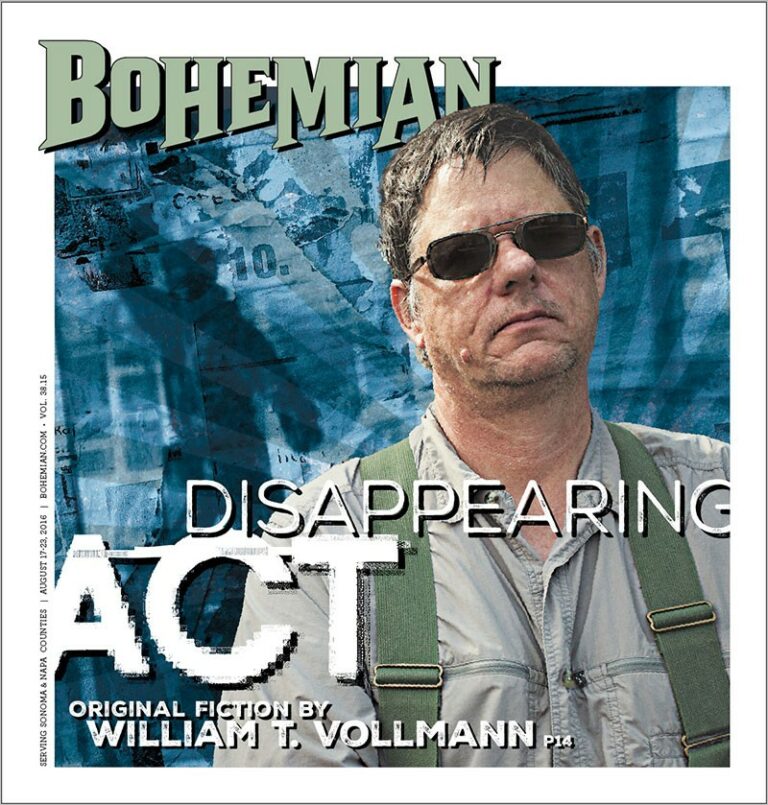

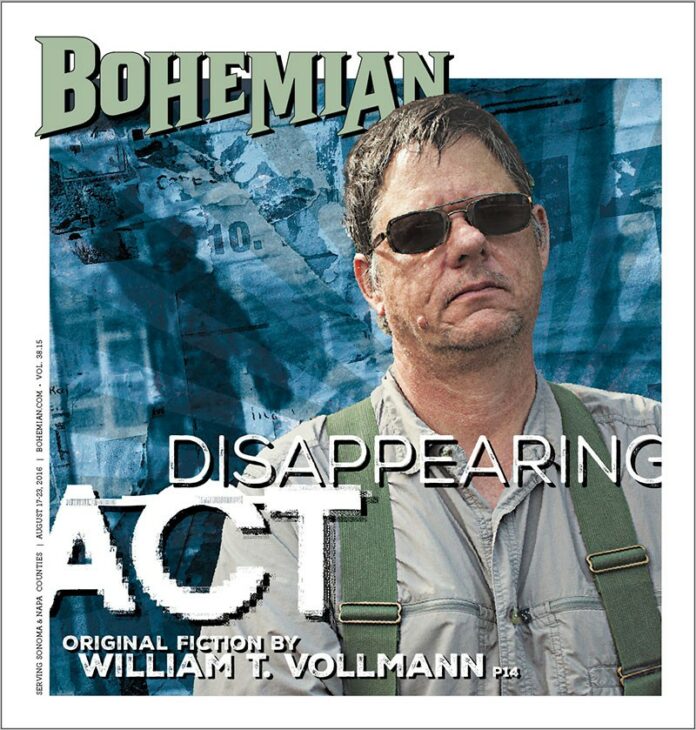

A few years after deciding to write a novel about a young man named Matthew who sets out to see America, I met Mr. Stett Holbrook of the Bohemian, with whom I contracted to deliver what we officially agreed would be a short piece about something or other. The only stipulation was that whatever I turned in show some relation to the Bohemian‘s area of readership. Since I live in Sacramento, I settled on Redding, which was not only a fairly straight shot north, but also virtually unknown to me.

