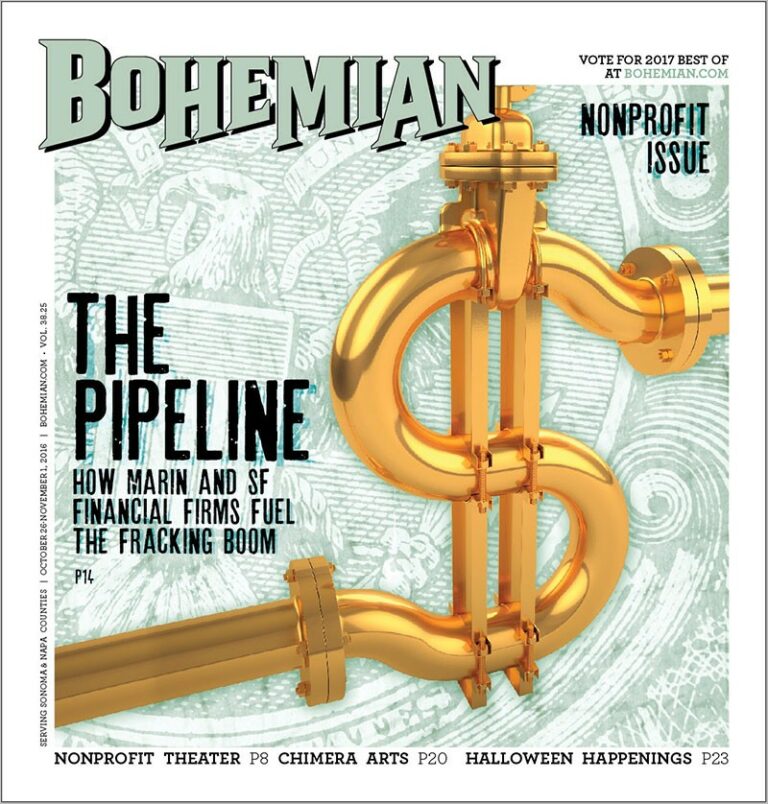

Mill Valley’s Shelterpoint Business Center occupies a narrow strip of asphalt between Richardson Bay and Highway 101, roughly five miles north of the Golden Gate Bridge. In the back of the office complex stands a tan building with floor-to-ceiling windows that offer sweeping views of Mt. Tamalpais’ grassy southeastern slopes. This is the headquarters of SPO Partners, the North Bay’s largest hedge fund.

The serene sophistication of this setting belies the nature of SPO Partners’ business. The

$5.2 billion investment firm is among the country’s leading financial backers of oil and natural gas fracking. Its web of financial connections tie it directly to the country’s most controversial infrastructure project—the $3.7 billion, 1,134-mile Dakota Access Pipeline—and even Republican Party presidential candidate Donald Trump’s economic policy team.

SPO Partners is the largest investor in Oasis Petroleum of Houston, Texas, which controls more than 400,000 acres within the Bakken and Three Forks oil basins of North Dakota and Montana. Oasis is working to complete a 19-mile oil transmission system from its North Dakota petroleum handling facility to the Dakota Access Pipeline, thus positioning it to supply roughly one-ninth of the pipeline’s estimated 470,000 barrels of daily crude oil deliveries, records with the North Dakota Public Service Commission show.

The Dakota Access Pipeline originates in the Bakken oil patch and traverses North Dakota, South Dakota and Iowa, and ends in Illinois, linking to transmission routes to the East Coast and Gulf Coast. For several months, indigenous people, environmentalists and Great Plains residents have protested the project because it threatens water quality and myriad sacred sites of the Standing Rock Sioux. It will also contribute to the global climate crisis.

“Certainly Oasis Petroleum’s hedge fund investors will make a lot more money if the company can supply the Dakota Access Pipeline,” says Antonia Juhasz, a San Francisco–based oil and energy analyst and author who has studied hedge funds and the North Dakota oil boom.

Wall Street tycoon John Paulson, a key member of Donald Trump’s economic policy council, is also a major investor in Oasis Petroleum. According to Oasis Petroleum’s most recent financial filings, SPO Partners owns the largest share of the company, while Paulson’s hedge fund owns the fourth largest. Trump himself has invested between $3 million and $15 million in Paulson’s hedge funds, a 2015 federal campaign disclosure form reveals, raising the possibility that the Republican candidate is also an investor in Oasis Petroleum.

