As Shakespeare once wrote, “Summer’s lease hath all too short a date,” which is a fancy way of saying enjoy the good weather while we have it—and for some of us, that means escaping to the mountains for a bit of scenery, sun-screen and Shakespeare.

Though the Oregon Shakespeare Festival has technically been running since February, summer is the time of year when folks from all over the country—including a huge number from the North Bay—make the trek up over the Siskiyou Pass and down into the impossibly charming town of Ashland, Ore. In June, when the vast outdoor Elizabethan Theatre opens, along with three new productions, the total number of shows playing in repertory is nine. Two more will be added in July, and one (August Wilson’s Two Trains Running) will end, but this is the time of year when the most shows are happening all at once—and the audiences begin to arrive in droves.

Why?

Because the Oregon Shakespeare Festival is, quite simply, one of the finest repertory companies in the world, and their productions employ some of the best actors and directors in the business—not that the occasional onstage misfire doesn’t occur. It does. And this year, there are a couple. There are also a handful of productions that rank as the best I’ve ever seen.

Here are my views of the OSF shows currently running.

‘KING LEAR’ (Thomas Theatre) ★★★★★

It can be risky bringing new ideas to plays that are universally well-known, jarring audiences out of fond expectations. In Bill Rauch’s intense, relentlessly paced take on Shakespeare’s King Lear (through Nov. 3), the risks pay off big time, resulting in what is the best, most entertaining, upsetting, unsettling, thrilling and deeply moving Lear I’ve ever seen—and frankly, I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve seen this soaring tragedy.

But I’ve never seen it like this.

Staged in the round within the intimate Thomas Theatre, director Rauch sets the play in modern times with echoes of past generations hanging over it. King Lear, easily the lit world’s most heartbreakingly foolish monarch ever—and one of the theater world’s most demanding roles of all time—is played on alternating nights by two different actors, Jack Willis and Michael Winter, possibly to give each other time to rest up for the next emotionally grueling show.

At the start of the show, Lear is ready for retirement. Fond of the perks of being king but ready to relinquish the responsibilities of leadership, he goes against the counsel of his advisers, and offers to split his kingdom into three, giving rule to each of his daughters, Goneril (Vilma Silva), Regan (Robin Goodrin Nordli) and Cordelia (Sofia Jean Gomez).

Almost immediately things go badly, and hints of Lear’s coming dementia are spied by his daughters, with Lear promising the largest holding to whichever of them can testify to loving him most. When Cordelia, honest to a fault, refuses to play the game, she is disinherited, and Lear’s kingdom is divided between Goneril and Regan.

For the following three breathtaking hours, told over three full acts with two intermissions, the breaking of Lear’s kingdom continues, everything crumbling into small and smaller pieces, along with his sanity, as the daughters, and their husbands, cheat, lie, conspire, seduce and murder their way deeper and deeper into war, madness and ruin. The pace never slackens, and the inventiveness with which Rauch brings fresh ideas and visuals to the story never wanes.

The cast is marvelous, committing body and soul to the ensuing mayhem, and the aching, poisoned hearts of these all-too-human characters are always in view. No matter how brutal or bloody the action, Rauch keeps King Lear grounded in stark, brave believability.

It may leave audiences shaken, but its goal is to move us and make us willing to examine the wise and unwise choices we all make, to question the motivations behind every word of flattery and compliment, and to see the broken hearts behind every human cruelty.

‘THE UNFORTUNATES’ (Thomas Theatre) ★★★★½

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s commitment to original work has produced a number of plays that have gone on to become huge successes elsewhere. I predict the same road lies ahead for a smart, uncategorizable new musical that has proven to be one of this year’s biggest hits.

Directed by Shana Cooper, The Unfortunates (though Nov. 2), by the hip-hop team 3 Blind Mice and playwright Kristofer Diaz, was developed through a series of workshops and late-night sneak peeks. Occasionally baffling, but mesmerizing and deeply moving, The Unfortunates is a theatrical fantasia on the themes and characters from the American blues song “The St. James Infirmary Blues.” Layering elements from the seminal folk ballad “The Unfortunate Rake,” the musical begins with a group of soldiers waiting for execution, one of whom finds himself transported into the world of the song the soldiers have been singing as they await their fates.

