April Lance is behind the wheel of her father’s old Ford pickup, talking honeybees as the truck bounces through the Alexander Valley en route to White Oak vineyard and winery for a “hive dive.”

It’s a cool and sunny day in the valley as Lance tells the recent and troublesome history of the honeybee (Apis mellifera). She’s headed to the vineyard to check on two wooden-box hives vineyard proprietor Bill Myers has set up, using local Italian honeybees that Lance breeds and sells. Her bees, she says with pride, are known for their gentle, calm demeanor, and are raised in a chemical-free environment at her place along the Dry Creek in Healdsburg.

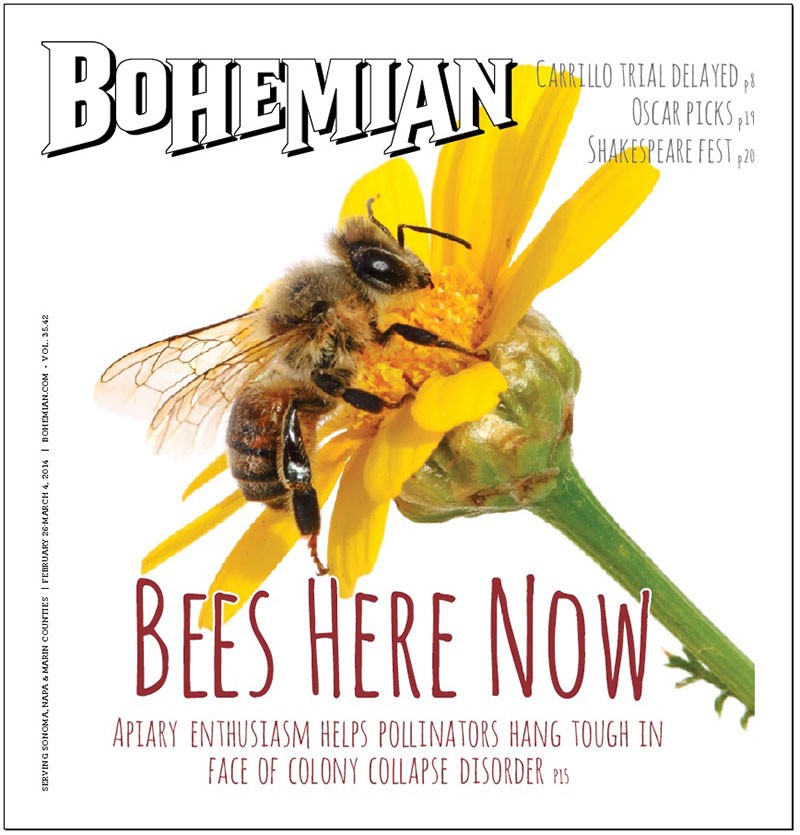

Lance offers many intriguing—and troubling—factoids about the honeybee, industrious apian pollinators in the great ecological cycle of life responsible for about one-third of the food humans consume. Without the honeybee, she says, we’d be eating a diet, basically, of oat gruel.

The bees have been up against the ropes since the winter of 2006–’07. That year, commercial beekeepers around the country and abroad faced an outbreak of a rare phenomenon known as “colony collapse disorder” (CCD). Beekeepers would go out to attend to their honeybees, only to find “empty hives and dead bees all around,” Lance says. “There had been dips before, but the bees had overcome it,” she says. “This was a massive collapse.” The bee situation in Thailand is so dire that farmers there are reduced to hand-pollinating their produce.

It hasn’t gotten that bad in the United States, where lots of research and money has been poured into figuring out the cause of CCD.

On Feb. 25, the U.S. Department of Agriculture said it would provide $3 million to Midwestern farmers and ranchers to help improve the health of bees. “Honeybee pollination supports an estimated $15 billion worth of agricultural production, including more than 130 fruits and vegetables that are the foundation of a nutritious diet,” says Ag secretary Tom Vilsack in a statement. “The future security of America’s food supply depends on healthy honeybees.”

Cause & Effects

The USDA hosted a honeybee conference in 2012 and offered numerous interlocking explanations for the scourge of colony collapse disorder. A report from the conference noted that 10 million beehives had collapsed since the November 2006 collapse, at a cost to beekeepers of about $2 billion.

During the peak of CCD, beekeepers were losing up to one-third of their bees (where the historical annual die-off rate is between 10 and 15 percent). The report noted that the phenomenon had tapered off by 2012, but that the fragility of the bees’ situation was such that any single determinant could kick the collapse into high gear. It identified drought as one such determinant.

The “whys” of the collapse do not fit neatly into one convenient causality, which shouldn’t come as a surprise given the bee’s critical position as an enabler in the human food chain. The Environmental Protection Agency offered attendees of the conference a numbing run-down of the various factors that contributed to the 2006 bee-pocalypse, and it ain’t pretty:

• The invasive varroa mite, a pest that enters the bee’s neck, bores holes in it, and eventually kills it

• “New or emerging diseases” such as Israeli acute paralysis virus and the gut parasite Nosema

• Pesticides applied to crops and used for “in-hive insect or mite control”

The EPA also cited “bee management stress” and “foraging habitat modification” as possible drivers, along with poor nutrition, drought and “migratory stress brought about by the increased need to move bee colonies long distance to provide pollination services.”

Lance adds fungicides to the list and is also concerned (and convinced) that the advent of genetically modified organisms is playing a role in the honeybees’ dodgy health situation over the past decade or so.

Buzzin’ Along

The bees are doing their part to try and survive the various postindustrial onslaughts they now face.

Conscientious and a little neat-freaky, honeybees are hardwired to never die in the hive. “They keep the hives spotlessly clean,” says Lance. If a mouse should enter the hive, the bees will encase the rodent in their wax so it doesn’t befoul the living space.