In Sacramento, which can get plenty hot, some people smugly console themselves that at least we often get the famous Delta breeze, while poor Redding, etcetera, etcetera. The only information I had on Redding was from my local newspaper, which, as newspapers will, retailed accounts of drug busts and violent crimes. Thinking to follow up along those lines, I telephoned a Redding private eye, who, unlike all the others of his kind whom I have hired over the years, was gruff, suspicious and sullenly unhelpful. None of the other PIs returned my calls. I set out expecting to find a sweltering, downtrodden place. In fact, Redding was cool and green just then, and its inhabitants turned out to be some of the nicest people I have ever met.

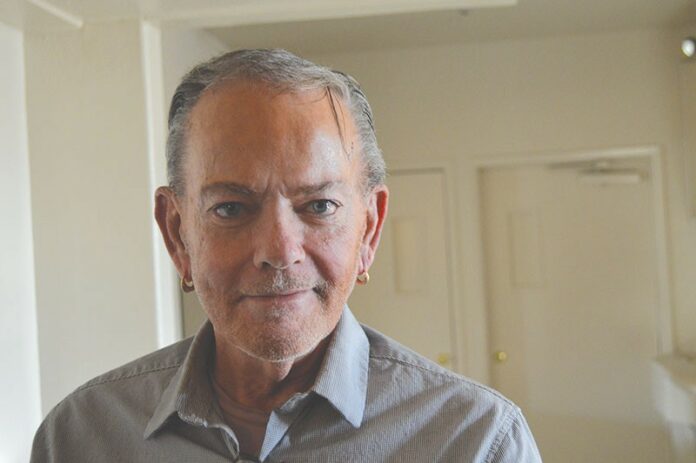

The following draft is one iteration away from my original notes. All the conversations in it come nearly or entirely verbatim from actual interviews. The novel will be called A Table for Fortune. I hope to finish it in about 2018. I thank the Bohemian for the opportunity, and my friend Greg, who was my driver and companion on the trip; the avocado stories come from him. And I thank the people of Redding.—WTV

[page]

At this time the young man named Matthew discovered a certain kind of sunshine unlike Sacramento’s, which is to say fiercer and more withering, one of time’s best weapons for degrading newsprint yellowish-orange and wrinkling people before their time; once upon a certain August which measured somewhere below far and gone in his ephemeral existence he had been hitchhiking south from Susanville and was set down in Redding where he waited five midday-girdling hours at an on-ramp whose dusty blackberry brambles were actually dripping with melted black sun-made jellies; but in the strange cool May of this current year as he hitchhiked north toward Redding the sunshine had shifted to an opposite otherness from Sacramento’s, being somehow greener in its goldenness and more wild, as if the mountains were tinting it.

The truth is that Matthew had sought sublethal sunshine in which to hide from his father, expecting most Reddingtonians to be lurking indoors in the fashion of Mohave, Calexico and Mexicali; he too would lurk, while perfecting his disappearance. On triple-digit days in Sacramento, the hardiest of the homeless trundle into thickets and culverts; those who remain sit stupefied, with heads hanging down, or else lie on the sidewalk, while flies crawl slowly over their faces. Richer souls shelter behind drawn curtains, listening to their air conditioners; and I for my part believe the city to be sustained by invisible armies of sweating, hollow-eyed air conditioner men. The sun clangs in everyone’s ears; even police veterans can get deafened . . .

So it should have been in Redding, but this wild green sunshine changed everything. And by “green” I do not mean what you might think this color should convey; it had nothing to do with the restful or menacing green glooms of Oregon. Venus flytraps and emeralds were as far away from it as palm fronds. Yes, it was green, but not exactly. It refreshed Matthew because there was nothing of him in it. No one in Redding would put a spoke in his wheel. The complementary consideration was nobody would help him, but as long as the green sunshine kept on, what could he need from this world?