The visuals are gorgeously strange (Tim Burton strange), and the songs combine blues, rap, folk and rock to create a truly original, weirdly satisfying piece of musical theater. There have been countless variations of “The St. James Infirmary Blues,” in which a dying young man tells the story of the woman who “cut him down” in his prime. The song, in various forms, has been covered by everyone from Cab Calloway to the Doors to the White Stripes, and has been referenced in a famous Betty Boop cartoon, countless books and movies, and even a few old cowboy laments.

As the doomed soldier, Joe (Ian Merrigan) is transported into the song, he becomes Big Joe, the fighter with enormous fists, in love with the armless prostitute Rae (Kjerstine Rose Anderson), whom he cannot help, even with his skills as a fighter and gambler. The plague is raging, and St. James Infirmary is the only hope, with the doctors’ offer of a cure—for a price. The dreamlike qualities of the play are brilliantly created with some strong stagecraft, resulting in one of the most memorable and emotionally complex plays of the season.

[page]

‘THE TAMING OF THE SHREW’ (Angus Bowmer Theatre) ★★★★½

The Taming of the Shrew, one of the trickier Shakespeare shows to present to modern audiences, has been given the Beach Boardwalk treatment by director David Ivers, with a rockabilly soundtrack that makes the show—and it’s love-and-war attitude—not only palatable, but actually kind of sweet and infectious.

Kate (Nell Geisslinger), is the wild-child outsider of her family, who own a great deal of the Beach Front Boardwalk of Padua, with a roller coaster and Ferris wheel hovering over the impressive set. When Petruchio (Ted Deasy) arrives, the tattooed, guitar-strumming charmer from out of town quickly falls for Kate, in whom he recognizes a kindred soul, an outcast marching to her own drummer, much like himself. When her father agrees to marry her off to Petruchio, she rebels, vowing to make Petruchio’s life a living hell, until Petruchio, played with far more heart and sweetness than in most productions, decides to tame her using the only means he can think of, which is basically to act crazier and more out-of-control than she is.

The less acceptable parts of Shakespeare’s story, where Petruchio keeps Kate hungry, sleep-deprived and off-balance, saying it’s all because he loves her too much to allow her to eat food that isn’t as perfect as she—that stuff actually works here, because for once the show is played as a true romantic comedy, with a Petruchio and a Kate that we really hope end up together, happy at last. Geisslinger and Deasy have amazing chemistry together, and watching them fall in love, in fits and starts, is like a special effect unto itself, with the road to romance entertainingly rocky, right up to the final rock-and-roll-fueled climax.

‘MY FAIR LADY’ (Angus Bowmer Theatre) ★★★★★

Whether by design or by accident, OSF has paired one of the best Taming of the Shrews I’ve ever seen with the only production of My Fair Lady (through Nov. 3)—arguably a Victorian spin on Shrew—that hasn’t made me squirm with discomfort.

The play that inspired the Lerner and Loewe musical, George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, was trying to make a point about the unfairness of class distinction. Still, it carries the underlying suggestion that, way down deep, women like being bullied by men.

Henry Higgins (Jonathan Haugen) is a curmudgeonly expert in linguistics, who encounters a lower-class flower girl named Eliza Doolittle (Rachael Warren), and takes her on as a student, all to prove that the only thing separating the poor folks from the rich folks, aside from money, is the way they speak.

Shaw, in creating the characters of Higgins and Eliza, shook things up in a big way, challenging long-held assumptions about class and humanity. But then he cavalierly wallpapers the show with misogynist one-liners that seem to be more than just a comment on Higgins’ uncouth attitude. They seem to be inside jokes that all men will get a good laugh from.

In the musical version, which actually adds a happy ending for these two, the misogyny only gets worse. For Eliza to end up with this unfeeling, selfish, narcissistic, borderline sociopath is a tragedy, a disaster of epic proportions, for Eliza anyway.

That’s why I don’t like My Fair Lady.

