Motor Dudes

Michael Amsler

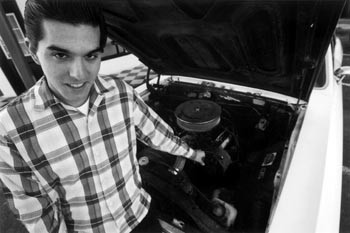

Making Lemonade: Derek Irving, guitarist for local faves the Aces, sometimes feels that all he does is to throw money into his car, only to hear it emit a metallic belch and demand more. Undaunted, Irving is saving up to have his ’67 Chevelle Malibu painted.

Classic cars for cool cats–on the cheap

By Christian Chensvold

SO YOU’RE YOUNG and cool and shopping for a set of wheels and it’s gotta be hip cuz you’re not about to cruise through life on the Highway of Anonymity in a Honda Accord. Your tastes are notably esoteric and a tad vintage, and you know that nothing causes uncontrollable drooling quite like a classic car. But since you’re still paying off your student loan, you’re not about to splurge on a 1932 Aston-Martin. Actually, by “classic” you simply mean something older than you are.

Say you’ve got five thousand bucks. Can you do it?

At age 17, Ryan Powers did. His cherry 1960 Chevy Impala is red and white with chrome shiny enough to mirror the grease in your hair, sports whitewall tires (the automotive equivalent of a top hat), and truly deserves the fuzzy dice that dangle from the rear-view mirror.

This is his first car. His parents bought him the Impala, which makes him sound even more spoiled. In fact, the car was had for a mere $3,500 from a co-worker, and had only 40,000 miles on it. Except for a slight quirk when shifting into second gear, this older car runs splendidly.

With its good ole American confidence and charm, Power’s impeccable Impala puts him way ahead of his high school peers in the coolness department. The rich kids are driving their shiny-new practical and efficient Japanese imports while everyone else drives whatever he or she can. Powers admits to being slightly spoiled, and knows there’ll be no settling for a Honda after a car like this.

Powers was drawn to the car’s classic cut after tooling around for several years in his older brother Brennan’s 1965 Chevy Impala, a burly, masculine car that mom and pop bought him five years ago for $4,500. “It’s big and it’s old,” Brennan says fondly. “And I’ve grown to appreciate the simplicity of it: no computers or anything.”

Brennan performs much of the maintenance himself, he says, because older cars are easy to work on. He took an auto-shop class and can now resurface the car’s brake drums, plus perform a host of other technical tinkerings that most of us wouldn’t dare attempt for fear of endangering our lives.

The car had only 800 miles on a new engine when he got it five years ago, and 83,000 miles on the rest of it. “All my friends say I’m lucky to have it,” Brennan says, “and I am.” Both he and Ryan are constantly asked for rides, and whether they’re selling.

They’re not.

Depreciation Appreciation

It is one of those terribly misguided myths that classic cars are expensive to own and insure, says John Mohar, owner of Petaluma’s Showcase of Motorcars. In fact, he says, classic cars are an all-around better value, and people are finally catching on to this. In the past two years Mohar’s average customer profile has grown gradually younger, and now a full half are buying the old cars as their primary form of transportation.

This change has been sparked by an extreme increase in the price of new cars, combined with rapid depreciation, says Mohar. Classic cars keep their value and can even go up, while new cars will only go down, including their initial depressing plunge of 30 percent the moment they’re driven off the dealer’s lot.

Besides the moral uplift from recycling old steel and practicing historic preservation, maintenance is cheaper on old cars, with most of them tuning up for only about $100, in contrast to $400 for a new car. “The new ones are so complicated and so computerized,” says Mohar, “that [mechanics] have to spend more time,” racking up their bill in the process. And while insuring a new car, because of its greater expense, generally runs $1,000-$2,000 per year, the average classic car costs about $400. “Insurance companies realize that the people who buy these cars take better care of them–they protect and watch them,” he says.

Mohar stocks about 100 cars at a time, a third of which have been restored, often in mint condition. They frequently have new engines with only a few thousand miles on them. Surprisingly, most of his to-die-for cars are priced in the $10,000-$15,000 range. What’s more, Mohar offers financing at competitive rates. He sells an average of 17 cars per month, and confesses to owning “a lot” of cars himself.

Is there a greater risk for theft with classic cars? Probably not, since the most stolen make of car is the Honda. Arguably, the more exotic a car is, the less likely a criminal would be to try to drive it away since it would be so easy to spot (then again, thieves are not known for their great mental perspicacity). Most cars are stolen for parts, since a thief can get three times the car’s value by peddling it piecemeal.