In his boyhood there must have seen something that made him want to go way out into America, to find out what our country was, but whether he had been enticed by the best golden loneliness or hounded by the loneliness that lives in our homes and gnaws misunderstood children, or perhaps heard something about faraway hills in a bedtime story, whatever had provoked the wish was lost. He himself was not lost, except to his parents, who troubled over him with loving bewilderment; nor did he feel in want of anything; thus as I begin writing this I myself cannot tell you what he was going to find on what Thomas Wolfe called the last voyage, the longest, the best—in other words, the only voyage, the one toward the grave. And so, hitching a ride, Matthew left behind all the other times of his life.

As they rolled north into Colusa, with the Sutter Buttes’ dusty blue knuckles over and behind the olive orchards, the driver was saying: You know, I grew up on a citrus farm in Southern California. I picked avocados for another farmer all summer, but we used a manlift. I think avocado trees get forty to sixty feet at least. We’d have about four big bags in the cage. One flatbed truck with four bins of avocados in it, it took us all day to pick that! That gave me a real sense of accomplishment . . .

Right away, Matthew, who believed that anything he did could be undone, or done better, because it lay in his power to live any number of lives, began contemplating hiring on in an avocado orchard. First he’d grow sunburned, and then confident. Women might possibly love him.

The driver was saying: One year when prices spiked we were getting fifty cents an avocado wholesale. Wholesale! . . . —by which time Mount Shasta was glowing double-nippled against the milky clouds.

And the driver said: The boss was a real good Christian guy who’d been in the Marine Corps, and he had a mental breakdown, had to take some time off. We

were unloading avocados from

a manlift when the hydraulic

brakes failed. The thing picked

up speed, crashed into a tree. He was super-understanding when

we visited him in the mental hospital—

Just then they came into Red Bluff: red rock, long yellow grass, cool clouds. Green sunshine sped into their eyes, intoxicating their hearts. They were almost in Redding. Matthew kept grinning at the driver without knowing why. Beaming back at him, the driver said: A big tree can make more than a hundred avocados but all at different times; it takes six years to grow an avocado; I’m talking about the Hass kind, which is what I know . . .

Redding offered half a dozen exits. The driver let him off in the old downtown, not far from City Hall. —I sure appreciate it, said Matthew, and they shook hands. He lifted his backpack. Opening the passenger door, he still expected to be sunblasted in his forehead, wrists and ears, breasting an upsurge of reflected sidewalk heat which would come dryly into his lungs. But Redding was like that. He looked back at the driver, who waved, then pulled away, bound for Eugene.

There stood Matthew in Redding, wondering what to do. First he felt anxious; then he began to get excited. His plan was to have no plan. He crossed the street and began walking in the most pleasing direction, saying to himself: I do not know where I am going. I do not know where I am going. —And he exulted in this. If not even he knew this, how could anyone ever find him?

Within 10 minutes he arrived at a bar whose midafternoon quietude compelled him through the window, so he walked straight in, and the tattooed barmaid raised her beautiful face like a sunflower following light. The counter shone clean and empty. He seated himself beside the only other customer, an old hospital engineer who had just seen a bald eagle carrying a trout in its mouth. The engineer smiled at him, then said: This area is loaded with historical stuff and beautiful visual stuff. All the clouds go up and the sun goes down and you get the best sunsets.

Accordingly, Matthew decided to watch the sunset. It is true that his impressionability sometimes made him foolish. But his foolishness might have been no worse than the way that old people so often visit a new place in order to project their brilliant pasts upon its mediocre indifference. He was drawn to the engineer because neither of them were afflicted with the chronic disease called irony.

The engineer told him: It’s been a hardscrabble life. See, my dad came up here; he was a Ford mechanic; you had to love nature to come here. So this basically was the turnaround for the railroad. This was as far north as it went. You wanted to go north from here . . . Before Shasta Dam was built, you used to have to come here by boat. This is five hundred and twenty-eight feet.

Wiry and aware, he exemplified strength in age. His name was Jacob. The tendons were corded on the backs of his workman’s hands. Matthew supposed that they were becoming friends. He asked: Where would you go if you wanted to see America?

The old man said: I’ve been to Montana; I’ve built factories in the Midwest, but I’ve never been to the Deep South . . .

And right away Matthew could imagine himself in the Deep South! There he would discover what to live for. Jacob already knew how to live his life, but that knowledge must be good only for him. Matthew must find his own way; that was why he had come to Redding.