So why do I love director Amanda Dehnert’s sleek OSF version? For one thing, Dehnert is a genius. Understanding the problems plaguing the play, not content to merely stage it with pretty costumes and say, “Oh well, that was a different time,” Dehnert has virtually rewritten the play from the inside out—without changing a single line.

The play begins when the doors open for the audience, two grand pianos at the center of the stage surrounded by racks of costumes, piles of props, several actors already present, stretching, warming their voices and chatting with each other. At the top of the show, actress Warren, not yet in character as Eliza, starts up a conversation with the audience, then produces her own cell phone, switches it off, and hides it beneath a bank of lights because, as she says, “I have to do this show now.”

And suddenly, accompanied by just two pianos and the occasional cast member fiddling a few licks when appropriate, My Fair Lady begins, resembling a rehearsal more than a performance, with the cast all sitting onstage in a ramshackle set of chairs, watching the play themselves until called upon to don a costume and take part.

The effect is powerful and immediate.

Without sacrificing a bit of the charm of the characters or the music, it is clear that this is a game, and everyone knows it. That right there might have been enough, but the performances of Warren and Haugen, under Dehnert’s delicate direction, reveal full-fledged human beings beneath the skin of these people. Eliza is allowed to be more than a screeching joke at the beginning and a simpering codependent at the end, and Higgins is amazing, a narcissistic bully who behaves the way he does because no one has ever forced him to grow up.

Eliza does force him to, and by the end of the play, each is warier and wiser, and when they come together in the final seconds of the play, which Dehnert allows to happen in the audience, away from the stage where their game has been played, they come together in a way I’d have thought impossible for My Fair Lady: as true equals, each recognizing the strengths and weaknesses in themselves and each other.

‘TWO TRAINS RUNNING’ (Angus Bowmer Theatre) ★★★★★

The late American playwright August Wilson, over the course of 25 years, wrote 10 plays unofficially called “the Century Cycle,” since each takes place in a different decade of the 20th century. Two Trains Running (though July 7), which Wilson wrote in 1991, is his ’60s play, taking place just over a year after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. inside the rundown Hill district coffee shop of self-made man Memphis (Terry Bellamy, magnificent).

The play covers a few days in the lives of the folks who’ve made Memphis’ diner the hub of their existence. These are potently rich, real characters, flawed, frail and fleshed-out, from Wolf (Kenajuan Bentley), the flashy numbers runner who seems to be the only one making any money, and no-nonsense waitress Risa (Bakesta King, marvelously fierce and frail), whose practiced detachment masks a fierce sense of sadness, to recent parolee Sterling (OSF mainstay Kevin Kennerly), just looking for a break, and Hambone (an excellent Tyrone Wilson), the developmentally disabled man-child whom Risa gives free meals to. In many ways, Hambone—with his plaintive, oft-repeated cry “I want my ham!”— is the heart of the play, steadfastly insisting on getting what was once promised him, in exchange for painting a white grocer’s fence 10 years before.

Directed with loving detail and a strong sense of character by Lou Bellamy—who’s directed more of Wilson’s plays than any other director on the planet—this is a great one for first-timers to Wilson’s world. Arguably the most hopeful of his 10 plays, Two Trains Running is a generous play, distributing with lumpy impartiality a whole series of happy and semi-happy endings among its characters—characters that live such frustrated and hopeful lives, it is impossible not to want them to get everything they deserve, from ham to happiness, from a fair break to lasting love.

[page]

‘A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM’ (Elizabethan Stage) ★★½

The big disappointment of the season is A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Christopher Liam Moore’s poorly thought-out staging of one of Shakespeare’s best known and most loved comedies. Though the visual look of the show is stunning, with leafy green projections employed to make the ramps and swirls of the wooden stage look like a vibrant forest, the whole enterprise feels forced and clunky, careening between scenes that are dull and lifeless, and others so badly constructed they look like something improvised in a high school drama class.

On top of that, Moore jettisons Shakespeare’s text frequently, replacing names, titles and exposition with his own material, all to accommodate his resetting the play to 1964, on and around a Catholic college. I have no problem with shifting the setting of Shakespeare’s plays. To my mind, you can set them in the past, present or future, plop the characters down in the Depression, the Apocalypse or on the planet Krypton. But if you have to change the text to fit the vision, you need a different vision.

