takes her place. “I have compassion about clutter,” she says, “but I don’t truck in any nonsense about it.” Stipulating that a mess on the outside connotes a mess on the inside, she launches into a day of nuts-and-bolts instruction on stripping down the many dusty reaches of one’s existence.

Simply put, Kingston defines clutter as anything that you don’t both use and love, period. If it doesn’t lift your spirits, provide utile assistance, or simply make you happy, it’s dump fodder. Kingston asserts that by surrounding yourself with unloved and unuseful items, you inadvertently disallow glorious new things to come into your life. You don’t leave yourself room to change and grow. You remain the person you were when you first acquired an object that is now meaningless to you. What’s more, stagnant energies collect around such objects, adding to the psychic weight of the stuff.

Feeling depressed? Look around you. Depressed people tend to leave a lot of stuff all over the floor, and that stuff is just adding to your dis-ease. At least move your piles to higher ground. Clothes? If you haven’t worn an item in a year, it’s clutter. Recycle, gift, or throw it away.

Books? Donate them to a library so that you can borrow them back if you need to. Mail? Open it by a wastebasket and buy a larger one if it fills too quickly. Separate your mail into low, medium, and high priorities. Deal with the high first. If after two weeks your medium or low priority mail has remained unattended, toss it. Creditors tend to get in touch again.

Using the body’s processes as a metaphor, Kingston says, “We eat, we digest, we excrete. When it comes to clutter, people think that they can acquire, use, and keep it. Imagine if you did this with food! You’d explode within a month.” To that end, she also recommends regular herbal colon cleansings.

By all means, she assures, keep a junk drawer; in fact, you can keep several as long as you regularly comb through and discard some of the junk. That knickknack that prevents the mantel from being a paean to the horizontal line may also be kept, as long as it passes the use/love law. Clutter clearing is not an indiscriminate toss of all that you own; it’s about having enough stuff to do what you need to do.

Aye, but once you’ve attained this balance, there’s the rub: Nothing new may come in unless something old goes out. Eat, digest, excrete. Ow.

It’s pillow time. We’re to lie on the floor in an attempt to connect with our higher, astral selves, that part of us unclouded by clutter. Some of us, we are told, will fall asleep. If a neighbor is snoring, please gently shake her awake.

That’s it. I sneak out.

Caught by De-Clutter

Again, Cate Bramble remains unimpressed. On her website, she reviews Kingston’s two books. Of Clear Your Clutter, she writes that it’s “the Puritan obsession with cleanliness married to pop psychology to explain how we run our lives and exhibit emotions through our clutter–how it keeps us chained to the past and fosters disharmony–which links with our sense of identity, status, security, and territoriality. Not a shred of scientific evidence to back it up, and the author actually owes her theories to Calvinist theology. Well, except for the stuff about enemas. There she’s on her own.”

But I’m hooked–except, too, maybe the enema part. I go home and give a cold eye to the house. I can’t bring myself to engage in the hocus of space-clearing it, but I can certainly declutter it. There are the I-hate-my-mom-I-hate-my-elbows-I-hate-my-knees diaries from high school. Out they go. Here is the dress that I wore to a friend’s wedding eight years ago and haven’t donned since. In the Goodwill pile.

There are the 15 photographs of the same baby playing in the same sand on the same day. I save the best one and toss the rest. Gifts I’ve been too polite to discard now seem to be steaming with regret and go quickly out the door. Candle ends, coaster sets, ugly plates, unfinished craft projects, and those two “extra” can openers–gone.

I’d like to boast that since my tenure in the Sausalito Room and its resulting cleaning frenzy, I’ve lived a clear, strict life–a veritable consommé–of use and love. Of course I haven’t. There are several new piles of indiscriminate origin scattered about, and there was that meltdown in Ikea resulting in three new chairs coming in and not one single old one going out. I’m even back in black, spitting a bold raspberry to evil etherics everywhere.

But it has prompted an ongoing interior conversation about what clutter might consist of. Is it people? Sometimes. Is it our schedules, with children and adults passing in and out of car doors all day long in no discernible pattern except that of constant, moving chaos? Just maybe. Was it those diaries, clothes, candle stubs, and can openers? Most definitely.

But is it the full collection of every book I’ve read since 1982, the piles of CDs I might still want to hear on some unforeseen day, or that vintage red silk dress that requires a diet of fruits and seeds for reentry? Absolutely not. As a mere mortal, I’ll pit pure love over use any day–which of course is why Karen Kingston and her space-clearing workshops will continue to fill hotel conference rooms.

From the January 9-15, 2003 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.

© Metro Publishing Inc.