Normally, I wouldn’t let a few downed trees get in the way of a good bushwhack. But as I surveyed the wall of redwood trunks lying across the creek that had been my pathway into the mountains, I had to consider the possibility that I had met my match. Each of these trees was at least 10 feet in diameter, and more than 250 feet long. Piled up like pick-up sticks hurled by a livid giant, the fallen trunks created a formidable barrier to further ascent.

My two companions and I sat down on mossy rocks to assess the situation. Going over the wall of wood was likely impossible without climbing gear, which is not allowed in the park. Going under might have worked, had we brought along snorkels and wetsuits. Going around would entail a battle with head-high nettles that ran up and down the 50 percent grade at creekside. From recent experience, we knew that the climb could take hours and several pints of our blood.

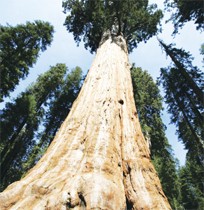

We had come to this remote basin in northern California’s Redwood National Park to hunt for the world’s tallest living tree, a coast redwood nearly 380 feet in height. Explorers had discovered it last summer, in a remnant stand of old growth in the southern section of the park. Growing quietly on a mountainside for centuries, the newly crowned giant is some 70 feet taller than the Statue of Liberty, or about as tall as a 40-story building. Its discoverers christened it Hyperion, after the Titan of Greek mythology who fathered the sun.

The news was followed, as these things must be nowadays, by a press release. E-mailed from the tourism people in Humboldt County, the message claimed that Hyperion “is too far from any trail to visit.” But, it consoled, “adventurers piqued by the discovery have plenty of other opportunities to explore old-growth redwood groves in Humboldt County, the tallest, largest and most pristine in the world.”

Having spent time in Humboldt, I knew the superlatives were well-deserved. But among my several inveterate weaknesses is an attraction to extremes. I’m a sucker for the biggest and tallest and fastest, the super-jumbo jets and Everests and top-fuel dragsters. I hit the reply button and typed a message to Richard Stenger, author of the press release. “Why couldn’t an ambitious hiker visit Hyperion?” I asked.

A few minutes later, Stenger was on the phone. “I gotta tell you,” he said, “this one is really off the beaten path. They say it’s on an incredibly steep slope with thick underbrush that you’d have to bushwhack through. If you knew where to go. But the park folks aren’t telling anyone where it is. Everyone who knows anything about this tree is sworn to secrecy.”

All of which sounded, to me, like a pretty good challenge. And so a few weeks later, I found myself driving up the Redwood Highway with photographer Mark Katzman and photo assistant Derek Southard. We overnighted in Eureka. There, in an Irish pub, Katzman revealed that he was less than confident about our mission. “So we’re just going to show up,” he asked, “with no credentials and no notice, and try to find this tree that no one wants us to find?”

That was essentially the plan–although I had put a call in to the parks’ interpretive specialist, Jim Wheeler. Chief ranger Pat Grediagin was supposedly the only Park Service employee who knew the exact location of Hyperion. The New Yorker magazine had quoted Grediagin as saying “there’s been a lot of talk about this discovery. I’m just worried that someone will get a wild idea to try to find this tree.”

That would be us.

But I reassured Wheeler, on a drizzly Thursday morning when we met him at park headquarters in the town of Orick, that ours was a responsible quest. If we managed to find the tree, we wouldn’t reveal its location, either in print or in conversation. But Wheeler, and the other rangers we would meet, didn’t seem overly concerned about our intentions.

“Mostly,” Wheeler shrugged, “nobody around here thinks you have any chance of finding it.”

According to the rangers and tree researchers, Hyperion’s location needed to remain secret for the tree’s own protection. In the past, vandals and over-adoring fans had injured other champion trees whose locations had been publicized. In the early 1960s, rangers signposted what was then believed to be the world’s tallest tree, making it the centerpiece of the park’s Tall Trees Grove. Ten years and thousands of visitors later, names had been carved in the trunk and the top of the tree had died–an outcome attributed, by at least one scientist, to soil compaction around the roots. Researchers found damage in the crown of another champion redwood, the Mendocino Tree, that suggested it had been clandestinely climbed. Even Luna, the redwood made famous by Julia Butterfly Hill, was deeply gouged by a chain saw a year after Hill had saved it from loggers.

