Screen Scene

Michael Amsler

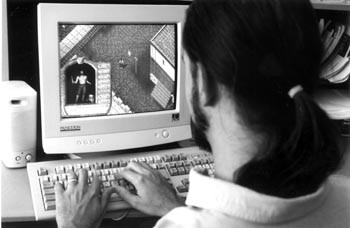

Cyber citizens: A growing number of role-playing gamesters nationwide are swept up in the virtual world of Ultima Online, an Internet game that sports a local server.

Ultima Online: Virtual theater of the fantastic

By Christopher Pomeroy

POROFO, the flaxen-haired neophyte archer from the township of Yew, carefully makes his way through the towering trees of Yew forest. This is the youth’s first excursion from town, and his blood boils with anticipation. The deep wilderness is beautiful, mysterious, and the lush songs of the woodland animals seem, to him, to speak of excitement. What will he find around the next boulder: an undiscovered ruin perhaps, a hungry ogre, a leprechaun’s chest of gold? From behind a tree, suddenly there emerges a man in white robes wielding a sword. He approaches Porofo with the obnoxious gait of a battle veteran.

“You, my friend, have chosen a poor path,” he says.

Naively, Porofo answers with a bow, “Excuse me, good sir, could you perhaps point me to adventure?”

“My name is Whiteshay Lavay, brigand of these woods,” the stranger explains, “and the only point you’ll receive from me is the end of my sword.”

A few moments later, my computer-generated alter-ego, Porofo, is slain, and his murderer is rifling through his equipment.

So much for the wannabe hero. I obviously have a lot to learn.

Thus–with a bit of poetic license–goes my first experience on Ultima Online, a virtual fantasy world and computer role-playing game created by Austin-based ORIGIN Systems Inc., or OSI. Each month, over 90,000 players log onto the game from their home PCs and assume the roles of thieves, wizards, warriors, blacksmiths, and even kings in a world of dragons and dungeons, damsels and dastards.

Ultima Online is the most popular in a growing number of similar role-playing games found on the Internet.

The game, which can be roughly described as a graphical chat room set within a fully interactive, Tolkienesque fantasy world, takes place in the mythical land of Britannia.

The world, based on OSI’s popular Ultima line of solo computer role-playing games, offers 200 million square feet of virtual play area, 12 cities, seven dungeons, and 50 types of fanciful and mundane creatures, and covers terrain ranging from desert to arctic ice. It is so large, in fact, that OSI claims it can take a player as long as 45 minutes to cross its largest city (Britan) and 10 hours to traverse the world.

UO gamers pay a pretty shilling for the pleasure of exploring Britannia: around $60 for the software, plus a monthly subscription service ($10 a month, first month free). The software is available anywhere computer-game software is sold.

To handle the number of players–mainly from the United States, Canada, and the Pacific Rim–OSI has set up nine replica Britannias (same cities, geography, and creatures, but different players) on computer servers scattered throughout the United States. Many local players choose to play on the Mountain View-based Sonoma server (also called “Shard” in game-speak), because of its proximity and name.

Each day, Sonoma Shard plays host to nearly 2,000 players, from Sonoma County and beyond. It is an interesting place: a sword-and-sorcery virtual playhouse in which a drama takes place every hour. However, unlike the thespian craft proffered by your community theater, the Sonoma Shard of UO sports a cast of thousands, with each member writing his or her own lines.

Players Aplenty

JOHN, an avid UO player I met online, cheerfully invites me to his house to explain how the game is played. Or at least, how he thinks it should be played. The Santa Rosa native is a big fellow; not so much fat as burly–the type of casual guy who prefers T-shirts and jeans, regardless of the occasion. John’s computer/game room is an amateur museum for all things fantastic. There are maps of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth, cluttered piles of genre novels, and stone gargoyles perched precariously upon Sheetrock walls. Next to the window hangs a cabinet full of meticulously painted metal figurines, each modeled after a legendary creature or a heroic protagonist.

Lots of swords and buxom women.

Admiring the figures, I remark, “Impressive.”

“Yeah,” he answers, “I’ve two more crates of them in the basement.”

Abundance–that’s one way to describe John. He spends between four to five hours a day playing UO–and on weekends sometimes more. Of course, “dedicated” might fit as well. John, a 24-year-old nursing assistant, takes the game seriously.

“It’s a lot like improvisational acting to me–at least, the way I try to play,” he says. “I love playing a character like someone from fiction. When I was younger, I wanted to be an actor, but I’m not any good at it–my voice is flat, and I’m shy.”

