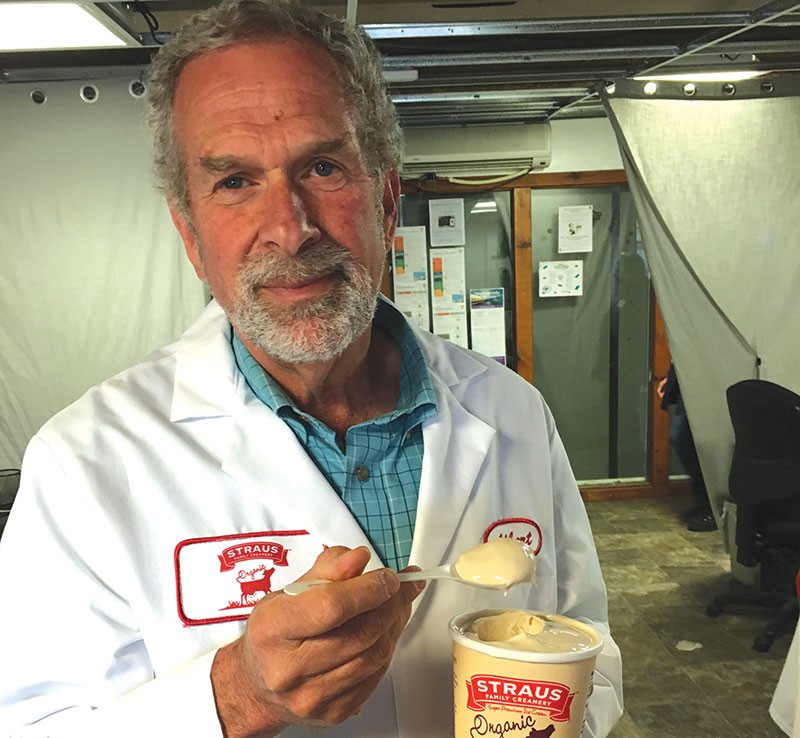

‘We’re not for sale,” says Albert Straus, as pints of soft, mushy coffee ice cream come down the conveyor belt at Petaluma’s Straus Family Creamery and are placed in a freezer at –20 degrees so they’ll harden almost instantly.

“When companies go public, they often care less about values and more about the return on the investment.”

The creamery’s founder dips a spoon into one of the containers, before it’s sealed, and tastes it. In comparison to national brands that are available from coast to coast, Straus ice cream is sold largely in the Bay Area, and, as a privately held company, is not traded on the New York Stock Exchange.

“These are volatile times in the milk industry,” Straus says. “On the one hand, there’s overproduction of milk globally, which has decreased income for dairy farmers. On the other hand, consumers are demanding higher milk-fat products, which has created a shortage of cream and milk fat.”

Dairy farmers from Holland to Ireland and California are facing uncertain futures. Marin once boasted hundreds of dairies that stretched from Marshall to Novato and Petaluma. Today, there are less than 25 in the county.

So what does Straus Family Creamery do? Make more ice cream, in more flavors than ever before, and hope to save rural communities in the process.

Straus ice cream—which comes in 11 different flavors—is made in small batches and with minimal processing. The first flavors introduced were chocolate, vanilla and raspberry. Now they include raspberry chocolate chip, Dutch chocolate, strawberry and lemon gingersnap. Straus soft serve, which has seen a 20 percent growth in sales in the past year, is available at a half-dozen outlets in Marin County, like Pizzeria Picco in Larkspur and Cibo in Sausalito.

The ingredients in Straus ice cream are milk, cream, sugar and eggs (as a stabilizer). No gums, thickeners, stabilizers, artificial ingredients or coloring agents are used. Straus cows graze on pesticide-free pastures in both Sonoma and Marin counties.

In Marin, dairy provides more revenue than any other single aspect of agriculture. In 2016, dairies brought in $43 million.

In Sonoma, the figure was

$147 million. Neither grapes nor cannabis are big money makers for Marin farmers, though they are in Sonoma County.

This year marks the 15th anniversary of Straus Family Creamery ice cream. Next year is the 25th anniversary of the creamery itself, which Straus founded in 1994. Today, he’s the CEO, and face and voice, of the company. His father, who was a refugee from Hitler’s Germany, started Straus Family Dairy Farm in 1941. Albert Straus transformed the farm into the first certified organic, non-GMO dairy west of the Mississippi River.

“We’re about the triple bottom line,” Straus says. “If you’re not supporting working families and you’re not protecting the environment, you’re not a sustainable business no matter how financially successful you are.”

At a time when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is loosening labeling rules, Straus has stayed true to his original mission to keep GMOs out of the company’s ice cream, milk, yogurt and sour cream. More than a year ago, the food industry—hard on the heels of Trump’s anti-regulation agenda—sought to end Obama-era rules governing the disclosure of calories, sugar, fiber and serving size.

The pace of deregulation has accelerated, though all Straus ice cream containers continue to provide a list of nutritional facts, including calories, cholesterol, carbs, sugars and protein.

Transparency has helped Straus sell its ice cream. So has hot weather. The company sells 50 percent more ice cream in the summer than during the rest of the year. Straus wouldn’t reveal annual sales figures, but the North Bay Business Journal last year estimated the figure between

$30 million and $40 million.

By riding the consumer desire for organic, non-GMO food, Straus has found a niche in the crowded, competitive market dominated by giant corporations like Breyers that make ice cream with corn syrup, powdered milk and whey.

Straus has collaborative relationships with eight other family farms in the North Bay. All boast the red and white Straus sign, which features a happy cow with a large udder. By cooperating, they’re able to survive and thrive in the crazy milk market.

Straus is phasing out Holsteins in favor of Jerseys, because Jerseys produce milk with a higher fat content. In his 2018 book, Milk! A 10,000-Year Food Fracas, Mark Kurlansky explains that milk with a high percentage of fat has long been considered healthier than low-fat and skimmed milk.

The fat content of Jersey milk is 4.9 percent. The milk fat content of the Holstein, the most common U.S. dairy cow, is 3.7 percent fat, with a 3.2 percent protein level. Protein content for Jerseys is

3.8 percent.

Straus says that he came by his social conscience and his environmental awareness gradually. His mother, Ellen, along with Phyllis Faber, founded the Marin Agricultural Land Trust and later the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin that has inspired at least two generations of ecologically minded citizens.

In high school, Albert started s recycling club. At Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo, he majored in dairy science, took a class on ice cream making and served on a dairy-judging team.

“I always had the intention of making ice cream,” he says. But other projects took precedence. Ice cream production started small. It took years to develop an organic strawberry ice cream that Straus liked well enough to put on the market. Indeed, not everything has gone smoothly.

“In 1995, a Japanese company wanted us to export our ice cream,” Straus says, “but that fell through.”

In the next two to three years, Straus plans to build a larger, more technologically advanced creamery closer to major markets—somewhere not yet determined along the 101 corridor.

Relocating will mean more commuting time for Straus, but it will help many of the 85 employees at the creamery who drive long distances to get to Petaluma.

Straus also dreams about revitalizing the kinds of rural communities that were once the lifeblood of the North Bay but which have slowly withered.

“For us,” Straus says, “money is secondary to the quality of life for our family, for the surrounding community and for our employees.”

Jonah Raskin is the author of ‘Field Days: A Year of Farming, Eating and Drinking Wine in California’ and an occasional contributor to the ‘Bohemian.’