Lastly, there is the prestige factor of having a car that’s poetic and not prosaic, cool and not common. “They’re special interest, limited production, and disappearing all the time,” says Mohar. His most popular make and model is the Ford Mustang convertible, which seems to be Middle America’s idea of the ultimate set of wheels in which to escape from itself.

Mohar admits that most of his customers are motivated more by nostalgia than the perception that classic cars are a better value. For baby boomers, Mustangs, Corvette Stingrays, and ’57 Chevys rekindle fond memories of those pre-sexual revolution days of drive-ins, sock hops, and necking sessions at Inspiration Point.

“The newer cars don’t have anything to relate to,” says Mohar.

Michael Amsler

While the French have managed to make their mark in everything from philosophy to cheese, automobiles have never been their forte. Yet there are no fewer than trois Citroëns in Brisebois’ extended family.

Thunder Road

Lou Greene is a car-reanimator, a kind of shaman-mechanic who brings Ford Thunderbirds back from the dead. In his hands, some 20 cars have risen from their ashes like rusty phoenixes, and in 1991 one of these won Best of Show in a national classic-car competition. That’s best of show in the entire country. And then he got rid of it.

Greene is a member of the Thunderbirds of Sonoma County, one of over two dozen car clubs in the North Bay that offer the chance to schmooze and gab about one’s favorite make and model. Group members gather monthly to show off their Fords made between 1955 and 1957.

Greene, an appliance repairman by profession, buys dilapidated T-Birds for $9,000-$18,000, spends up to a year restoring them, and then, like an artist severing the umbilical cord of creation, sells them, garnering $16,000-$42,000. With the high cost of restoration, Greene says he hardly makes a profit: this is simply his idea of fun.

Huh? “You could call it midlife crisis,” he grins. “It gives me something to do.”

A rather informal, blue-collar group, the Thunderbirds of Sonoma County, like other car clubs, nevertheless practice a kind of cliquish tribalism. Car connoisseurs are interested in meeting with their own kind, and the club becomes a support group for mysterious knocks and pings. You can almost picture them telephoning each other in the middle of the night and gasping, “It’s my carburetor! What should I do?”

Ford Thunderbirds belong on that list of sacred Americana that includes mom and apple pie. The two-door “small birds,” as they are affectionately called, were in production for only three years, during which time some 60,000 were manufactured. Today they can be had, restored, for about $20,000.

The Thunderbirds of Sonoma County boast 40 members and 25 cars. Their monthly meetings usually involve a caravan around the county, and the group often shows its cars at various cultural activities. Most members use the cars as recreational vehicles on the weekends, but a few use the T-Birds as their everyday vehicle.

Members describe the pride of ownership as a “big ego trip,” and how could it not be? Some have a license plate designating the car a historical vehicle. Besides making the driver look important, the license plate, which is available from the DMV for any car 20 years or older, lowers registration costs when the car changes hands.

Club president James Arieta bought his T-Bird out of a newspaper ad for $15,000 five years ago, and has since put another $10,000 into it. Members have been known to splurge $5,000 on paint jobs. Insurance is still very reasonable for these show-quality cars. Arieta pays a miniscule $225 per year for full coverage, though his car is listed as a recreation-only car.

Sisyphus and the Citroën

“It’s not quite a cartoon car,” says Ray Brisebois of his ’56 Citroën, “but it’s warm and fuzzy and people like it and kind of want to hug you for it.”

Brisebois owns a car that is actually less classic than it appears. “When you look at it from the front, it looks like a ’34 Ford,” he says. “So it’s like living in the ’30s with ’50s production.” Indeed, the auto is stately in a rather exaggerated way: The headlights stick out like miniature street lamps, and the back seat is roomy enough for an amorous couple to perform half the positions in the Kama Sutra.

And while the French have managed to make their mark in everything from philosophy to cheese, automobiles have never been their forte. Yet there are no fewer than trois Citroëns in Brisebois’ extended family. He bought his for $7,000 in 1990 and has since been on the road to restoring it–an arduous path that is as long and winding as the road to salvation.

Brisebois, who owns a small picture-frame manufacturing business, has done no work on the car himself. He has put another $7,000 into it, part of which is due to his own poor luck in choosing mechanics. “There are people who want to take your money,” he offers as a caveat. “They think this is spare income, so they’re merciless.” However, he does admit that the car has only 1,000 miles on its new engine and runs just swell.