[page]

Matthew’s beer was cold and clean. When he finished it, Jacob set his down and said: I think that this election’ll be fought out on television. Here’s why there’s delegates: Here’s my good friend who has money. But I live way up in French Gulch and can’t afford to get down here. But then it gets corrupted. Like all this campaigning in this state, winner take all, and the popular vote gets set aside. But I still think we live in the greatest country on earth.

And Matthew believed. Looking right in front of him, he could see how wonderful America was! Why shouldn’t it be the greatest? And he was out in it now; he would go farther and farther . . .

Laying a cell phone on the bar, the old engineer activated its screen and showed off a photograph of his daughter, who was a smiling, freckled brunette of about twenty-five. —She’s hiked the Pacific Crest Trail, Jacob said. She loves snow camping. She’s hardcore. She and her boyfriend, they’ll go out more than thirty miles in the hills by themselves.

Matthew imagined being with Jacob’s daughter, or with any woman who would lead him into the mountains. He could not picture this angel very well; her hair altered from brown to blonde and back again. But she was holding his hand. And she knew the country—or, better yet, she didn’t, and they would explore it together. The more beer he drank, the more joyous he felt. One day he too might be happy and old, with his pockets full of eagle stories and a mountain or two in his backyard! Or else he would die in some woman’s arms.

And now the tattooed barmaid began to confide in him, saying: I told her, look, we need to get out of here. He shares custody with his ex . . . —Matthew felt lucky and grateful that she trusted him. Tenderly she set another beer before him; he had told her to pick out her favorite kind. —Once you get through altitude sickness you’ll be fine, the engineer explained. But you have to want to. You know what’s cool when you get up there? You can see the curvature of the earth. That makes you feel you’ve done something.

Matthew made up his mind to go high enough in life that he could see the earth curving down before him. He wondered if it were too late for him to become an astronaut.

Jacob was saying: We went for eleven days through the mountains. First we prepared. We buried whiskey caches, and we had fun, drinkin’ beer, cookin’ trout . . .

Matthew bought him another beer, and Jacob said: If I’d’ve known you’d be comin’, I’d’ve made a whole bunch of smoked albacore.

Will you be here tomorrow?

Sure.

I’ll come back then.

They fixed a time, and Matthew rushed out into the green sunlight to have more adventures. After the cool dimness of the bar, Redding enlarged itself all the more. He could see to the mountains. Here was Shasta County Superior Court on Yuba and West; and he stopped in the middle of the empty street, feeling as if he had found someplace where it would always be early on a summer morning. There was Placer and then Tehama; and right here stood Matthew, looking around him in hopes of learning where in America he should go.

In one of the bays behind the Greyhound station he met a bearded little man, almost elfin in profile, who had parted ways with several teeth. His face shone red and his pores were coarsened by hard living. The woman beside him looked tired and old. Their daughter was sixteen going on forty-six. They sat on the blacktop, waiting for something to happen. How this world could contain both them and Jacob was a question for moralists, sociologists and theologians, but not for Matthew, who wanted to make friends, which was why he gave the man ten dollars, and asked about his life.

The man said: Originally I’m from Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. My wife, she wanted to come back home. Now she wants to get back out of here. We came from Spokane. Everybody knows everything about everybody. Trying to rip everybody off . . . I got in trouble with the law. And then got out, found the manager of the money I had, and he never paid it, ripped me off . . .

His name was Roy. Matthew told his own name. They sat down on a bench away from the wife and daughter, and Roy began again to speak, perhaps because that strange May weather had opened the hearts of everyone, although the ten dollars could have had something to do with it. He lisped a little, on account of his missing teeth. He said: First time I been on the streets, I was seven years old. Got away from Washington, ran away to Fresno. You see, I decided to get in people’s cars and trucks and kept on goin’. Fresno was lot of killings. I started doin’ dope and went to heroin. Started doin’ it all. You name it, I done it.

Now, my wife, her dad was the head of the Hell’s Angels and I been workin’ with him since I was about seven. I made him a hundred eighty grand in about six months. And I’m one he’s afraid of. I have no problem pullin’ a gun, pullin’ the trigger and laughin’ about it. I don’t care. I got no heart.