But those trees are near roads and populated areas. Hyperion, by contrast, is far off-trail. Along the Redwood Highway, motorists will happily pay to drive through a tree, but only a small percentage will actually get out of the car and hike more than a few yards from a road, no matter what the attraction. I reiterated to Wheeler that Hyperion’s secret would remain safe with us, if we managed to find it.

“You won’t,” he said.

That night, the Lumberjack Tavern beckoned, its neon sign depicting an axe-carrying logger eyeing a pink martini glass. During boom times, locals apparently stood three and four deep at this bar just north of Orick. But on this night, maybe 15 patrons were inside, most drinking beer through thick beards. Bartender and owner Mark Rochester greeted us warmly. I asked him if he knew anything about Hyperion.

“That *#*&# tree!” he bellowed, setting down a pitcher of local microbrew in front of us. “Don’t get me started!” Rochester had recently purchased the tavern, and was changing its name to Hawg Wild to attract more bikers.

“The Park Service won’t tell us where it is. They’re sitting in their multimillion-dollar headquarters made of redwood that they can cut down and we can’t, and they don’t want us to know where the tree is, even though we supposedly own it. And you know what? When the liberals get in power, there’s going to be even more rules.”

Rochester popped a packaged chicken pie in the microwave, then came back over. “We had no decision in anything the Park Service has done,” he said. “They have systematically choked the life out of this town.”

As he grabbed a Budweiser for another patron, a woman waiting for her shot at the pool table came over to our end of the bar. “I got a different take on it,” she said. “I’m pro-park, and I love trees. But I work at the mill. Sometimes it feels like working in a graveyard. But it pays the rent. And, no, I don’t know where that tree is.”

Moments later, a woman in the corner of the room caught my eye. She came over and leaned close to my ear. “I work for the parks,” she whispered. “And I know too much to even talk to you.”

The next day, I sat down to breakfast with Katzman, Southard and Jerry Rohde, an educator and author who’s written several hiking guides to redwood country with his wife, Gisela. Thin, bearded and bright-eyed, Rohde had agreed to accompany us on our tree hunt, though he cheerfully warned us that the bushwhacking would be “brutal.”

We pushed aside coffee mugs and laid out Rohde’s collection of maps. Triangulating various rumors and hunches, we narrowed our focus down to a few sections of old growth that flanked a couple of small streams that empty into Redwood Creek.

We drove to a trailhead, then hiked down to Redwood Creek. The seasonal bridge had been removed for the winter, so we pulled off boots and gaiters to wade barefooted through the frigid water. On the other side, we put them back on again–only to soak them almost immediately as we headed up a feeder stream.

As we waded upstream, the trees on either side got larger, and the notch that the creek had cut into the mountain got deeper. After an hour of sloshing, Katzman spotted a small piece of orange loggers’ tape, attached to a bush. We scrambled up the steep bank and found that the tape marked the beginning of a short trail, still fairly fresh. It led through thick stands of rhododendron into a grove of redwoods.

We were surrounded by tremendously tall, thick-trunked redwoods–trees that you really have to see to believe. Though the bases were spread across the hillside, the crowns were intertwined in a nearly unbroken canopy, starting about 150 feet above our heads. From the ground it was impossible to tell if any one tree was taller than any other.

On one tree, Southard found a metal tag stamped with three digits. We had assumed that Hyperion would have a tag on it, to mark it as a research specimen. This trunk did seem fatter than the rest, but it was hard to tell whether it was taller. I had brought along a laser range-finder, which uses a laser beam to calculate the height of a target object. But without a clear shot at the top of the tree, the device was useless.

Rohde, who had heard there was a clear cut within a few hundred feet of Hyperion, headed up the slope to try to find a vantage point. He returned and confirmed that there was indeed a clear cut but that it offered no unobstructed sight line to the tree.

Could we have found Hyperion? It seemed too easy. Would the researchers have marked their path with something as obvious as loggers’ tape, visible from a creek–even a creek as little-traveled as the one we were on? Probably not, we concluded as we hiked back to the trailhead.

Santa Rosa amateur naturalist Chris Atkins first visited the redwoods in the 1980s. “I was in awe of their size, their beauty and their longevity,” Atkins says. He found himself drawn back to redwood country again and again. In time, Atkins teamed up with Michael Taylor, who shared his craving for fresh air and biological extremes. Eventually, Atkins and Taylor blew $3,000 apiece on high-end laser range-finders. (Atkins described our range-finder, which cost only $500, as “pretty much useless.”)

