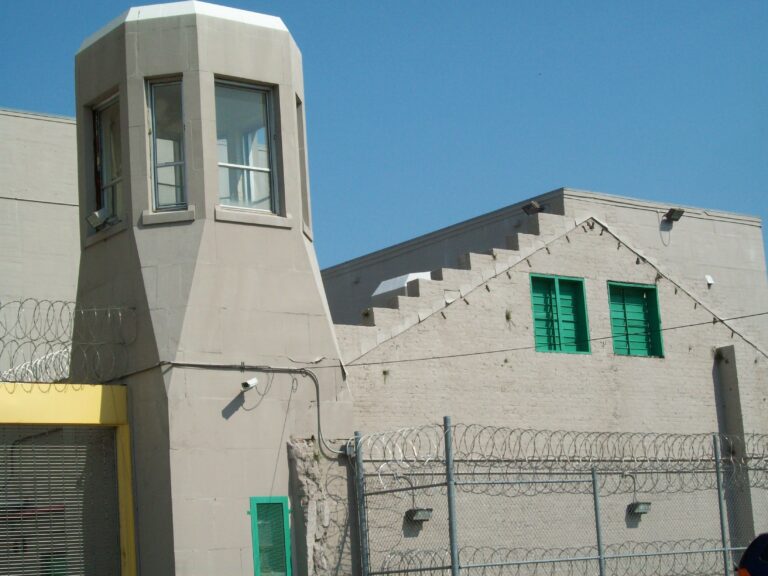

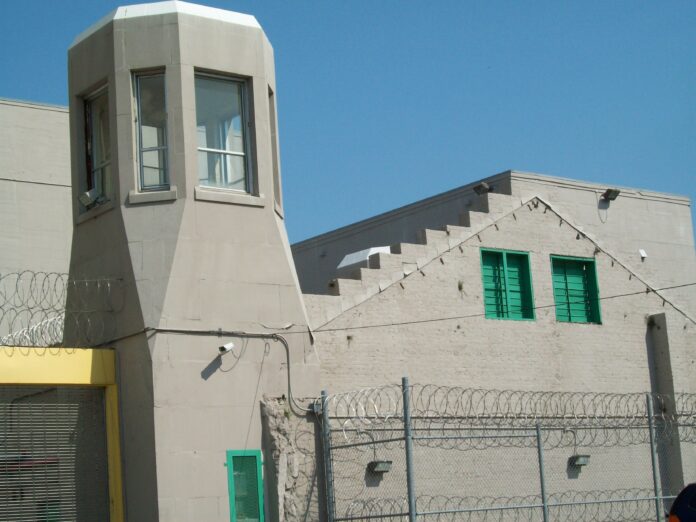

Rhonda Jean Everson was a 50-year-old addict when she died in custody in October 2014 at the Sonoma County Main Adult Detention Facility, the main county lockup that houses some 800 inmates on any given day. Everson died shortly after being arrested on drug charges and outstanding felony warrants for prior shoplifting offenses, according to police records. Her family claimed at the time, in social media posts, that Everson was refused medical attention over the course of her incarceration at the MADF—a stay that ended when she was found dead in a cell by a nurse and corrections guard who had arrived, according to the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office, to administer unspecified medications. And according to court records, Everson died just a couple of months after a civil rights lawsuit she filed against Sonoma County, Santa Rosa and Sonoma County Health Services director Rita Scardaci was dismissed in federal court.

How did Rhonda Everson die? Was her death preventable? These questions have hung in the air since 2014, as Everson’s death was one of three at the Sonoma County jail over a period of three short weeks that year; one of them was a suicide. The questions were raised all over again after a highly damning report about the jail was released last week.

Where was Everson located when she died? The county says she was not in what’s known as a “quiet cell” in the jail’s mental-health module utilized for disruptive inmates. The so-called quiet cells, it turns out, are a very rare occurrence among the half-dozen county lockups investigated by Disability Rights California (DRC) and the Prison Law Office, which last week highlighted Sonoma County’s mental-health problems at its local lockup in their report.

The cells are so rare, in fact, that, of the six jails investigated by DRC, which included facilities in Sacramento and Santa Barbara, Sonoma County is the only lockup that uses them. Among other findings, the DRC was heavily critical of those quiet cells in use at the jail. The county says that despite the report’s negative assessment of the facilities, it will continue to use them.

A little background. Mental-health services at the Sonoma County jail are provided by the Sonoma County Behavioral Health Division; medical treatment is provided by a private company called the California Forensic Medical Group. The DRC report homed in on the jail’s county-based mental-health providers. Among its numerous findings, the DRC highlighted what it called illegal practices around the involuntary injection of inmates with drugs when they are not on what are known as 72-hour mental-health involuntary holds (aka “5150” holds). The county denies any illegality and has defended its jailhouse medical protocols, even as it says it has ended one of the practices highlighted by DRC.

Inmates can only be injected against their will after a so-called court-sanctioned Riese hearing has been held, and the inmate is found, for example, to be at risk of harm to themselves or others.