THE MONEY PIPELINE

But the Mill Valley hedge fund’s North Dakota oil investment is only one tributary to a river of investment capital flowing from the San Francisco Bay Area to the Dakota Access Pipeline and the associated fracking boom. These investors include other hedge and pension funds, as well as San Francisco–based Wells Fargo. The bank was the largest U.S.-based financier of oil and gas production and infrastructure as of 2014, according to a presentation given by Wells Fargo executive vice president Mike Johnson.

A recent report from the nonprofit Food & Water Watch notes that 38 banks, Wells Fargo among them, have directly financed the controversial Dakota Access pipeline. The financial sector’s stake in the project helps reveal “the tangle of interests” fueling the United States’ ongoing dependence on fossil fuels, said Food & Water Watch senior researcher Hugh MacMillan, chief author of the report.

“When you see the kinds of financial institutions backing the pipeline, it shows the power of the forces the tribes in North Dakota are going up against,” he says.

FRACKING BOOM

During the last decade, oil companies developed the ability to drill to depths of 5,000 to 10,000 feet before turning their bits sideways, cutting horizontal lines into previously inaccessible rock formations. By fracturing, or “fracking,” deeply buried layers of hydrocarbon-rich shale formations, they force natural gas and oil to the surface. These techniques have revolutionized oil and gas production, yielding hundreds of billions of dollars in profits to investors.

In 2014, the U.S. passed Saudi Arabia as the planet’s biggest oil producer. It has surpassed Russia as the world’s biggest producer of oil and gas combined. Two shale oil basins in particular have helped spur the production surge: the Eagle Ford in south Texas and the Bakken.

Large financial institutions have actively cultivated the North American oil boom. A 2012 Citibank report called “Energy 2020: North America, the New Middle East” notes that “the economic consequences” of the oil and gas industry’s “supply and demand revolution are potentially extraordinary,” and touts that “infrastructure investments ease the transport bottlenecks in bringing supply to demand centers.”

It also sounds a cautionary note: “The only thing that can stop this is politics—environmentalists getting the upper hand over supply in the U.S., for instance; or First Nations impeding pipeline expansion in Canada.”

As with Canadian tar sands oil (see “Crude Awakening,” June 8), the Bakken shale’s Achilles’ heel is that it is located in the middle of the continent, far away from shipping terminals and most oil refineries. That has led many North Dakota producers to transport crude oil by train, including to California refineries, a highly dangerous method given that Bakken oil is especially prone to lethal explosions.

The Dakota Access Pipeline would improve North Dakota oil producers’ ability to compete economically, notes North Dakota Petroleum Council communications director Tessa Sandstrom. It would also reduce deliveries by train, she says, making them safer and freeing up rail lines for farmers to bring their commodities to market.

“This pipeline resolves issues that are big concerns among North Dakotans,” Sandstrom says. “It’s also a legal pipeline at this point, and we think it should go forward.”

[page]

But the extraction of oil, natural gas and coal has driven the planet to the precipice of climate catastrophe. In recent years, the earth has burned through existing temperature records, causing Arctic permafrost to disappear at alarming rates, a process that releases much more carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, thus fueling a dire feedback loop of potentially ever-greater planetary warming. Vulnerable human populations are already being displaced as the ecological fabric that has sustained them unravels.

National and global efforts to cap and reduce greenhouse gas emissions include treaties, taxes and investments in alternative-energy sources and non-automobile transportation. But infrastructure investments that require large, long-term commitments of capital are also crucial indicators of national intent, which is why President Barack Obama choose to reject the Keystone XL tar sands oil pipeline on the eve of the 2015 Paris climate summit involving 191 of the world’s nations.

By completing the Dakota Access Pipeline, one of the longest oil pipelines in North America, the United States would signal to investors its intention to maintain high oil production—and, by extension, high greenhouse gas emission levels. Construction of the pipeline would lead to corresponding increases in fracking, which tend to produce greater emissions than conventional oil.

