Shortly before he died on Nov. 22, 1916, Jack London told his second wife, Charmian, “I will be smiling at death, I promise you.” Eight years earlier, in Martin Eden, his autobiographical novel, he wrote of his protagonist, “Death did not hurt. It was life, the pangs of life . . . it was the last blow life could deal him.”

Ever since London’s death in Glen Ellen 100 years ago, biographers have tried to explain why and how he died. Earle Labor, the author of Jack London: An American Life, the most recent biography, published in 2013, argues that he died a natural death. Others have insisted that London took his own life either accidentally or on purpose with an overdose of morphine. Clarice Stasz, a former Sonoma State University professor and the author of 1988’s American Dreamers: Charmian and Jack London, observes that, on the subject of suicide, “the verdict will always be out,” though she adds that it is “unlikely.”

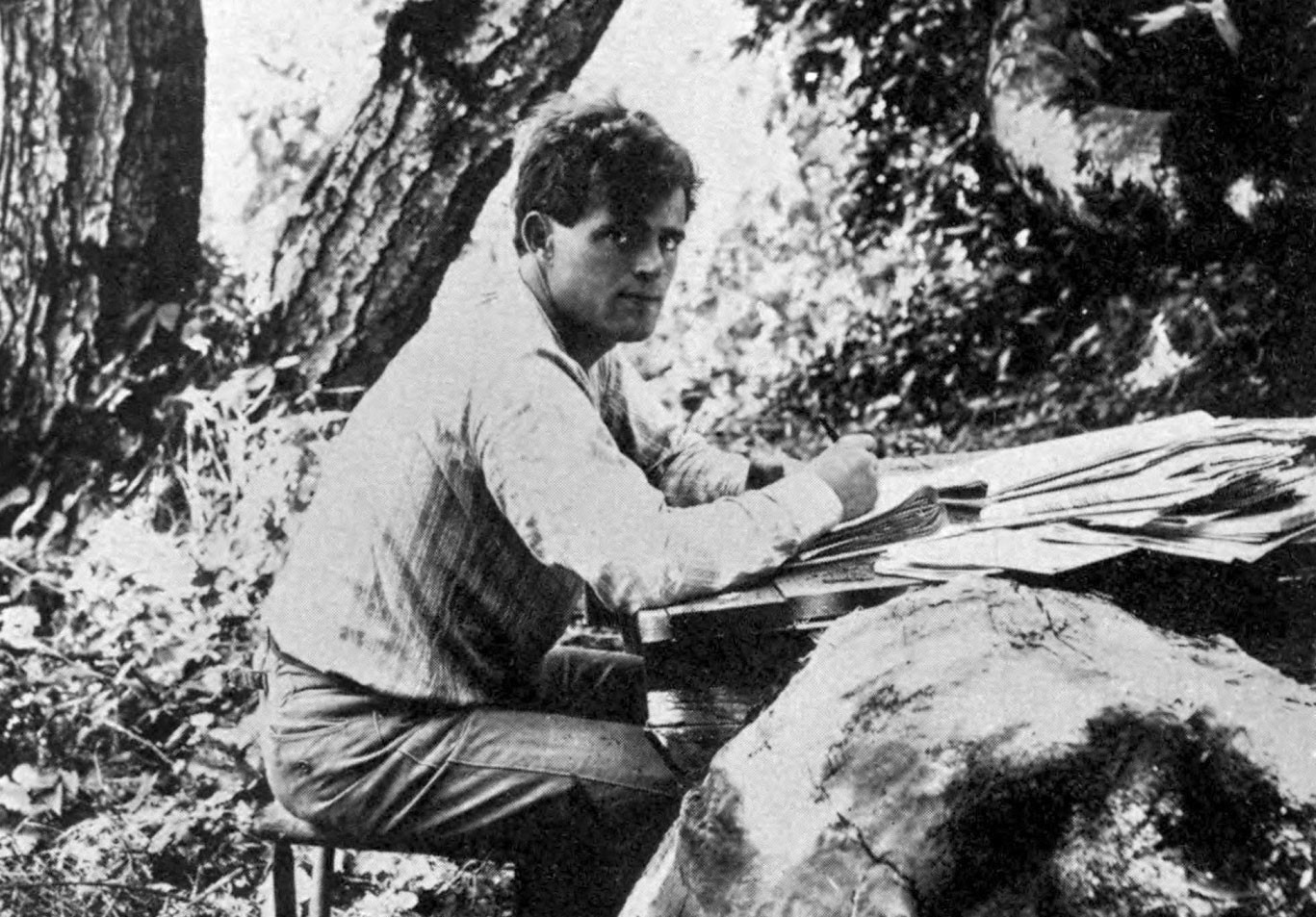

On the anniversary of London’s death at the age of 40, scholars and fans all over the Bay Area are honoring the life and the work of the San Francisco–born, bestselling writer who fought for animal rights, farmed organically at Beauty Ranch, called for the prohibition of alcohol and hoped one day to see a socialist America.

Twice he ran for mayor of Oakland and lost. From about 1895 to 1916, he traveled almost nonstop, first as a hobo who rode the rails and then as a famous globetrotter, and, when he wasn’t farming and ranching in Glen Ellen in Sonoma County, he was surfing in Hawaii and popularizing the sport.

No California author lived more fully and more vigorously than London—no one loved life more than he—and probably no author hastened his own death more than he, not even F. Scott Fitzgerald, who lived four years longer than London.

In her two-volume biography of her husband, The Book of Jack London published in 1921, Charmian noted that he suffered from terrible headaches, insomnia, psoriasis, dysentery, pyorrhea, rheumatism, scurvy, and that with his diet “was nothing less than suicidal.”

A workaholic who often wrote a thousand words a day, day after day, he was one of the first celebrities to describe, in 1913, his own substance abuse in John Barleycorn, his “Alcoholic Memoirs,” about which he wrote “the only trouble, I must say . . . is that I did not put in the whole truth. . . . I did not dare put in the whole truth.”