By comparison, My Fair Lady managed a triumphant reimagining without altering any of the words at all. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, it happens often, and usually to the detriment of the story. The bad ideas begin with Moore’s decision to transform the soon-to-be-married warrior Theseus and his Amazon queen conquest Hippolyta into priest and nun—Father Theseus and Sister Hippolyta—who shock everyone, but not enough (given that it’s 1964), with their decision to marry.

The primary story deals with the merged antics of four young lovers, escaped to the forest, the warring magic of two bands of fairies and a troupe of actors using the woods to rehearse a play. In this version, the actors are staff from the school, requiring the original’s Snug the Joiner to become Snug the Janitor. The foolish Bottom, the one who famously ends up transformed into a half-donkey, is the school’s PE teacher.

One gets the idea that it almost might have worked. But it doesn’t, and the actors appear to know this. With only a few exceptions, the performances are tentative, wooden and flat, the performers sounding as if they are reciting text rather than uttering words coming from their souls and minds, an additional insult given the lighthearted lusciousness of the text.

‘CYMBELINE’ (Elizabethan Stage) ★★★½

When Shakespeare first wrote it, Cymbeline (running through Oct. 13) was a blockbuster. But today, it has become trendy to disregard Cymbeline as an unsatisfying and seriously messed-up play. It is certainly a bit of a mash-up, as if Shakespeare had collected piles of random ideas and then, toward the end of his career, tried to cram them all into one play, whether they fit together or not. That would explain the wildly careening shifts in tone—from comedy to tragedy to satire—and such odd elements as princes disguised as acrobatic mountain men and a headless body mistaken for someone else.

Still, I’ve always loved Cymbeline, with its pre–Brothers Grimm tropes of an evil stepmother, a pure-hearted princess who’s escaped to the woods, benevolent spirits and other supernatural forces arriving in time to make everything right. In this visually stunning production by Bill Rauch (who also directed King Lear), those occasional fairy-tale elements inspire a production packed with elves, orcs and guys with horns, casually interacting with each other as if they were a band of characters in a game of Dungeons and Dragons. Walt Disney movies are an obvious influence as well, the evil stepmother dressed to resemble Snow White’s sorceress queen, complete with a steaming cauldron and poisoned apple.

