Local farming makes a comeback

Rooted

All across the U.S., Americans of every shape, size and skin color are taking up farming and growing vegetables in the spirit of Joy Harjo, the Native American poet who writes:

Remember the earth whose skin you are:

red earth, black earth, yellow earth, white earth, brown earth.

They’re remembering the earth in the North Bay’s valleys and hillsides, and they’re jump-starting the latest incarnation of the worldwide farming movement that comes and goes, from boom to bust and back to boom again.

Right now, the movement is cresting at Radical Family Farm, where Leslie Wiser and her partner, Sarah Deragon, grow Asian vegetables. The two women and their children are newcomers to farming and might need reminding that “radical” means “of, relating to, or proceeding from a root.” Carrots, beets, radishes, corn, turnips and many more vegetables have roots.

Unlike most local farmers, Wiser broadcasts her many identities: “Queer, first-generation Taiwanese-Chinese-German-Polish-American.”

Also, unlike most farmers, she says that her farm is on “Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo land.” Once, all the land was indigenous, though the Native Americans didn’t have European ownership with deeds and titles. They “tended the landscape,” as it’s called, and grew plants, radically.

During the pandemic, local farms and farmers fared well. Vegetables continue to grow despite Covid-19. Farmers markets from San Rafael and Point Reyes Station to Sebastopol and Sonoma sold produce hand over fist, while Instagram helped the farm movement grow by leaps and bounds.

Curiously, some farms keep such a low profile that it’s impossible to find them. I tried to locate County Line Harvest in Marin, but it wasn’t where it was supposed to be, and there was no sign of its legendary founder, David Graetsky. Rumor has it he moved to Thermal, California where he has more abundant land than North of the Golden Gate and more water, which is almost always a worry in these parts.

Oak Hill Reborn

Oak Hill Farm in Glen Ellen, which has been around for decades, is a multi-generational family operation drawing on the resources and skills of the whole Bucklin tribe, which has deep roots in Sonoma Valley. You can’t miss Oak Hill or the Red Barn where produce is sold. For years, Anne Teller, the family matriarch, ran Oak Hill with a team of versatile Mexican field workers and a series of white guys who came and went and sometimes thought they knew most everything about vegetables. Not true.

When Anne passed on May 27, 2019, a month or so shy of her 88th birthday, hundreds of friends, neighbors and family members attended her memorial. In the wake of her passing, the farm descended into near chaos. Anne’s daughters, Arden and Kate, scrambled to get Oak Hill back on track and managed to keep their heads above water, barely.

“The farm was a wreck,” Arden tells me. “Morale was low, the land was depleted and leadership lacking.”

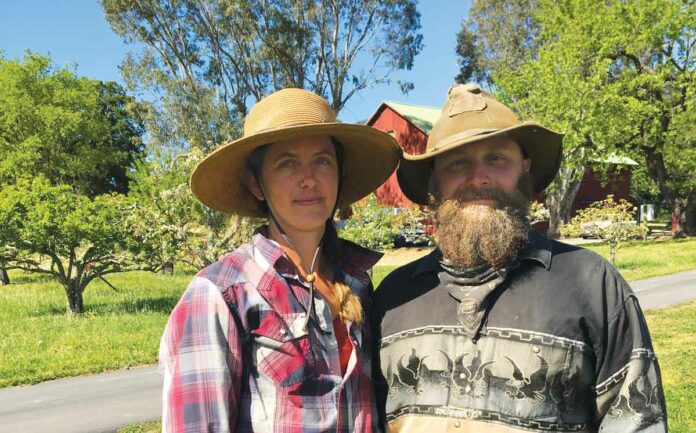

Oak Hill didn’t really find its stride again until Arden and Kate’s niece and nephew, Melissa Bucklin and Jimi Good, both of them young but experienced farmers, relocated from Oregon, put down roots, ploughed fields, planted and harvested, and persuaded the earth to sing again. They also tested and amended the soil, planted cover crops and added compost.

“When Melissa and Jimi first applied to work here, I said ‘No,’” Arden tells me. “I didn’t want more family. But I have come to see that having skin in the game makes all the difference in the world.”

Melissa and Jimi have helping hands from everyone in the family, including those of their 8-year-old son, Bodhi, who minds the chickens and gathers the eggs. Aunt Lizanne looks after the bees and collects the honey, and Melissa’s father, Ted, adds his skills as a carpenter. Kate works on the farm’s infrastructure.

Arden lends her wisdom almost every day. Across Highway 12, a stone’s throw away, Lizanne’s husband, Will, grows grapes and makes full-bodied red wines that go well with pasta, steak and grilled veggies.

Soon after I first met Anne Teller in 2007, she told me, “People come and go, the land remains.” It was hard for me to wrap my head around that idea, but the longer I thought about it the more it made sense. Anne’s second husband, Otto Teller, an avid environmentalist, was gone. Now Anne was gone and so were the two farmers, Paul Wirtz and David Cooper, who aimed to put their own stamp on the land and sometimes clashed with the family matriarch.

On a warm spring afternoon, I sat and talked with Melissa and Jimi, 38, the new kids in the fields. It was obvious that the land remained, though it had been punished by drought and fire, and though field workers came and went. Some went back to Mexico for good. “I’m the greasy thumb and take care of all the farm machinery,” Jimi tells me. “Melissa is the green thumb and spends most of her days in the fields.”

Jimi adds, “In Sonoma the growing season starts earlier and runs later than where we were farming in Oregon. It’s hotter here, and the rainy season doesn’t last as long.”

He and Melissa are learning about the climate and about the people who buy their produce inside the Red Barn at Oak Hill and at the Friday morning outdoor market in the town of Sonoma where locals meet and greet one another, and tourists join the festivities.

