When Conan Nunley, 39, returned from Iraq in 2005, being back in Sonoma did not comfort him, nor make the war in his mind disappear. “I knew I was home,” Nunley says, “but I didn’t feel home.”

Like others who experienced combat, Nunley found that no matter what he was doing, he couldn’t relax. “I was still on high alert. The stress was unbearable—the nightmares, the anxiety attacks. I kept checking for my weapon,” Nunley explains. “At war, you don’t even go to the bathroom without your weapon.” Nunley’s post-combat stress was keeping him from adapting to civilian life. As a consequence he felt isolated, considering himself a “lone wolf.”

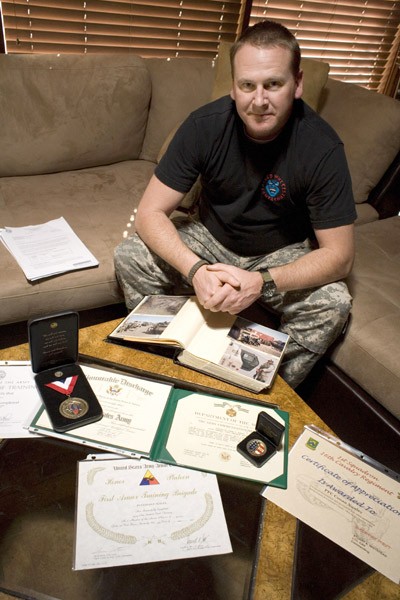

Six years and one military medical discharge later, sitting at an outside table in downtown Sonoma, the broad-shouldered Nunley still sports a boot-camp haircut and talks of leaving his hometown and starting over somewhere. He feels let down.

Nunley is one of thousands of returning vets whose readjustment to civilian life has been hellish. Soldiers bond intensely during combat, yet plenty return from war to find themselves frustrated outsiders. Psychologists evaluating returnees from combat in Iraq and Afghanistan find that these veterans suffer relatively greater mental distresses because combat conditions are more stressful than before.

In contrast to the combat-related wounding of the body typical in previous wars, Iraq and Afghanistan veterans suffer greater psychological wounds. While only 10 percent of Vietnam veterans obtained mental-health services from the Veterans Administration, about 30 percent of returning veterans today are seeking this form of help.

Sadly, the mental-health system was not prepared for a war that would last so long and inflict such a high degree of traumatic stress. As one mental-health worker interviewed for this story explains, “If you get in a bad car accident, you experience trauma. Imagine going back again and again every day and re-experiencing that trauma. That’s what men and women in combat endure for months or years.”

According to the RAND report Invisible Wounds of War, the 1.64 million troops deployed since October 2001 to Iraq and Afghanistan have sustained disproportionately high psychological injuries, primarily post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and traumatic brain injury. The report concludes that these returning veterans are at higher risk of partner abuse, divorce, suicide, substance abuse, heart disease and reduced job productivity that could lead to homelessness.

For Nunley, homelessness was a temporary outcome of the heavy drinking and drugs he used as a coping device for his maladjustment. Now on permanent disability for cognitive impairment, traumatic head injury and other physical reasons, Nunley describes with a touch of bitterness the ineffectual drug treatment program he had to undergo while still in the Army.

“I came up hot for pot on a random drug test, so to save my military career I took a demotion and went to rehab,” he says. “I was 12 days in what was supposed to be a 30-day program, and the VA gave me a certificate of graduation.”

Disappointments come in all forms during war. Chauncey Webster, 21, of Santa Rosa, was a teenager when he joined the Marines as a tonic for boredom. When he deployed to Afghanistan in 2009, he was bored in a different geography. “I was one of the newest guys,” says Webster. “I sat on the sidelines while everyone else got to do what we went over there to do. One of my buddies shot a Mark 19 and killed three Taliban. They were the only ones who shot at us. The locals didn’t bother. They only came around to sell us goats or chickens.”

The locals also peddled hash, which Webster bought for $20 a brick and smoked to pass the time. But all was not calm. Between Christmas and New Year’s Eve in 2010, Webster lost three comrades to the Taliban’s homemade landmines, called improvised explosive devices, or IEDs.

“They make their own explosives with household items and put screws or ball bearings in them, and they put it in a water bottle or a concrete roadblock,” Webster explained. “When it explodes from inside something, it will shoot everything out as shrapnel. Our sergeant major lost both legs when he stepped on one.” One of Webster’s friends stepped on an IED in the shape of a shampoo bottle and was killed from the blast.

Webster was discharged from the Marines for drug use, and he now bears a tattoo in memory of his lost comrades: “Only the dead have seen the end of war.”

Veteran readjustment difficulties were identified collectively as a “public health concern” as early as 2007 in the report Bringing the War Back Home, a study of mental-health disorders among roughly 104,000 veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan being treated by the Veterans Administration during the first five years of conflict. But that study didn’t include vets who don’t go for help, many of whom are resistant due to the stigma—particularly among troops—attached to therapy.

Nunley says that while he was in Iraq, Army superiors advised him and his fellow soldiers that there was someone they could talk to if they were having problems. “But in the military, you’re trained to suck it up,” said Nunley. “You don’t want to be labeled as the guy with the mental problems, as someone who can’t be relied on.”