On Britannia, however, it’s a different tale.

John plays several characters or parts on UO, but his favorite is Sven Silvertune, a talkative minstrel who wanders through Britannia almost aimlessly, spreading tales and reciting poetry. Peering over John’s shoulder, watching him control Sven from his keyboard and mouse, I am struck by the quality of the game’s graphics and sounds.

Voyeurlike, I watch the exploits of his onscreen persona as if he is floating 30 feet above his head. The game, which is rendered in three dimensions and 16 million colors, is gorgeous. The trees are vibrant, the cities exciting. Even the sounds draw me into the complex environment: bird songs, footsteps, growls of faraway monsters.

Most interesting, however, is the fact that every time I pass another character, I might be walking by a player from Wisconsin, or Tokyo, or maybe Sebastopol.

Onscreen personae communicate via text, which displays over their heads; they are also capable of a few visual expressions such as bowing and saluting. John explains to me that not all the people Sven communicates with onscreen are controlled by human hands. “They’re robots,” he says. They are controlled by the computer, he explains.

Each Shard, he adds, is populated by a number of computer Non-Player Characters, or NPCs. Just about anyone you run into can be a robot: shopkeepers, healers, beggars. There are a limited number of ways to interact with them, determined by their function in the game. For instance, you can purchase supplies from a shopkeeper, give money to a beggar, etc. NPCs are easy to discern from actual players; they speak in full sentences (most UO players use abbreviations), and they aren’t Britannia’s greatest conversationalists. You can ask a NPC a dozen times what her favorite color is without a proper response.

I know. I tried.

Playing UO, John is focused. His fingers dart expertly across his keyboard, striking special key sequences called macros that allow Sven to perform preprogrammed actions. For instance, if he hits the “alt” key and the “p” key, Sven recites his favorite poem and takes a bow.

John admits he is a bit obsessed with assuming roles. Sven Silvertune even speaks entirely in Elizabethan English–as do the NPCs, by the way–or as close as John can manage.

“I’m not anal about it. It’s not like I majored in the subject. It just seems more appropriate to the atmosphere of the game.”

As interesting as John’s emphasis on online acting is, I find it far from the norm. Most UO players spend their time hunting monsters, earning money, and increasing their persona’s expertise in dozens of in-game skills. For instance, Andy, a 33-year-old Petaluma production worker and a self-described “game freak” since he was a child, is attracted by the strategy involved in becoming a proficient UO player. He can most often be found playing either Genghis, a master swordsman, or the Scoundrel Horndog, a grandmaster thief.

However, no matter what character Andy is playing, he is still essentially himself while in-game–just with different looks and abilities.

Andy, an articulate man whose only real regret about UO is that it interferes with his other love, chess, spends most of his mental energy discovering stratagems to improve his characters and destroy monsters. He excitedly inundated me with schemes to defeat Britannia’s most powerful creatures. His ideas, which he says are common among serious players, are quite clever. One tactic involves tossing bags of flour to block the advance of a demon (a programming function causes the creature to halt movement when his path is obstructed), and then attack it with spells and missile weapons.

Players like Andy who enjoy challenging the UO universe have a lot of in-game tools to manipulate. Each persona has dozens of skills at his or her disposal, as well as an equal number of magic spells, and equipment options. Do you want to be a spell user who can also use a sword? A warrior who forges his own armor? Both and more are possible on UO, and there are compelling arguments for the strategic value of them all.

Mike, a 42-year-old medical equipment manufacturing rep from Santa Rosa, revels in the conundrums served up by such choices. “I’ve actually always enjoyed poring over the charts, looking over data and different categories,” he says. Websites abound that discuss the power and proper usage of skills and weapons in the game. Mike spends a lot of his free time on the game. As we speak, he pauses to interact with another player. I can hear his furious typing through my phone receiver.

The word dedicated comes to mind again.

When I casually mention, “This game seems to take nearly as much time as real life,” his keyboard momentarily silences, and with a light chuckle Mike replies, “I like living in this little world.

“I only wish I could make as much money in the real world as I do on UO.”

When asked how he role-plays, Mike says that he isn’t necessarily playing himself while on UO. “It’s more like me when I was 22 and vice president of my fraternity.”

Fraternity humor is a bit of trademark for Mike online. He said he likes to mix bits of the modern world into the fantasy as subtle jokes.