Prior to the advent of these devices, measuring a redwood could take all day–if you could even manage to get surveying gear into position. The range-finders allowed Atkins and Taylor to focus their energies instead on the logistics of getting deeper into the parks, to explore the patches of old growth hidden in remote basins.

In the late 1990s, the pair decided to search the entire range of the coast redwood, to document every living tree taller than 350 feet. When they began, only about 25 such trees were identified. As of early 2007, their database contained 136 individual redwood trees exceeding that height–most of which had been discovered by the men. In 2000, Atkins made it into the Guinness Book of Records when he found the 369-foot Stratosphere Giant in Humboldt Redwoods State Park.

“After the discovery,” Atkins says, “someone asked me if we might ever find a taller one. I said the odds were pretty low. We thought we had pretty well mopped it up.”

Redwood National Park has no car-camping sites, and backcountry camping is allowed only on gravel bars in Redwood Creek–not a good idea during rainy season. So we bedded down at the Palm Motel, a seen-better-days place that’s one of two lodging options in Orick. Owner Martha Peals, a Tennesseean whose card introduces her as “pie-maker, entertainer, bed tucker,” said she hadn’t had “too many up here looking for that tree, but I’ve had people from all over the world come here to see Bigfoot.”

Still, she offered to help. “I’ll tell the waitress in the morning,” Peals said. “Her husband works for the park. Her name is Betsy.” As we headed to our rooms, she called out, “Don’t you worry, I’ll find out where that tree is for ya.”

The next morning dawned sunny and calm. As I sat at the counter in the Palm Diner, Betsy came over with a coffeepot and met my hopeful eyes. “I wouldn’t have a clue,” she said. “And my husband doesn’t know, either. They won’t tell him where it is.”

I was halfway through my lumberjack omelet when Rohde called to say that his knee, which he had tweaked yesterday, couldn’t take another day of bushwhacking. He was staying home.

Indeed, our party had taken a few good hits. Katzman, recovering from rotator-cuff surgery, had jerked his shoulder while hoisting himself over a behemoth log. I had dislodged a waterlogged burl that was my foothold while climbing over a downed tree, and fallen through a brittle web of branches, bruising my hip. Only Southard was unscathed.

“I hope you boys find that tree,” Martha Peals sang out to us as we packed up the truck. “But it’d be even better if you ran into Bigfoot out there. Then you could bring me lots of customers and make me lots of money.”

We stopped by the park’s information center to grab a better map. Wheeler, who was raising the American flag, saw us and shouted out. “Did you find the tree?”

I told him about the tree with the metal tag. Wheeler just smiled and said that there are several trees tagged with numbers, identifying them as subjects of various studies by experts at Humboldt State University.

Before crossing Redwood Creek, we reviewed our clues and concluded that we had probably been up the correct drainage, but on the wrong side of the feeder stream. A green-shaded area on the map identified an extensive grove of old growth on the other side, a little farther upstream. But judging from the bunched-up contour lines, Hyperion’s potential location would be steeper. Much steeper.

The day before, Redwood Creek had been up to our ankles. Now, after a night of rain, it was knee-high. If we got more rain, we would need to hightail it back before the rising water cut off our retreat. As we plunged in, a salmon jumped next to Katzman. I followed him, scanning the mountainside above us. Somewhere up there, the world’s tallest living thing was quietly growing ever taller.

Sixty million years ago, redwood forests covered much of the Northern Hemisphere. But as a result of climate change, and then harvesting, the three species of redwood are now found in only three small areas. The giant sequoia, the world’s largest tree in terms of total volume, grows in 70 isolated groves in California. The dawn redwood, once thought to have been extinct for 20 million years, has been discovered in remote valleys in central China. The object of our quest, the coast redwood, is found along a 40-mile-wide, 470-mile-long strip in northern California and southern Oregon.

The coast redwood is no mere mortal tree, and I mean that in the most literal sense. Its scientific name, Sequoia sempervirens (“forever-living sequoia”), refers to its ability to regenerate. Under the right conditions, a single tree can live for 2,000 years or longer, protected by a foot-thick bark layer that is fire- and insect-resistant. Like other conifers, a redwood can regenerate from seeds. Should it topple, it can also regenerate from sprouts that shoot up from fallen trunks, thereby keeping its genetic line unbroken over millennia.

But the coast redwood has an Achilles’ heel: a shallow root system that grows only a few feet under the surface. The trees that blocked our ascent up the creek had most likely been on the losing end of an epic wrestling match with the wind. As a gust levered one tree’s roots free of the earth and sent it hurling toward the ground, the falling giant would have bumped into one or more of its neighbors, setting off a domino effect that would, within a few seconds, bring millions of pounds of wood down across the creek.