One of the Citroën’s curiosities is its three gears. Then there’s the air-conditioning system, which consists of turning a knob to open the front windshield, and the wipers, which have a manual overdrive allowing you to wipe away a few drops of precipitation by hand-cranking the wiper knob.

Like Richard Wagner, the composer who took 25 years to polish up Der Ring des Nibelungen, Brisebois has been restoring his car for over seven years and still isn’t finished. This is not only frustrating, but pangs at the very heart of ownership: “Until you get everything redone,” he says, pausing emphatically, “you don’t have the feeling that it’s yours.”

Brisebois also owns, in contrast to the Citroën, another oldie, a 1970 Jaguar XKE that he bought for $11,000 and has successfully restored. “It’s lean and sleek and a very sexy car,” he says of the silver, retro-space-age set of wheels.

But, of course, he’s put enough money into the Jaguar to buy a small mansion in the Midwest. “That’s what happens when you start at one end and finish at the other,” he says, punctuating his words with a faintly audible moan.

Beautiful Suffering

Being cool has its price. The French have a saying for this (the French have a saying for everything): Il faut souffrir pour être belle–”One must suffer to be beautiful.”

After all, when you buy a lemon there’s nothing to do but make lemonade. Derek Irving isn’t completely soured, but at times he feels a bit like Tom Hanks in The Money Pit, throwing money into his car, only to hear it emit a metallic belch and demand more.

Four years ago Irving, a shipping clerk and the guitarist for local blues boys the Aces, bought a white ’67 Chevelle Malibu with 170,000 miles on it for $3,500 through a newspaper ad. Irving enjoyed a brief honeymoon with his new wheels–big and burly and faintly suggesting a racing stock car–until the engine went kablooey. Seems there was that little matter of changing the oil. “I always check it now,” he assures. A new engine carried a price tag of $2,200. Then, practically moments later, the transmission went. Replacing that cost $1,100, leading Irving to ruminate, “Am I restoring this or just keeping it running?

“Unfortunately with older cars,” he adds, “unless you can work on them yourself or have a lot of money, they’re a problem.”

Fate can be cruel. Irving once had a ’57 Chevy but found it so expensive to maintain that he sold it. Now he’s thrown so much into the Malibu he says he might as well have kept the Chevy.

Irving’s next aspiration is to get the car painted. But given the cost, “that might take five to 10 years,” he sighs. “I’m serious. Every time I have some money there’s a new noise to get checked out.”

Looking cool makes up a little for all the trials and transmission tribulations, Irving says. At stop signs he is frequently flashed the thumbs-up seal of approval. “But if they only knew!” he laughs.

In the four years since buying the Malibu, Irving has learned a lot; more about life than cars. He admits his knowledge of his automobile is rather limited: He knows how to fill it up. Which, incidentally, runs about $25.

Boy Toys

The reader would have to be asleep at the wheel to fail to notice that car enthusiasts are virtually all men. For the male of the species, says Santa Rosa psychologist Bruce Denner, the car is “invested with a power and meaning way beyond its utility. It’s a symbol of freedom, especially sexual freedom.

“Men have always resisted socialization into family, home, and job,” Denner adds, saying that the car offers freedom from domestication with its overtones of emasculation.

For the middle-aged classic-car buff, the restored (read: rejuvenated) car comes to represent his vanished youth. And for the young male, the first car brings to him freedom of mobility combined with a lack of parental supervision. Women seem to respond accordingly. Stag films from the roaring ’20s, that heyday of the newly liberated and hot-to-foxtrot flapper, often made use of the car as the ultimate, well, vehicle for sexual abandon.

Says Denner, “The ’20s were a great period of sexual freedom for women, and they were willing to do things in the car that they weren’t willing to do in the parlor.”

Indeed, owning a car has always boosted the young male’s chances of getting lucky. And owning a cool car would seem to boost them even more.

But who is it really that men are trying to impress with their cool cars?

Legend has it that the fairer sex is swayed by peacock-y displays of wealth, bravura, and style–those things that symbolize power, confidence, and virility. But a deeper investigation into the nature of masculine competitiveness reveals that the cool car is something a man takes pride in not because it impresses women, but because it impresses men.

And no car is cooler than the classic car. Its retro-hip style shows that its driver is one step ahead of–or behind–the others, and it confers upon him a dashing quality symbolizing sexual readiness. Big, powerful, and ready to conquer, the classic car is an expression of lust. And its destination?

The garage.

From the December 31, 1997-January 7, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.