For instance, he formed a group called the Lords of Morning Wood. Although this sounds like a perfectly acceptable fantasy name, Mike is alluding to a Beavis and Butt-head episode that involved the dawning of a certain portion of the male anatomy. This is not to say Mike is entirely all joke when it comes to UO. He has strong opinions about those who adversely affect play for other players: exploiters who abuse game flaws to create invincible characters, as well as thieves and player killers (called PKs) who prey on new gamers.

Villainous PKs, like that fellow in the opening paragraph, along with the monsters that randomly roam the world, make Britannia a dangerous place to wander. Interestingly enough, this causes even primarily strategy-minded players to join with others socially as a matter of survival.

“You cannot survive or do well on your own in the world. The old saying about no man being an island is very true on UO,” says Andy, who believes this is one of the best aspects the game.

For fun and prosperity, players join guilds, online associations of like-minded gamers. These loose organizations train new players, protect members, and generally provide a hub for people to meet and go monster hunting. Guilds also serve as dramatic flashpoints since members of rival guilds often war against one another. Andy believes the social necessities of UO actually help the development of interpersonal skills.

“I’m not saying that a game should have a social value, but this one does.”

The cyber-community that has evolved on the various UO Shards is one of the most exciting aspects of the game. In fact, experiments in player-created living communities have become one the hottest trends on UO. The Sonoma Shard is home to one of the largest such experiments: the desert city of Oasis.

Sanctuary in the Desert

OASIS is unlike the 12 “official” Britannia cities in that all of its shops, inns, and entertainments are provided entirely by players, as opposed to NPCs. Nestled in one of Britannia’s northernmost deserts, the city was formed by four Sonoma Shard players: Jonas, Flaeme, Lady Rei, and Smitten w/Love. They developed the idea after growing bored with the framework provided by the game.

“After all, you can only slay monsters for so long before it loses its appeal,” says Lady Rei, a graduate student at UC Berkeley. Oasis’ founding is both a story of the ingenuity of its creators and a testament to the flexibility of the game. Built into the structure of UO is a realistic (OK, an economist would balk, but realistic for a game) supply-and-demand economic model, as well as ways for characters to become part of it.

Through the use of persona skills and readily available tools, players can make their own weapons, mine ore, cut lumber, create cabinets, and so on. I was amazed to find out that even something as mundane as baking bread is possible given the right skills, flour, water, and fire.

“We spent a long, long, long (did I say long?) time earning money by collecting a large (350-plus) flock of sheep, which we took turns shearing,” says Lady Rei.

Lady Rei would spin the wool into clothing material that was sold to NPC merchants and other players. The resulting half million gold pieces acquired from their capitalistic enterprise was used to purchase the deeds for the buildings that first formed Oasis.

OASIS HAS BECOME a popular destination on Sonoma Shard; its fame, in fact, has spread to other Shards that have mirrored it with their own player cities. In part, this success has been due to city-sponsored gladiatorial events called “Fight Nights.” During these tournaments, players come to combat one another in a series of battle rings. On such nights, Oasis’ virtual population of 100 can be boosted to as much as 300.

However, Fight Nights are merely a bridge to bring more people to the city. Rei explains that their goal in founding Oasis “was to establish a fully functioning city where players come to role-play their chosen characters in an environment different from the OSI city templates.”

Those who come to fight in Oasis’ bloodfests are not the only denizens of the city. Living in the city are residents such as jesters, bakers, preachers, smiths, loggers, miners, guards, innkeepers, bartenders, and waitresses.

On a good night, when the place is full and the role-players in full force, I have to admit, Oasis is one of my favorite places on UO. It encapsu- lates everything good and bad about the game. Wandering around its nearly 100 buildings are all manner of UO players: gamers, social players, actors, bullies.

In a sense it is alive, and very much like our own world, only dressed in tunics and funny armor.

“I think virtual-world gaming mirrors reality extremely well in terms of the percentages of assholes and pleasant, helpful folk,” says Lady Rei. “As in real life, a few bad apples can ruin the experience for the well-behaved majority.”

Wandering around the city in my guise as Porofo (newly resurrected), I notice a female persona dressed in shimmering plate mail armor warning a new player to avoid the dangers of the wilderness. At the same time, a message pops up on my computer informing me that the gold from my backpack is being stolen.

The thief–“Ha! Ha! Ha!” is displayed over his head–runs away and disappears from my screen.

I still have a lot to learn.

From the October 1-7, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.