“The banks are sold on the idea that the U.S. should and will maximize its production of oil and gas,” says Food & Water Watch’s MacMillan. “In doing that, they are banking against any real political effort to keep these fossil fuels in the ground.”

OIL WELLS

According to a 2015 estimate by the Wall Street Journal, banks made about $1 trillion in investments in the energy industry worldwide between 2005 and 2014. In that time, Wells Fargo had seized its position as the top U.S.-based oil and gas banker, with more than $40 billion in investments, according to information published by the data firm Thomson Reuters.

Wells Fargo’s leadership role within the oil and gas industry also includes the annual Wells Fargo West Coast Energy Conference in San Francisco, which brings together leading investors and professionals from across the oil, gas and coal sectors, as well as some who are involved in renewables. This year, the conference took place at San Francisco’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel.

Among the 38 banks that have made loans to companies involved in the Dakota Access pipelines, Wells Fargo has the second largest investment stake, the Food & Water Watch study shows. The San Francisco–based banking giant has loaned roughly

$467 million to the pipeline’s builder, Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), and its family of companies; ETP is among the county’s largest pipeline operators, with a spider-web-like network of other pipelines throughout the Gulf Coast and southwest.

Wells Fargo corporate communications director Jessica Ong says the bank invested in the pipeline only after a review of its potential for social and environmental harm.

“The Dakota Access Pipeline project was evaluated by an independent engineer to be compliant with the ‘equator principles,’ a framework adopted by Wells Fargo in 2005 that is designed to determine, assess and manage social and environmental risks and impacts of projects,” Ong says, adding, “While we respect the differing opinions involved in this dispute, Wells Fargo does not take positions on public policy issues that do not directly affect our ability to serve our customers or support our team members.”

Wells Fargo is more than just a financier of the project. It also acts as ETP’s administrative loan agent, meaning it performs the record-keeping associated with all the company’s loans, handles the interest and principal payments made in connection with those loans, and monitors their ongoing administration. In other words, all bank financing ETP receives passes through Wells Fargo.

FRACKING FUNDERS

Dozens of comparatively small companies, many of them from the Bay Area—such as Farallon Capital Management, Warburg Pincus, Hellman & Friedman, and Hall Capital Partners (the managers of which are developing a controversial Napa County vineyard)—have been major fracking investors, competing to profit on the Bakken and other oil basins’ hydrocarbon resources. San Francisco–based hedge fund BlackRock Fund Advisors is Oasis Petroleum’s sixth largest investor. Think Investments, which is also based in San Francisco, checks in as the eighth largest.

The Wild West character of the Bakken region’s oil industry has also left many companies prone to takeovers by private equity companies and hedge funds that invest in a variety of assets, largely avoiding direct regulatory oversight due to federal laws that exempt companies with relatively small numbers of investors from Securities and Exchange Commission reporting requirements.

“You have lots of smaller companies coming and going, which are very easily bought by wealthy asset managers like hedge funds,” says Juhasz.

[page]

In a September Rolling Stone article, she criticized these investment partnerships’ “exclusive focus on the bottom line and profits, to the detriment of safety and lives, forcing companies to cut corners and do more with less (including tens of thousands of fewer workers), and contributing to a worker death rate in North Dakota that is seven times the national average.”

California-based pension funds are also major investors in shale oil and the Dakota Access Pipeline. The California Public Employees Retirement System, CalPERS, the nation’s largest state-run pension fund, owns a stake in ETP worth $41.4 million, making it the pipeline construction company’s 36th largest institutional investor.

Jane Vosburg of the groups Sonoma 350 and Fossil Free California has attempted to convince CalPERS and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System to divest from fossil fuels. “So far, they have not acknowledged the urgency of the climate situation in our meetings with them,” she says.

Last year, the California Legislature did pass a bill divesting state public pensions from investments in coal.

MADE IN MARIN

Marin County’s SPO was founded in 1991 by a group of investors including William Oberndorf and John Scully, a pair of Stanford business graduates. For several years, SPO was also the lead investor in the Houston-based utility corporation Calpine, among the country’s largest producers of gas-fired electricity. In the North Bay, Calpine is best known as the owner of the Geysers, the famed geothermal power station near Calistoga.