Matthew did not care if this was true or not. He just felt happy that Roy was telling him things. And Roy said: Some guy swung on me. I walked up and popped him. When I hit him, my hands turned illegal; they’re registered. I have killed but not on purpose. I killed the head leader of the Fresno State Bulldogs. They’re Bloods and that, or I call ’em, slobs. I been a Crip since I was seven. They’re makin’ us into so many new gangs. In Portland they got the Dragon Eyeballs. A bunch of fuckin’ niggers. Oh, you’re prejudiced. No I’m not. I’m a cracker. I’m fuckin’ white trash!

And Matthew, being Matthew, could not help but wonder whether he himself might enter upon this sort of life, warring and begging and hiding, free and angry or free and scared—or had Roy paid for nothing this price of becoming bitter and maimed?

He disliked the mean things that Roy said. But since he never stopped hoping for answers and had just today in this marvelous green sunshine realized what he cared about most of all, he said: Tell me what you think about America.

Sucks, said Roy, staring into his face. —Because we keep givin’ Iraq weapons and then they’re tryin’ to bomb us. And all these people who got money and they think they been better than us.

Right away, Matthew decided that America sucked. How then could he make America better? He would start by going to the best place, and learning what made it good. So he said: I’m hiding out. Where should I go?

Fresno. People are actually really, really nice. There’s this one lady who look works out there, a Mexican lady; we call her Mama; she makes us fresh watermelon juice and won’t take no money for it . . .

Matthew thought to himself: Fresno sounds just like Redding. I think I’ll stay in Redding.

[page]

So what I wanna do, said Roy, is to be gettin’ out of here and findin’ something somehow to help us get to Fresno. I can get a one-bedroom apartment for six hundred. I was on SSI but I have a misdemeanor warrant. I got caught with thirteen days in the county jail. I have a problem with authority; I’m unextraditable.

And then what?

I wanna own some more land and be happy.

Should I do that, too?

Why fuckin’ not?

Up until now Matthew had supposed that his life would somehow make something, not a child but something else. It might be that he would improve the world, or even save it—but never bit by bit, as if he were some nine-to-fiver ageing for the sake of a paycheck from which he would save nothing but money. But maybe land, a woman and a child would be his destiny.

Trustingly he asked Ray: What’s the most beautiful kind of woman’

Smart. Looks, I don’t care about looks. I mean, I dated girls this big. I dated girls that big. This one here, I did fifteen years in the slammer and she never left. She never wrote me but she was there when I got out. Plus, I got eight kids, and she don’t mind.

That’s good, said Matthew. Where can I find a woman?

Roy called over to his wife: Baby, where’s a good place to buy a bitch?

Off of Cypress, by the park.

When does what’s-her-name the black bitch show up there?

About nine-thirty, ten o’clock.

Roy remarked evenly, with triumphant contempt: I know every Spokane ho in there. In Pullman I know ’em all cause they’re all mine. There was one nigger and I took every one of his prostitutes except one, and I didn’t take her because she’s fucking ugly.

Thanking him for his advice, Matthew walked on. Should he make a child, wander the Deep South or pick avocados? His eyes were on the bright green sunlight of Redding. Had he told anybody, your sunlight is green!, it might not have turned out especially well for Matthew, so he kept quiet as always, studying the people and trying to decide whether he should become one of them.

Against the outer wall of the Amtrak station lay a homeless man who explained: This place is my living room. —Gesturing at the tracks and the Greyhound station behind them, he said: There’s my TV.

Matthew leaned up against the wall beside him. He asked: Do you have a good life?

The man said: I’m from Alturas. That’s a really small town. If you’re on the main street after ten o’clock at night the police are gonna take you in. Here, nobody bothers me because I keep it clean. I pick up after myself and others. And I’ve learned how to be happy. I’m happier here every day. I want to stay right here, all my life.

Matthew thanked him. He decided he believed him. Perhaps the man was Christ, or one of His relatives, in which case what Matthew should do was sit down right here and watch the tracks for half a century. But for some reason he found himself continuing on.