[page]

They have other interesting habits as well, like only pollinating one plant species at a time. If it’s Tuesday and the hive is pollinating daffodils, every bee is pollinating daffodils. At Myers’ vineyard, they seem to have been snacking on mustard ground cover in an adjacent field. (Grapes, in contrast, are wind-pollinated.) And though they are sometimes confused with the comparatively aggressive yellow jacket, which is a meat eater that can sting multiple times, honeybees are vegetarians that can only sting once, if at all.

Bill Myers is waiting in the driveway as Lance pulls up to the vineyard. An industrious and bustling fellow in his own right, Myers is engaged in some light “biodynamic” vineyard practices here, which includes the bees, some olive trees and a raised-bed garden patch where he’ll grow tomatoes and other produce come springtime.

“He doesn’t make money from any of that,” says Lance, “but he does take good care of the bees.”

Everyone gets suited up in the familiar beekeeper’s garb—the suits are white to keep the bees from thinking we’re bears—and Myers fills Lance in on the activity in his hives as she lights a smoker, which helps further calm the bees during the hive dive.

There’s not much going on inside the first hive, which is made from stacked wooden boxes and filled with man-made honeycomb racks that the bees will use as a basis for their own industrious output of wax and honey. Lance and Myers pry off each of the stacked wooden boxes and perform some sanitizing maintenance on the hive that’s not hosting any bees by giving the wood a light burn with a propane torch. This hive isn’t working, Lance says, because of a lack of available pollen, which itself stems from a lack of available water in drought-stricken California.

The other stack, well, it’s a veritable beehive of activity. Pollen-laden honeybees crowd the entranceway, and thousands of bees buzz about as the hive is taken apart, cleaned and put back together.

Lance spots the queen among her thousands of offspring, and great care is taken to ensure that she is returned to the hive after Lance and Myers finish the hive dive.

The hexagon-shaped pockets are filled with honey, or with bee larvae. It’s a pretty amazing social structure. Honeybee hives are the ultimate matriarchal society—the large queen lives out her days surrounded by an all-male brood, whose lifespan is a frenzied four to six weeks. The queen lays about a thousand eggs a day and will “invite” various wild-eyed suitors into the hive in the springtime, who are known as “drones.” The drones don’t have a stinger; their entire purpose is to mate with the queen bee.

The thousands of in-house bees—the brood—have a honey-do list, so to speak. Some of the brood are guards, who watch over the hive for yellow jackets or other unwelcome intruders; others are foragers, out in the world collecting pollen; and then there are scouts, who head out to see where the hot pockets of pollen are for the rest of the crew. All of them strive to keep the hive at a cozy 98 degrees with heat from their wings, which flap about 200 times a second.

[page]

The hive-minded inhabitants give drones the boot in winter, when it’s just the queen and her brood eating honey they’ve stashed away in the comb—or, if the hand of a human is involved, drinking sugar water from a bottle near the entrance.

With the onset of spring, a new queen is born; the hive splits in two, and the old queen leaves with her brood. These homeless broods are the source of the swarms that North Bay residents will start to see in March, inciting panic, fear and indiscriminate use of insecticides, Lance says.

But truthfully, the swarm is a comparatively less dangerous way to encounter bees, Lance says. They don’t have babies, honey or a hive to protect, and are just flying around looking for a new place to hive-up.

Are You the Beekeeper?

It’s the bimonthly meeting of the Sonoma County Beekeepers’ Association at the 4-H Club in Rohnert Park, and the place is buzzing with activity. In the wake of the 2006 CCD outbreak, North Bay beekeepers flew into action, and local beekeeping groups saw their ranks explode with new members.

Organizations in Marin, Napa and Sonoma counties led public-education campaigns, started monitoring naturally occurring hives and gave nervous homeowners options other than poisoning the bees they’d suddenly discovered had taken a liking to that walnut tree on their property.

Katia Vincent is co-owner (with her husband, Doug) of Beekind in Sebastopol, a store that opened in 2004, just a couple of years before the big bee crisis. As beekeepers and would-be beekeepers start to gather at the 4-H, Vincent marvels at the growth in interest among North Bay residents in the plight of the honeybee. The Marin beekeepers group, she says, had eight members before 2006. “Now it’s huge,” she says. The Sonoma group was a handful of bee loyalists, now it numbers over 400, says attendee Jim Spencer.

A father-son team is chatting up the sign-up folks near the door, expressing interest in becoming beekeepers. Others are sharing information on swarm locations in their towns and trading war stories about the health of their hives. There’s even a guy walking around barefoot.

Katia says her store gets up to 500 calls a year from terrified homeowners, many of whom have already sprayed the bees on their property by the time they call the store. Now there is a network of beekeepers who will go and collect the bees, as an army of bee friends has spanned out across the North Bay to keep an eye out for hives.

She notes that California has protocols and applications for agribusiness when it wants to deploy a particular pesticide or fungicide, but none for home use of pesticides in urban areas. “Individuals are not monitored at all,” she says. “We tell them, ‘Don’t spray, call the beekeeper.'”

Doug Vincent got into beekeeping around 1999, when he was trying to figure out why his vegetable garden was a bust. “Then it dawned on me that what I was lacking was pollinators,” he says. He ordered a kit for amateur beekeepers, “and made every mistake you can make,” he says with a laugh. But within a few years he went from having three, to six, to 25 hives, and before long he and his wife had so much honey they were selling it on the side of the road.

They opened Beekind in 2004 and saw their business double every year for the next six years. “My husband was a quiet fisherman before this,” says Katia. “Now he has bee fever.”

“It just gets into your blood,” says Doug.