While this wartime brotherhood may eschew mental-health services, it can be a part of the group healing process during the transition to civilian life, particularly in the residential treatment model created by Fred Gusman, director of the Pathway Home Program in Yountville.

Gusman, a psychological social worker with a military background, has been building and operating trauma centers since the late 1970s. He was on the cutting edge when he created the treatment-center model for veterans returning from Vietnam, and is there at the forefront once again.

“As the war winds down, there will be 30,000 vets returning over the next two years, just in California. After four to six years of military service, these veterans are getting out at age 26 and don’t know how to cope,” says Gusman, sitting in his office. “There were 23,000 California National Guard deployed. If one in three are coming back with adjustment issues, we have a public-health problem.”

Three years ago, the military began posting signs on military bases to encourage servicemen and servicewomen to use mental-health services, but the stigma persists because the culture of the military will be slow to change, says Gusman. In 2008, the problem was so pronounced that the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs changed its rule against using television advertising and launched a public service video starring Gary Sinise, encouraging veterans with suicidal thoughts to call a help hotline.

There is a large amount of goodwill among civilians who want to help returning vets; the public push to provide veterans with jobs, however, fixes only part of the problem. “We should also be providing services for anger, fear, issues about being in crowds,” says Gusman. “We’ve got guys who’ve been back three years, and they’ve tried to go to school, they’ve tried to go to work.”

Without the proper support, veterans often fail in jobs and school. A veteran who has attended military training classes where no disruption is tolerated—and where learning the material can have life-or-death consequences—will find the atmosphere much different and relatively less focused in a college classroom. A new job situation will bring separate challenges and require other kinds of adjustment.

What’s needed for veterans, according to Gusman, is a collaboration in which schooling, employment and mental-health strategies are offered together.

“We have a lot of good things going on for vets, but we don’t have collaboration,” says Gusman, who sees the need to cut red tape and smooth the path for returning vets. “We should be learning from the past. We don’t need to create a chronic population,” says Guzman, referring to Vietnam vets. “Vets need to practice with real people, not just mental-health people.”

A visitor to the Pathway Home Program navigates the spacious grounds of the California Veterans Home in Yountville, stopping at crossings where white-haired veterans of WWII wave amiably from electric wheelchairs, to reach the two-story building leased to the independently operated Pathway Home, one of two PTSD treatment programs in the country that is not affiliated with the military. In the hallway, a whiteboard lists an activity menu that ranges from art therapy and bowling to yoga. Next to an old-fashioned hospital reception desk, a Murphy’s Laws of Combat poster lists dozens of sardonic reminders such as, “Keep in mind that your weapon was made by the lowest bidder.” Next to a miniature American flag in a desktop holder is the familiar black POW/MIA flag.

Residential PTSD programs in the VA vary between 30 and 90 days, while Pathway Home adjusts the length of stay according to individual needs. “We’re the longest program,” explains unit manager Kathy Loughry. “You can’t do this in 30 days.”

What’s more, the Pathway Home Program is free. “The guys don’t pay us to be here,” Loughry says. “And the members are exclusively vets of Iraq and Afghanistan. We don’t have any Gulf War or Vietnam vets in this program. That’s unusual, because if you go to the VA, you get all vets mixed together, which can create a kind of barrier for the group to open up.”

The 32-bed program in Yountville, established in January 2008, has drawn vets with PTSD from all over the country. While in residence, program members take leaves. “A lot of their learning is about how to get back into the community,” says Loughry.

The VA and the Department of Defense already fund four poly-trauma centers at VA hospitals around the country, but the funders of Pathway Home wanted a startup, approaching Gusman due to his development of recovery programs for returning Vietnam vets. Gusman told them that these new returning vets “were going to need what doesn’t exist.”

Now it does exist. Residents of the Pathway Home Program make use of the recreational facilities on the Veterans Home grounds and participate in community activities in Yountville and beyond.

Gusman’s idea of collaboration is working. The program works cooperatively with the VA in Martinez, which provides medications. Program vets have received visits from the Napa Community College, the Sheriff’s Department, the FBI and police, all reaching out to help. Many other community members, both individuals and businesses, have volunteered to assist.

“If you go online, you can find hundreds of good things for veterans,” says Gusman. “There is goodwill, there is good intention, but there is a lack of strategically integrated planning. What we need are collaborators if we are going to be supportive of the returnees.”

Gov. Brown recently formed a committee of state, federal, VA and county mental-health folks charged with developing a program for collaboration. If it works for the Pathway Home, the thinking goes, it can work elsewhere. For the sake of veterans like Conan Nunley—so frustrated by the system that he hired a lawyer to help him get his disability benefits, and who still feels disconnected and adrift—we all have a responsibility to make it work.

—

Where There’s Help

Emergency Hotline

Veterans and their loved ones can call 800.273.8255 and press 1, chat online at www.VeteransCrisisLine.net or send a text message to 838255 to receive free, confidential support 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, even if they are not registered with the VA or enrolled in VA healthcare.

Local Help

County veteran officers and their staff act as a go-between, answering any questions veterans have and directing them to the right services.

Marin: Morton Tallen, 415.499.6193.

Sonoma: Chris Bingham, 707.565.5960.

Napa: Patrick Jolly, 707.253.6072.