As it found with the use of quiet cells, the Sonoma County lockup was the only one of the six investigated by DRC that injected inmates with long-term psychotropic drugs without a court order. The county says it stopped doing that before the DRC report was issued.

The DRC report also criticized the jail for overuse of solitary confinement for its mentally ill inmates.

Did the report do anything to shed light on Rhonda Everson’s death? In late October 2014, just days after Everson was found in her cell, the sheriff’s office posted a statement on Facebook which said that the “circumstances surrounding Everson’s death are unclear.” The statement goes on to say that Everson died “in a special housing unit with a focus on inmates going through withdrawal.”

What does that mean to be jailed in a cell that is focused on withdrawal? Unclear. But generally speaking, “special housing unit” is jailer longhand for “the SHU” which is itself jailer shorthand for “solitary confinement.” The DRC report has a main-through line critical of Sonoma County’s use of solitary-confinement to deal with an ever-expanding population of mentally ill prisoners. And addiction is considered to be a mental-health issue as much as a physical-health one. Yet the county insists that Everson was not in a quiet cell at the time of her death.

The sheriff’s office description of Everson’s cell may have raised more questions than it answered. What does a solitary confinement cell for an inmate going through withdrawal look like? Where is it located? Are there regular visits from medical staff?

Capt. John Naiman of the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Department sent the following statement to The Bohemian in response to questions about the circumstances around Everson’s death: “I’m unable to provide specific information about Rhonda Everson because of pending litigation. I do believe there is some general information I can provide to assist you in understanding the various housing units located within the Sonoma County Main Adult Detention Facility. Inmates who are at risk of going through withdrawal symptoms from drugs or alcohol are generally housed in R-Module. Because of its location and design R-Module is particularly well suited to housing inmates who are at risk of withdrawing from drugs or alcohol. R-Module is a short walk from the Booking intake area and provides easier access to the court holding areas than other housing modules. Being a single level unit, inmates who are at risk of withdrawing do not have to walk up or down stairs to get to their cells or access features of the module such as phones, televisions, showers, or visiting. This is particularly important for someone who may be unsteady on their feet or suffer from mobility issues.

Inmates who are at risk of going through withdrawals are typically assigned a single occupancy cell. This is particularly important for those inmates who have symptoms of gastrointestinal upset, nausea, vomiting, headaches, anxiety, or in more severe cases delirium or hallucinations. R-Module was originally designed as a general population housing module and the cells were designed accordingly. Recently the R-Module dayroom was remodeled to allow inmates of different classifications to have out of cell activity time in secure sub dayrooms. This was an important modification to maximize out of cell time for inmates of all classifications. Each cell has an emergency call button inmates may push to summon a Correctional Deputy in case of an emergency. In addition to housing inmates at risk of withdrawal, R-Module can also house general population inmates as needed.

There are no Safety Cells in R-Module. If an inmate were to become actively suicidal they would be moved out of R-module and rehoused to a Safety Cell located in other areas of the facility.”

The “safety cells” are padded solitary confinement cells in use at the Sonoma lockup. As for the quiet cells, the DRC report says the quiet cells are located in the jail’s Mental Health Module and that “staff appeared to be using these cells for people who were disruptive due to their mental-health symptoms.”

According to the DRC report, the cells are constructed so that staff have to unlock two doors to reach the inmate. The apparent purpose of the cells is to ensure that other inmates and staff don’t have to listen to the cries and screams, but the county highlights the cells’ “therapeutic” value for certain inmates with mental-health issues.

If the DRC characterization is accurate, this double-down lockdown of inmates engaging in disruptive behavior for “therapeutic” purposes is something you’d expect to see at, say, San Quentin’s death row Adjustment Center, the jail-within-a-jail for the hardest of the hardcore killers and psychos in the state. It’s not the sort of thing you’d expect to find at a county lockup filled with comparatively low-level offenders such as Rhonda Everson.

As described by the DRC report, whatever their benign-sounding name, quiet cells are intensely isolating: “Unlike the other cells in this unit, individuals cannot view the dayroom through their cell window, and staff also cannot see them from the dayroom. They cannot hear other people inside the unit, and staff also cannot hear them.”

The DRC report is clear on the point that a jail that uses quiet cells is asking for trouble. “This practice creates isolation within isolation and may worsen their psychiatric conditions,” the report notes. “It also significantly increases the risk of suicide.”

Deputy county counsel Joshua A. Myers says the jail continues to use the quiet cells despite the DRC’s warnings about them. He adds that Everson was not housed in a quiet cell. In an email, Myers pushed back against the DRC’s characterization of the cells.

“They are not ‘isolation’ cells,” Myers writes. “Quiet cells serve a therapeutic purpose for certain inmates. Ms. Everson was not housed in a quiet cell at the time of her death.”

Myers adds that an autopsy on Everson was done by the Marin County Coroner’s Office, “and the Sheriff’s Office conducted its own investigation.” He did not provide the results of either investigation.

[page]

An Everson family member emailed theBohemian this week to say that they have an attorney who is looking into the circumstances around Rhonda’s death.