He walked up and down, then closed his eyes, pretending that something better or worse than Redding would appear when he opened them; that was a game he had often played, and until today the results had been consistently disappointing; just now he opened his eyes and was glad to still see Redding.

Now he had better find a room. Twenty minutes later he was watching the paling of the cloudy sky from the second floor deck of the Sunshine Motel where somebody in Room 29 was plinking on a ukulele and singing in imitation of Neil Young while a cool breeze came from the cottonwoods and the cars in the parking lot did nothing but sparkle. It was all new to Matthew.

He looked around his room and loved it. No one would find him here. He had paid the Gujarati desk clerk thirty-two dollars cash, no identification required. He lay down on the big double bed and decided to get a girlfriend and bring her straight here. He still wanted to make a child.

Locking his door, he descended to the street, found a restaurant and ordered a hamburger. The waitress was sweet; he felt happy just gazing shyly at her hands; so he asked whether she would like a drink. He never expected her to say yes, but she did, because this was Redding, where everyone was friendly, at least while the green sunshine lasted. He was drinking beer; she poured herself a shot of vodka and thanked him. Then she went to attend to her other customers while he returned to his hamburger—the best ever, of course.

Ten minutes later she was back at his table, so he bought her another drink. She told him about her marriage, her child and her vacation; he bought her shots and she kept giggling and saying: What are you trying to do to me?

Make you happy, he said. —And in truth that was all he wanted.

Then she brought her friend the barmaid who she said was amazing, and the two women stood drinking together sweetly, flirting with him, after which they offered him a free dessert. Matthew thanked them and said he was too full.

The waitress leaned her hip against his table, smiling, and now he could see the bright green sunlight rising up from her; she might have been the one he was meant for.

When he went up to pay, the barmaid took his hand. This too was ever so sweet. He almost felt as if she would have gone with him, which unnerved as much as flattered him. Which one should he make a child with? Feeling happy and embarrassed, he quickly walked away. As soon as he had rounded the corner he began to feel ashamed; he had probably disappointed the barmaid. But what if she had only meant to be kind to him? He did not go back.

It was dark now. He returned to the motel, then went into his room feeling happy. He thought about the homeless man whose television was the railroad tracks and everything beyond them. He might be the most fulfilled person on earth. Why shouldn’t Matthew do the same? Opening the door, he took out a chair and sat awhile looking out across the world. The lovely shadows of the railing kept curving around on the bright deck and a man ran across the parking lot, while the smell of stale food rose up in the cool breeze, mosquitoes biting Matthew silently, and across the parking lot the jumbled white squares of the letters MOTEL supported a great yellow sun with orange neon rays shining out from it.

He realized that he had failed to watch the sunset. The old engineer in the bar had told him about Redding sunsets, and he had forgotten. Well, he would do that tomorrow night.

At ten o’clock, Virginia, who was sixty-three but looked a hard, sexy forty-three, came knocking at the door of the adjacent room because some girl had stolen the vacuum cleaner; he promised that it wasn’t him and that he lacked any connection to that unknown girl. Virginia believed him. He asked her how the motel was, and she said: Oh, they’ve cleaned it up real good. We’re not even on the bad list no more.

She had been living in Room One for two years. Her son lived there also. He asked what she thought about America, and she said: What’s not to love? —Right away he realized that she was right; how could he not love his own country? He wanted everybody to be right. He would feel better believing in everything.

Virginia rushed off and he could see her sweeping the sidewalk down by the office. She wanted the place to look good for the Greyhound drivers who checked in at night and slept during the daytime.

Matthew wandered in and out of his room. It was ten-thirty; Virginia kept sweeping the sidewalk. Two doors down, the magnificent black woman who had been haunting the doorway upstairs now stood patiently facing the parking lot, half-smiling, with her arms folded across her big breasts.

Reminded by her of the prostitute who according to Roy’s wife would now be working “off of Cypress by the park,” he considered hunting for her, but decided that he liked Virginia better. Maybe when she had finished sweeping he would ask her if she wanted to travel the Deep South with him and buy land.

And Matthew stood listening to the world. To him it was all very wonderful.