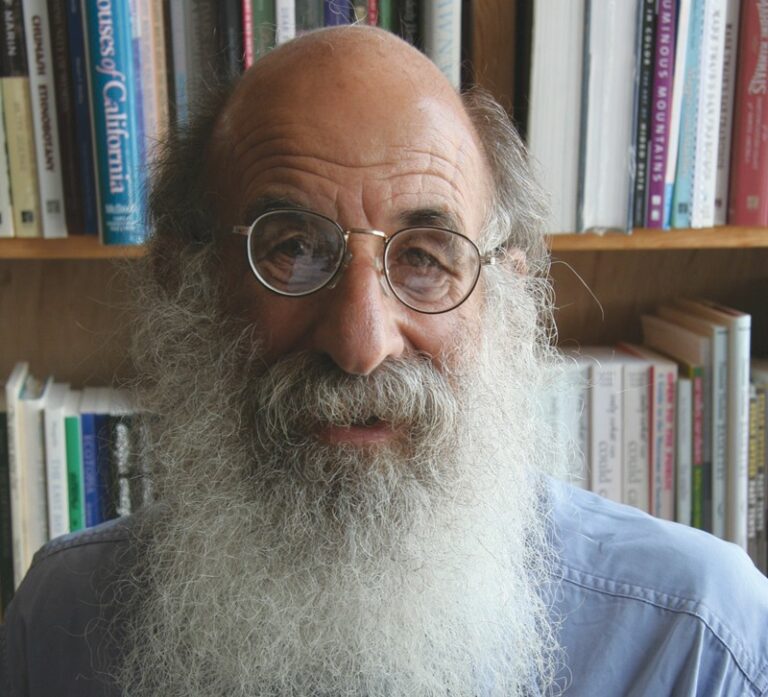

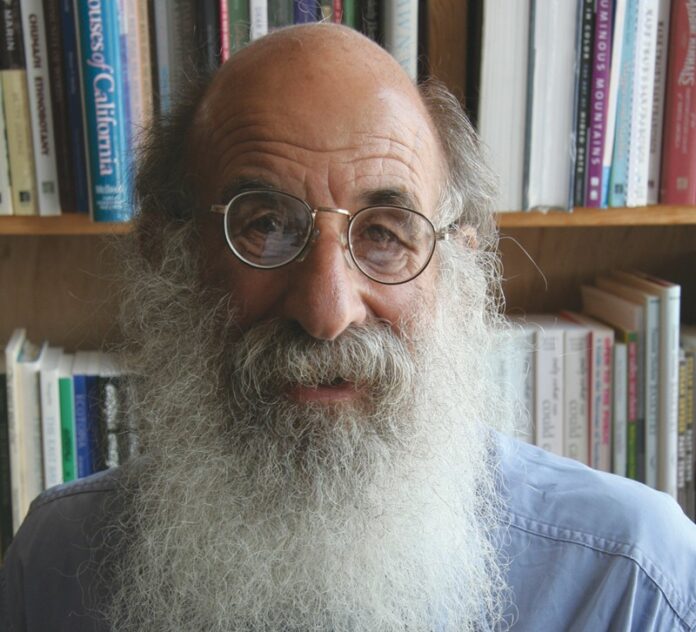

Those elements, unfortunately, prove more distracting than illuminating, and as much as I love elves, orcs and guys in horns, they feel forced, superimposed onto the story rather than integrated into it. Which is a shame, because everything else works. Cymbeline, a pagan king who’s fallen under the spell of his heartless but beautiful second-wife, is played with fragile power by the great American actor Howie Seago (look him up on Wikipedia), who just happens to be deaf.

In casting a deaf actor, who speaks here in sign language and the occasional impassioned wordless cry, Rauch uncovers a number of rich dramatic textures. Watching the other characters approach to signing, for one thing, reveals more about their characters, and their feelings for the king, than they make clear in their words.

The primary story, a tangent-filled epic of lost loves, lost children, lost sanity and lost plot threads, is entertainingly and clearly told, with plenty of gorgeous stage magic to keep the eyes dazzled, even when the brain gets a little overworked. Rauch keeps the tone light, even during the heavy parts—and especially during the headless parts—and allows the actors to poke fun at the story they’re engaged in, essentially winking at the audience, agreeing that it’s all a bit much.

While I definitely do recommend Cymbeline, I personally would have preferred less of that knowing jokiness. We don’t need to be reminded that it’s a bit silly. The guy with the horns made that clear from the beginning.

‘THE HEART OF ROBIN HOOD’ (Elizabethan Stage) ★★★★

While much of Shakespeare’s appeal is his incomparable use of language, it is writer David Farr’s understanding of action and twisty-turny plotting that drives The Heart of Robin Hood, an entertaining origin story unfolding on the Elizabethan stage. Easily the best show of the new outdoor openings, this Robin Hood reframes the myth from the point of view of Maid Marian (an eclectic and delightful Kate Hurster), who encounters the famous thief (played with goofball relish by John Tufts) when she escapes to the woods to avoid marrying the evil Prince John (an amazing Michael Elich).

The idea here is that, before Marian, Robin Hood was just a dim-witted thug, stealing from the rich—and keeping the loot. It is only when he begins to take responsibility for the lives of a group of orphaned children that Robin begins to feel a sense of obligation for the fate of others. As he gradually warms to the idea, his fellow thieves come on board as well, embracing the shocking notion of actually doing good for others.

The language is rich and funny, but the strongest Bard-light comparisons are in the Elizabethan-style plot, complete with Marian donning a boy’s costume to join the Merry Men (a device also seen in Cymbeline, and many other Shakespeare plays).

Seago appears here again, this time as Little John, and his giddy, full-hearted performance matches those of the rest of the cast. The story is fast-paced, crammed with visual spectacle (and some awesome stage fighting), and even genuinely moving, as Marian discovers her own true vocation while, almost by accident, teaching Robin Hood where his own heart lies.