Sonoma County has meanwhile carved out an aggressively legalistic posture in relation to the most damning of the DRC charges, and is denying any illegal activities around its inmate-injecting policies, even as it agreed to end the practice of injecting inmates with long-term psychotropic medications in the absence of an involuntary mental-health hold, which the DRC insisted it do.

Myers says the Behavioral Health Department “had already taken the initiative to revise its policies around the use of long-acting psychotropic medications before the release of the DRC report,” and adds that, “the change identified in the DRC report was driven by an interest to continually assess and improve Behavioral Health’s clinical practices.”

The county’s positioning is unsurprising, given that the DRC report concludes that “there is probable cause to conclude that there is abuse and/or neglect of prisoners with disabilities at the jail.” That also means that there is probable cause that Sonoma County may be faced with a lawsuit over what DRC charges is its illegal injecting of inmates at the MADF.

Sonoma County lawyers also attempted to undermine the DRC report by accusing inmates who spoke with the investigators of exaggerated claims of mistreatment. On that subject, Myers would only say that the county appreciated the investigators’ efforts.

“The Sheriff’s Office and Behavioral Health welcome the opportunity to work with [DRC] and the Prison Law Office on these issues,” writes Myers. “The Sheriff’s Office and Behavioral Health have a longstanding commitment to providing the best possible mental-health treatment and care to its inmates. The Sheriff’s Office and Behavioral Health anticipate continuing to collaborate with the DRC in the future regarding the issues identified in the report.”

Anne Hadreas is a DRC attorney who was among the six lawyers and investigators who toured the jail last August; that tour coincided with the county signing off on a plan that same month that will see a new $48 million Behavioral Health Unit built on the jail campus by the end of 2020. The new facility is designed to ease the strain of mentally ill inmates that have flooded the jail.

But 2020 is a long ways off, and DRC says the county has to act now, especially given its findings: the terrible clinical conditions that don’t lend themselves to proper mental-health treatment; the illegal injecting of inmates; and the benign-sounding quiet rooms identified as anything but by the DRC report.

The report arrived amid persistent criticism of the Sonoma County jail for failing to keep up with the needs of a rapidly changing prisoner population, a sizable portion of whom arrive at the jail with already-prescribed psychiatric needs.

Against that backdrop, county leaders and lawyers wasted no time in telling the Press Democrat last week what they thought “the real problem” was at the jail, following the release of the DRC report. It’s not the illegal doping of prisoners or the inhumane solitary-confinement cells in regular use or the compromised therapy sessions conducted through a closed door.

The real problem identified by county leaders is a mental-health crisis in a state that has de-institutionalized the mentally ill without providing adequate backstop in the form of community or volunteer-based programs and settings. It’s a fair enough argument, as far as it goes, but DRC says it doesn’t get the county off the hook for the legal and ethical issues at MADF. And it’s notable that county leaders made that argument even as Sonoma County supervisors voted 5–0 against a proposed drug-treatment center near Bodega.

It is not news to report that Gov. Jerry Brown’s much-criticized realignment plan, which shoveled thousands of low-risk offenders from the state prison system into county lockups, coupled with a decades-long policy of deinstitutionalization that hasn’t been met with a buildup in community-based treatment facilities, has turned jails into de facto psychiatric hospitals.

Sonoma County is not alone in dealing with the ensuing crisis. After two unsuccessful tries, it secured state funds last year to build the new Behavioral Health Unit, a move that also reflects a new normal where jails act as a catch-all for a failed social-services net that has proved woefully inadequate to the needs of the mentally ill.

The DRC report urges that the MADF shortcomings need to be addressed now, with new solutions to deal with the crunch of mentally ill inmates. The jail can’t wait five years for the new unit. Jail staff, says Hadreas didn’t simply err in administering drugs to inmates without a proper court order—they did so without being able to rely on any of the necessary clinical features you might find in a proper mental-health unit located in a jail. Even when they did have the proper legal backing, she says, staff administered powerful drugs, including antipsychotics to troubled inmates, only to return inmates to solitary-confinement cells, where therapy sessions are conducted from chairs placed outside the cell. That’s not just less than ideal, DRC says; it’s completely counterproductive to any beneficial therapeutic end the county hopes to achieve.

“They are in an environment that’s not even a jail mental-health environment,” Hadreas says, “and they were not getting the higher level of care that comes part and parcel with the involuntary medication.

“If you are going to take away rights,” she adds, “you have a duty to give them a complete and appropriate treatment.”

Hadreas and the DRC report illuminate a real and potentially menacing Catch-22 for mentally ill inmates who wind up at the Sonoma County lockup: the jail is ill-equipped to work with those inmates in a proper clinical environment, so the inmates are warehoused in solitary-confinement cells, which creates more (and immediate) mental duress for them. This in turn requires that more drugs to be injected in order to sedate inmates and compensate for the ongoing decompensation wrought by the jail’s overuse of solitary confinement. And around it goes.

Hadreas says that regardless of outside forces not in its control, Sonoma County is ultimately responsible for the mental-health failings at the jail.

“I agree that it is very difficult, in terms of prison realignment and other budgetary issues, but my response is that it doesn’t get the county away from their duty to provide appropriate care, and sometimes we need to create systems to do that. It is very upsetting to see this.”