“It’s essential to communicate,” Jimi says. “Also, we have to educate our customers, and explain for example how to prepare turnips.” Melissa adds, “People want stuff for salads, so we’re growing more lettuce.”

At Oak Hill there are 90 different species of flowers and dozens of different kinds of vegetables and fruits. “Diversity is the way to go,” Melissa says. “It allows for year-round cultivation and seasonal plantings. You can rotate, not suck nutrients out of the soil and keep a field crew going in all four seasons.”

After 15 months at Oak Hill, she and Jimi seem as settled as any farmers can be. They are balancing what they call “the romance of farming” with the “practically of farming.”

Arden tells me, “My mother would do things differently, but I think she’d be proud of how things are going and growing at Oak Hill now.”

Jimi smiles and says, “There’s nothing more manly than farming.” Melissa adds, “Farming is for everybody.” Arden says that young, college-educated women, more than any other demographic group, want jobs on farms, perhaps because farming is associated with nurturing and harmony with Mother Earth. “It beats the hell out of sitting at a desk and looking at a screen,” she adds.

No longer can a landowner expect migrants from Mexico to plant and harvest. It’s also a challenge to persuade low-income families to buy local produce, which is more expensive than produce cultivated by big machines in the Central Valley. Still, if the pandemic taught Sonoma farmers one thing, it’s that shoppers want vegetables grown close to home. The question, “Is it local?” is heard every Friday at the farmers’ market and in the Red Barn. Arden smiles and says, “Yes.”

The Cannards

There are several beautiful family farms, including Green String, within a 15-mile radius of Oak Hill. Green String is run by Bob Cannard, the grandfather of local, organic agriculture. Bob educated thousands of farmers who now grow crops from Maine and Florida to Michigan and New Mexico. The Green String Store sells honey, vinegar, olive oil, eggs, dairy, meats, fruits and vegetables galore.

Bob’s son, Ross, who studied linguistics at UC Santa Cruz, came home to follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. “Studying linguistics at Santa Cruz isn’t helping me plant onions this morning,” he tells me. Along with his wife, he’s rearing two small children.

Ross belongs to the “returning generation” which is populated by the sons and daughters, grandsons and granddaughters of farmers who went away and then felt the tug of the land and did an about-face. On Sobre Vista Road—a short distance, as the crow flies, from Green String—Ross grows year-round. He and his dad respect one another and keep a comfortable distance.

Fifty or so locals subscribe to Ross’ CSA. Once a week, they receive a box with goodies which they pick up at the Tasting House for Sixteen 600 Winery in Sonoma, where they can visit with wine maven, Sam Coturri, and purchase excellent grenache and cabernet from local, organic grapes.

Ross provides vegetables to Chez Panisse, the Berkeley restaurant founded by Alice Waters, who has done more than any other chef in America to educate the public about local produce and healthy food. On a Monday morning when I visited Ross, two women, both bartenders at Chez, were planting thousands of onions in a field bathed in sunlight. Kayla and Sydney belong to what might be called the bartending-to-outdoors movement. Sydney says, “I’ve learned how hard farming is and how much planning is involved.”

Ross looks away from the onions he’s planting. “Farming goes in cycles,” he tells me. “Until the 1940s, small farms were the norm around here. Then, Big Ag arrived. Now the pendulum is swinging back. The small farm movement is growing again all around the world.”

And close to home, too.

The “Farmily”

Flatbed Farm in Glen Ellen on Highway 12, a mere 1.8 miles from Oak Hill, is operated by three women who call themselves “a farmily.” Sofie Dolan owns the farm with her husband, Chris, the co-founder, and with his cousin, Matthew, the executive chef at 25 Lusk, which is one of my favorite San Francisco restaurants. Once, Lusk took much of the produce Flatbed had to offer. Now, the produce is mostly sold on Saturdays, from 9am to 3pm, to loyal locals who shop as though it’s part of their religion.

“We have a series of monthly outdoor workshops to educate people on how to garden on their own,” Sofie says.

Her family members were farmers in Sweden. She still remembers “Hostbeck”—that’s the name of the farm—the land, the hayloft and the chicken coop. “We’ve tried to recreate some of Hostbeck here,” she says.

Hayley, from Maine, has long felt passionate about plants. She’s the farm manager during the day and in the evening a waitress at Salt & Stone on Highway 12 in Kenwood—which features local mushrooms, oysters from Drake’s Estero and Atlantic lobster.

“During the pandemic, Flatbed has been my sanctuary and my pride,” Hayley tells me. “I talk to the plants and play classical music for them.” She pauses a moment and adds, “One of the silver linings of the pandemic is that it has brought the farming community closer together than ever before. We have reached out one to another, shared seeds and did trouble shooting together.”

Hayley is helping to educate customers about companion planting. She’s also putting into practice things she learned at school. “I belong to a network of women farmers who are also mothers,” she tells me. “We embrace Mother Nature and have a sense of acceptance about the rhythms and cycles of farming.”

Amie Pfeifer writes the Flatbed newsletter, which includes recipes for meals that are “fast, healthy and delicious.” She also runs the Flatbed store, which sells produce, flowers and “value-added products” like preserves and pickles. Amie grew up on a farm in Nebraska which once depended on manual labor, but is now “industrialized” and grows GMO corn. “I got out of unhealthy and into health,” Amie tells me. “If you want to be happy, don’t take a pill, go to a farm or to a farmers’ market.”

It’s time to head to Flatbed, where you can buy vegetable starts and meet the “farmily.” Hayley, Amie and Sofie would like nothing better. Erase the blues. Turn over the soil and grow your own. You might find it addicting.