In a profitable twist of fate, a private construction company is selling $98,000 worth of redwood trees to a public agency, largely from public land.

Last December, Ghilotti Construction was awarded a $30.5 million contract to replace the Airport Boulevard overpass along Highway 101, according to Caltrans’ website. The overpass will include new, longer on- and offramps, one of which will extend over Mark West Creek, and will result in the permanent closure of ramps just south at Fulton Road.

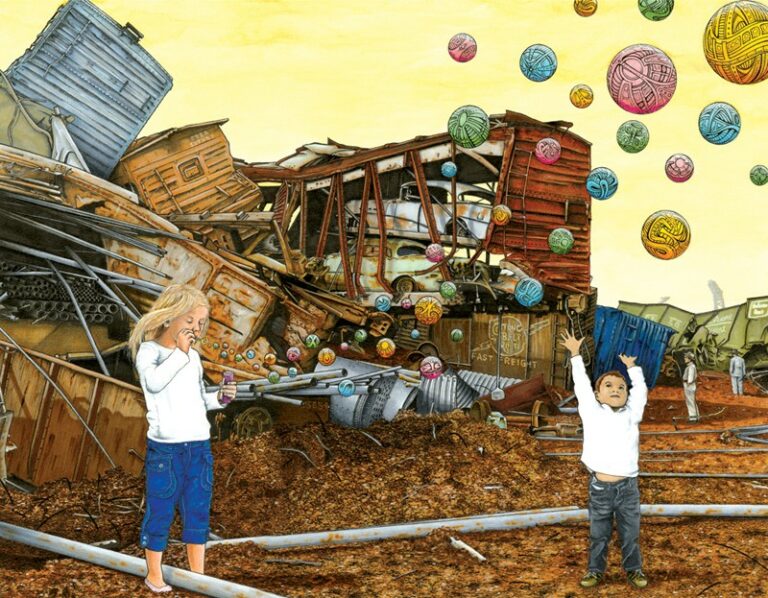

The project requires the removal of roughly 600 trees, underway now. With Ghilotti subcontractor Atlas Tree Service on site, stumps and bare logs now take the place of the redwoods, visible to motorists on the road.

Like so many of the redwoods along the northern corridor, these were non-native trees planted for aesthetic reasons decades ago in the early stages of the freeway’s construction. According to the project’s EIR, the redwoods “reinforce motorists’ perception of the regional landscape character and Highway 101 as the ‘Redwood Highway.'”

Many of the trees towered on land in Caltrans’ existing right-of-way, according to documents on Sonoma County Transportation Authority’s website. Highly detailed maps from a 2001 project study report show state right-of-way as a dotted line extending several feet beyond Highway 101’s border on either side, and stretching around the circular on- and offramps of both the Fulton and Airport overpasses. The majority of redwoods being felled are in grassy islands inside these snaking ramps.

Strangely, Ghilotti assumes possession of the valuable trees once cut down. In fact, the Sonoma County Water Agency is buying 200 logs from Ghilotti at the aforementioned cost of $98,000, according to SCWA spokesperson Brad Sherwood. The logs will provide structural enhancements along Dry Creek, which will be widened and shaped to benefit endangered coho and steelhead as part of ongoing improvements.

That’s a selling price of $490 a log—a cost that Sherwood says is fair value lumber price.

“Thirty-foot logs go for anywhere from $400 to $500,” he says. “The logs we’re purchasing are anywhere from 20 to 30 feet.”

Still, how can the property of a public entity be ceded to a private corporation and then sold to another public agency for a profit, with taxpayer money on both ends?

Kevin Howze, an engineer with the county’s department of planning and public works, has worked alongside staff from the Sonoma County Transportation Authority and Caltrans on the Airport Boulevard project. He says he isn’t aware of the details of this particular lumber transfer, but adds that it isn’t unprecedented.

“It’s not uncommon that debris can be the contractor’s responsibility,” he says. “Sometimes it has value; other times it’s nothing more than a nuisance.”

[page]

When asked if the deal could be complicated by the fact that many of the trees are on public state land and being sold—by a private company—to a public county agency, Howze responded that though unusual, “there’s nothing inherently wrong with it.”

“It was explained to me that Ghilotti is contracted with Caltrans to clear the site,” Sherwood says, adding that he, too, asked how the trees became the contractor’s property when he heard about the deal, and that county contractors and legal counsel were contacted to ensure this was standard practice. “As part of that responsibility,” he says, “they essentially own whatever’s on the site.”

Ghilotti did not return a call seeking comment.

As redwoods from the state right-of-way are being sold to the SCWA, a plot of land between the two onramps that was designated as county open space is also going away to Caltrans for construction. A document from the Transportation and Public Works board meeting dated March 20, 2012, details the transfer, which includes two parcels of land in a 610-foot strip near Mark West Creek.

“The Specific Plan for the Sonoma County Airport Industrial Area, dated July 13, 1987, designates a portion of the subject property as a riparian conservation and enhancement corridor,” the document reads. “The State’s proposed use of the subject property as a freeway project is clearly incompatible with the Specific Plan designation.”

However, the document concludes, Caltrans would likely seize the property via eminent domain for the freeway widening project if the county agency attempted to hold on to it. The open space land was ultimately offered to the state via a possession and use agreement, which stipulates that Caltrans “make its best efforts to convey easements to the County over the subject property and other adjoining land in the vicinity for future public access purposes.”

One of these uses will ideally be a pathway near the creek that runs under the freeway. In the county’s 2010 general plan, a multi-use pathway is called for the site, running between Old Redwood Highway and the SMART railroad tracks, similar to the Prince Memorial Greenway along Santa Rosa Creek. As it stands now, the county will have to hope Caltrans operates in good faith to allow the county usage of the former open space land.

“If we went to court, we would just get money, so hopefully we’ll still have something we can negotiate with,” says Eric Nelson, an agent with the Transportation and Public Works Department. He points out that this piece of land isn’t unique; it’s one of many being used by Caltrans for the widening project, part of the Highway 101 congestion relief program begun in 2004 (or, as local bumper stickers once famously declared, “Three Lanes All the Way”).

Though concern has arisen over the highly visible redwood removal along the freeway in Petaluma, Nelson says he hasn’t heard any protest about the Airport- and Fulton-area trees from local conservation groups.

“As to the ugliness of taking down the redwoods, we haven’t really had an oar in that water,” says Steve Birdlebough, chair of the local Sierra Club chapter. “Maybe we should have. That’s when the chickens come home to roost for a lot of folks. It’s the final realization of ‘Oh dear me, what have we done?'”

Most of the Sierra Club’s efforts were in the EIR stage of the 101 expansion, Birdlebough says, ensuring that HOV lanes to encourage carpooling were part of the mix.

“In the ’70s and ’80s, the Sierra Club’s concern was much about visual scenery,” he says. “In the ’90s and ’00s, our concern has turned toward the question of climate disruption and use of fossil fuels, of changes so serious we humans may not be able to adapt fast enough.”

Perhaps not. But in the meantime, freeways expand, trees turn a nice profit, and the “Redwood Highway” is becoming ever more a misnomer.