As Katzman, Southard and I sat on the mossy rocks, we could see small green shoots coming up at intervals along the trunk, making tentative forays into the misty air. We considered our options. The prospects of going over, under or around looked equally unpalatable. We decided to go through the middle.

Then we continued climbing up the stream until, at a bend, we began ascending the steep bank. We pushed through sword ferns seven feet high, getting soaked in the insanely humid environment. We struggled through fields of brambles, scrambled over the debris of more fallen trees, and found little solid ground to stand on.

I tried my luck at walking atop the inclined trunk of a downed redwood. It had looked like a viable route up the hill, but halfway along I was reduced to shimmying, riding the slippery tree like a horse. Eventually, the tree bucked me off and sent me sliding sideways down a carpet of moss and decaying slime. I fell through a mat of sticks and leaves and into a hidden void. After thudding to the ground, it occurred to me that if Hyperion really was anywhere nearby, it was in little danger of being overrun by bushwhacking throngs.

In the late 1970s, as the U.S. Congress debated expanding Redwood National Park, the pace of logging picked up dramatically. Pushing ever deeper into the area that would soon be off-limits, timber crews set up floodlights powered by mobile generators, allowing around-the-clock work. By the time President Carter signed the expansion legislation, about 80 percent of the soon-to-be-annexed land had been logged. On March 27, 1978, the chainsaws finally fell silent, less than 200 feet from Hyperion. The tallest known tree on earth had been two weeks, maybe less, from its demise.

It would take three decades for anyone to notice the tree. On Aug. 25, 2006, Atkins and Taylor were bushwhacking through a remote basin that neither had previously visited. They had recently found two huge trees–371.2-foot Icarus and record-breaking 375.3-foot Helios–in a nearby grove.

After many years of tree-hunting, Atkins and Taylor had developed a keen intuition. They knew with a glance which trees might be worth a two-hour bushwhack; they knew how to find the “sweet spots,” as Atkins describes them, from which a laser shot might be possible.

Taylor was walking about 100 feet ahead when Atkins noticed a redwood crown looming above its neighbors. Atkins recalls that he got his range-finder out of his backpack and shot at a point just below the top of the tree. He couldn’t see the base, but he estimated that the tree had to be at least 360 feet tall.

“Michael!” Atkins yelled. “Get over here! This tree’s incredibly tall.”While Atkins crossed the creek to bushwhack up the slope, Taylor went to the tree and began calculating the elevation of the base. Atkins eventually found a window through the foliage and lay down to get the laser as steady as possible. From that position, he shot the tree’s top. Then he began working his way back to Taylor, adding and subtracting the elevations of intermediate targets along the way. After all that, they would come up with a preliminary height–377.8 feet–that would make the tree the tallest living thing on earth.

Katzman, Southard and I spent an hour struggling through a maze of brambles and downed trees to reach our target grove. Then we labored farther to rise above the redwoods, hoping that the clear cut would provide a good vantage point. But it turns out that a 30-year-old clear-cut in a rainforest isn’t a smart place to go for visibility or mobility. Amid the dense saplings and underbrush, we quickly lost our bearings and momentum. We decided to head back down into the old growth.

Our own cheap range-finder was proving fickle, due partly to limitations of the technology, mostly to user inexperience. Trees that were obviously well over 250 feet were showing up as 82 feet. The GPS, too, was useless. Under the dense canopy, I could pick up only one satellite. I stowed the devices in my pack, where they would stay for the rest of the trip.

Among the first people Atkins and Taylor told of their discovery was their friend Stephen C. Sillett, a professor of botany at Humboldt State University. Sillett was the first scientist to climb into the redwood canopy, and he is considered by many to be the world’s foremost authority on the redwood forest.

When Taylor told Sillett that he and Atkins had found a tree that they estimated to be higher than 378 feet, Sillett was floored. Having been out in the forest many times with Atkins and Taylor, the botanist had total confidence in their measurements. But, Sillett says, “nobody expected a tree that tall to be growing that far up the mountainside, in conditions that were less than optimal.” It was, Sillett said, “the most significant discovery in tree height in 75 years.”

The only absolutely accurate method of measuring a tree’s height is to climb into its crown and drop a tape measure from the top. Sillett delayed his ascent for two weeks, until the end of the nesting season of the marbled murrelet, an endangered seabird that inhabits the area. Then he assembled a team to climb Hyperion and verify its status as the world’s tallest tree.