What didn’t he dare say? That his biological parents weren’t married when they lived together in San Francisco in the 1870s, and that his mother, Flora Wellman, a spiritualist, put a gun to her head, pulled the trigger and wounded herself before she was taken, in “a half-insane condition,” to a doctor on Mission Street. That’s what the San Francisco Chronicle reported on June 4, 1875. Flora’s common-law husband, William Henry Chaney, abandoned her during her pregnancy and denied his son’s paternity when London wrote to ask about his origins before setting out for the Klondike to prospect for gold and to find himself.

Georgia Loring Bamford, the author of The Mystery of Jack London—one of the very first biographies of the author, published in 1931—understood implicitly his enigmatic, elusive identity that made it impossible to pin him down, or pigeonhole his work.

London wrote science fiction, tales of adventure and horror, travel narratives, a dystopian novel titled The Iron Heel that tells a riveting tale of oligarchy and revolution, a subject he discussed during a lecture tour that took him from the campus of UC Berkeley to Harvard and Yale, where he urged Ivy Leaguers to take to the streets and protest injustice and inequality.

Readers who don’t know anything about London might visit Jack London Square in Oakland or admire the plaque at Third Street and Brannan that marks his birthplace on Jan. 12, 1876. Those who want to know more can go to Jack London State Historic Park in Glen Ellen and view the ruins of Wolf House, his and Charmian’s dream house that was destroyed by fire in 1913, a tragedy that hastened his final decline.

Moreover, every Bay Area library and bookstore has Jack London’s books galore, though perhaps not all 50. One can start anywhere and jump around

from The Call of the Wild to

The Cruise of the Dazzler, Martin Eden, The Road, The People of

the Abyss, The Scarlet Plague and The Star Rover, a bibliography that combines fantasy and time travel with an expose of prison conditions at San Quentin. Each book is different and each carries the unmistakable stamp of originality that belongs to the literary genius born John Griffith Chaney and whom the world knows as Jack London.