Oberndorf and Scully are also among the biggest investors in a California political action committee that funds business-friendly Democrats and Republicans alike, with an agenda centered on pension reform and public investments in charter schools.

In 2014, SPO Partners began scooping up significantly greater shares of oil and gas drilling companies after global oil prices plunged and numerous producers entered bankruptcy. The firm has more than $1 billion staked in Pioneer Natural Resources, one of the main producers of oil in the Permian Basin and Eagle Ford shale basins of Texas, considered to have more recoverable oil deposits than any other oil basin in the world outside of Saudi Arabia.

Another SPO-invested company, Resolute Energy, has its corporate office in Larkspur, on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, and is the main oil and gas drilling partner of the Navajo Nation, an American Indian nation that has sought to develop oil and gas resources.

Oasis Petroleum is SPO Partners’ third largest oil and gas investment. Records from the North Dakota Public Service Commission show that Oasis’ transmission line is one of six “gathering lines” from different companies that will feed the pipeline.

Scully is also the largest career contributor to Assemblymember Marc Levine, D-San Rafael, having donated $122,500 to Levine’s Assembly campaigns and to a Levine-affiliated political action committee called Elevate California, which ironically sponsored a 2014 campaign mailer advocating for a California fracking moratorium.

Levine sees no conflict in taking Scully’s money. “I’m grateful that [he] agreed with my position that we should have a moratorium on fracking in California,” Levine said. He said “a number of different donors supported” the Elevate California campaign, although filings with the California Secretary of State’s office show that Scully and his wife gave $102,000 out of the $105,500 in outside donations the group received in 2013–14.

Representatives of SPO Partners did not return multiple requests for comment. In 2014, Scully told the Santa Rosa Press Democrat that he doesn’t “disagree with regulating and probably banning fracking in Northern California.” However, Scully said he’s “absolutely for” fracking elsewhere, saying that

“it is working, and it is a significantly good thing for the United States.”

THE OPPOSITION

When construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline began earlier this year, the companies involved regarded the project as a sure thing. In a conference call with investors, ETP CEO Kelcy Warren said he “fully expects” the pipeline to be completed and in operation this year. But because the pipeline runs along the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, a community of 8,500 along the Missouri River in North and South Dakota, tribal members and supporters have camped out in the path of the pipeline route. The blockade and related encampments have galvanized international attention and opened up the possibility that the pipeline may yet be canceled.

In September, the Obama administration bowed to public pressure by denying ETP an easement to construct a 19-mile segment of the pipeline near the Standing Rock reservation, even as construction proceeds across the remainder of the route. In the meantime, three federal agencies are reviewing whether the Army Corps followed proper procedure when it approved the pipeline over the summer.

While California investment capital has flowed to the pipeline, the state has also been a well-spring of resistance to it.

“There have been more people from California out at Standing Rock than from almost anywhere else,” says Sierra Alexander, a Northern Cheyenne tribal member who lives in Willits.

Many California indigenous people who are supporting the Standing Rock struggle have experience battling financial institutions. Billionaire investor Warren Buffett’s investment firm, Berkshire Hathaway, owns four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River. The region’s indigenous people have called for the dams’ removal to protect some of California’s last remaining salmon populations. They have disrupted Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meetings in an attempt to pressure Buffett’s firm. One of the organizers of those actions, Hoopa Valley tribal member Dania Colegrove, is among dozens of indigenous people from the Klamath River basin who have traveled to Standing Rock.

“We’re out here talking about our struggles in the Klamath, and about how nonviolent direct action has changed our world,” Colegrove told a group of dam removal supporters last month in a call from Standing Rock. “We’re helping give the people here the courage to keep going.”

Construction of that final 19-mile pipeline stretch hinges on decisions by public regulatory agency representatives and policymakers, such as President Obama, who could use his authority to revoke the project’s federal permits. The Army Corps of Engineers is the lead permitting agency for the project.

Food & Water Watch’s MacMillan says the importance of exposing banks’ financing of the oil industry—including the pipeline—is that “it lets people know what’s happening behind the scenes.

“The banks are providing the money to make it all happen.”

Contact ‘Bohemian’ contributor Will Parrish at wi*************@***il.com. His website, willparrishreports.com,

is coming soon.