With Atkins, Taylor and Sillett’s wife, Marie Antoine, beside him, Sillett tied fishing line to an arrow. Using a crossbow, he shot the arrow over a branch in the lower crown of the tree. Then he tied a nylon cord to one end of the fishing line and, pulling on the other end, hoisted the cord over the branch. Finally, he attached a climbing rope to the cord and pulled the rope over the branch. After tying off one end to a nearby tree, Sillett attached mechanical ascenders to the hanging end of the rope, and began to pull himself up toward the first branch.

“The lowest branch in a big redwood,” Sillett says, “is higher than the tallest branch of almost any other tree in any other forest on earth. And once you get up there, you realize you’ve got almost another 200 feet to reach the top.”

The crown of such a giant is a gnarled mass of limbs, with bridges of living and dead wood running horizontally from branch to branch, forming a natural structure of struts and girders. Upon reaching the first branch, Sillett set up an elaborate rig of ropes and carabineers, which he used to pull himself up from limb to limb, into the heart of the crown. There, Sillett found blackened chambers in the trunk, hollowed out by an ancient, high-reaching forest fire.

“It’s another world, almost another planet up there,” Sillett told me. “There’s a lot of biological diversity that’s unexpected. On limbs and in crotches, you get these huge accumulations of rich, wet soil, hundreds of feet off the ground. We found salamanders, earthworms, aquatic crustaceans, huge huckleberry bushes, even other trees growing on soil mats. It’s literally a hanging rainforest garden.”

Before Taylor and Atkins began finding exceptionally tall specimens high on mountainsides, Sillett and most other experts believed that the tallest redwoods would grow only in alluvial flats, the silty flood plains near creeks.

“There were taller trees up higher all along, of course,” Atkins says. “But the ones in the low, flat areas were what people happened to see, because getting onto the remote mountainsides was so challenging.”

The fact that Hyperion is located in such an unlikely place suggests to researchers that its height is not such an anomaly. Of particular interest to Sillett is the question of the physiological limits of a tree’s height. In other words, how high can a redwood grow?

Trees suck water upward through microscopic pipes called xylem. As water molecules evaporate from the pores of leaves at the top of the tree, other molecules are pulled up from the roots to replace them, in a journey that takes a few weeks from root to treetop. Redwoods, more than any other tree, can move water to great heights, against tremendous forces of gravity and frictional resistance. But at a certain height, the tension of the water column begins to overstress the tree.

Sillett’s team has used centrifuges to artificially create tension in xylem, and has demonstrated that the limit to a redwood’s height is about 410 feet in southern Humboldt County. In the wetter, cooler northern part of the county, where Redwood National Park is located, Sillett’s preliminary research indicates that the limit may be considerably higher.

“What we’ve discovered about the redwoods’ physiology indicates that they can grow a lot higher than the ones we’ve found,” says Sillett. “Which brings up a sobering thought. Now that 96 percent of the old-growth redwood landscape is lost, we understand that, even in our lifetimes, we almost certainly had trees over 400 feet. And we cut them down.”

According to Sillett’s measurements, Hyperion’s height is 379.1 feet. Chris Atkins believes that the chance of finding an even taller tree is less than 1 percent. “There are so few places we haven’t been through,” he told me. “Then again, there are a couple of basins we haven’t seen yet, and there are rumors of tall trees up there. We’re hoping to get in there in the next few months.”

We were talking over the phone, a couple of weeks after my trip to Humboldt County. Toward the end of a long conversation, Atkins asked me where we had hiked. I named the creek basin we had explored on our last day.

“Wow,” he said. “You managed to find your way into one of the most spectacular groves on earth.” He asked a few more questions, regarding how far up the creek we went, which side we climbed, how high we went. After I described the location, Atkins was silent for what seemed like a long time.

“You were in the right place,” he said finally. “You probably walked right past it.”

I shivered when I heard that. Later, as I looked at some of Katzman’s pictures, I recalled that final day when, pausing to rest on a bed of pine needles, I was overcome by a feeling of insignificance that grew until it became strangely ecstatic.

For all I know, I was sitting in Hyperion’s shadow. But at that moment, the pursuit of a single tree–even the tallest one on earth–seemed inconsequential. The real object of my quest was all around me, a mass of immortal columns strong and generous enough to support the sky.

I’d come here looking for a tree, and discovered a forest.