Deadly Force

Michael Amsler

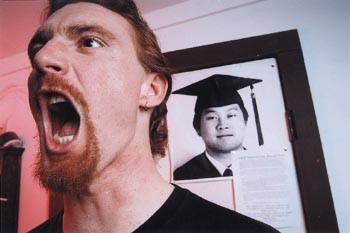

Mad as Hell: Copwatch organizer Jeff Ott is calling for an independent probe into 8 recent police-involved killings in the county–an unprecedented number. But a civil rights panel formed after the shooting last year of Kuan Kao, pictured on the right, by a Rohnert Park police officer will review only deadly-force policies.

Forum on police-involved deaths sparks hot emotions

By Paula Harris

T HERE’S DEFINITELY a lack of mutual communication and respect,” says community activist and Copwatch organizer Jeff Ott when asked to sum up the state of relations between local law-enforcement officials and social justice groups in the county.

At this point, that strained relationship has become even more awkward as the much-anticipated public hearing by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights–which has been reviewing eight local police-involved deaths in the past two years–approaches on a swirl of allegations from those on both sides of the issue.

That hearing was prompted by the April 29 shooting of Kuan Chung Kao, 33, by Rohnert Park Police Officer Jack Shields in a late-night incident that drew national media attention and sparked charges by community activists that the killing was racially motivated.

No one knows quite what to expect from the upcoming hearing, but it’s drawing mixed feelings.

By all accounts, the Feb. 20 hearing will be a vastly toned-down version of what the commission had originally conceived. Instead of a joint forum convened equally by state and federal officials, 11 of the commission’s 16-member State Advisory Committee will preside over the meeting, with the feds announcing last week that they will take a diminished role. In addition, the commission has reversed its decision to subpoena witnesses after objections from law enforcement officials led to a letter of protest from Santa Rosa Police Chief Mike Dunbaugh.

Dunbaugh asked the commission to reconsider its involvement because of the concerns of officers who had already been cleared of any wrongdoing in the cases. “Some people have gone through multiple layers of review and have been exonerated and vindicated,” he says. “They’ve been wondering the whole time if they are going to have to go through this again.”

He and other officials will attend voluntarily, Dunbaugh says, adding that he has not yet been informed about the meeting’s agenda or format.

Tom Pilla, a civil rights analyst for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, says the forum will include an open session at which individuals can discuss law enforcement policies, practices, and procedures. Within several months, the committee will distribute a report and make recommendations to the U.S. Justice Department. The White House also gets a copy.

“This is going to be a starting point,” says Victor Hwang, a civil rights attorney with the Asian Law Caucus who has been critical of the handling of the Kao case. “We’re not going to solve community issues without open dialogue. The good thing [about the forum] is the recognition of how serious a problem this is. After the forum, it will be up to local folks and law enforcement to work together to build some long-term solutions.”

Mary Frances Berry, chairperson of the U.S. Commission of Civil Rights, has emphasized that the hearing will not focus on individual cases of alleged police brutality. That is upsetting to some victims’ families who say they want impartial, independent investigations. The cases already have gone through internal affairs investigations and, in some instances, through a review by the Sonoma County District Attorney’s Office. All the officers involved in the incidents have been cleared.

It appears that the only outside review of the cases most likely will take place in the civil courts, where there are several wrongful-death lawsuits pending over the police-involved deaths, including a $50 million suit filed last week by Kao’s widow, Ayling Wu, against Rohnert Park officials.

“We’re stuck with the court process, which should be the last resort, but in Sonoma County it seems to be the only resort for these sorts of questions,” says John Crew, director of the Police Practices Project for the ACLU of Northern California.

Still, he believes the upcoming forum will provide “a powerful outside analysis” of the deadly-force policies of the police in the county. “We’ve had too much secrecy about police policies, practices, and procedures in Sonoma County,” he says. “If flaws are identified, the forum can encourage reform. If there are no flaws but some misunderstandings, the forum can help correct or explain them.”

Michael Amsler

Under Review: Santa Rosa Police Chief Mike Dunbaugh says he is willing to consider civilian police review boards–if they’re handled correctly.

NOT EVERYONE AGREES. Some critics charge that local police have engaged in cover-ups, and fear that law enforcement officials are holding themselves above the law. “These people are playing judge, jury, and executioner,” laments Darlene Grainger, the twin sister of Dale Robbins, 40, a local man who was shot dead in the lobby of the Santa Rosa Police Department in January 1996 after allegedly wielding a metal steering-wheel club lock at officers. A federal judge subsequently cleared the officer involved in the shooting, but a Sonoma County grand jury report criticized the department’s own internal investigation of the case.

Dunbaugh says the countywide protocol of investigations is currently being rewritten.

Grainger alleges, however, that questions surrounding the circumstances of her brother’s death have never been answered.

The string of officer-involved deaths of eight men in a two-year period began just days after the March 29, 1995, execution-style shotgun slaying of popular Sonoma County Sheriff’s Deputy Frank Trejo, 58, by state parolee Robert Scully, 38. Trejo was the first officer killed in the line of duty in the county in 20 years, and his murder caused some to speculate about police now having a “payback” motive.

“I don’t think there is a pattern–it would be a mistake to make that allegation,” responds Dunbaugh. “What needs to be looked at is that officers are confronted more often in dangerous situations, so if there’s an increase of those situations, then there’s an increase in the use of force to counteract this. The job is much more complicated and riskier. Officers are confronted weekly with people who want to hurt them.”

The Santa Rosa Police Department hires just one out of every 100 candidates tested, he says. “We do a good job of screening people who want to do this job for the wrong reasons.”

A Sept. 17-23 edition of the SF Weekly noted that statistics show that “police in bucolic Santa Rosa kill more citizens per capita than cops in crime-ridden cities like San Francisco and New York.” But Dunbaugh says the stats don’t support the notion that there are more officer-involved shootings of late. “In the last five years in Santa Rosa, there were seven shootings, but there were 11 the five years before that,” he observes.

As for the criticism, Dunbaugh contends that most of the public support the police. He insists that such local activists as the Purple Berets and Copwatch–which have been highly critical of local law enforcement’s actions–are trying to alter that perception.

“[These groups] have every right to have a point of view and be involved in social issues,” he says, “but there are some misrepresentations and what appears to be a strong political agenda overriding senses of good judgment and honesty.”

DURING THE FALL, a coalition of law enforcement officials and local community groups met to iron out their differences. Talks broke down in November after two surprise announcements by law enforcement officials: a county grand jury would design a new review policy to examine all future officer-involved deaths, and plans were under way to create a new civilian police review panel to study police procedures, but not specific cases.

Activists, who had been pushing throughout the year for county and municipal civilian police review boards, felt betrayed by the announcements because the new policies were formed without their involvement. Law enforcement officials countered that the groups had the mistaken impression that the proposed review panel would include representatives from police agencies.

They argued that the grand jury is a randomly selected group of voters and could serve as a model for the panel.

But Nancy Wang of the Redwood Empire Chinese Association and others complained that this is a poor example, since the grand jury is controlled by the district attorney and holds closed-door meetings.

Dunbaugh says that press reports claiming he was against a citizen’s police review board are inaccurate. He now says he is willing to consider it, but adds, “What I’ve experienced so far has been false information, emotion, political agendas, no concern for money or the people it will impact, and an interest in kangaroo courts by a small group of vocal individuals with significant special interests.”

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights public hearing will be held on Friday, Feb. 20, from 8.30 a.m. to 5 p.m. in Room 410 of the State Office Building, 50 D St., Santa Rosa.

From the February 12-18, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.