Up for Review

Happier Times: Ayling Wu, first-born daughter Karolyn (now 5), and Kuan Kao.

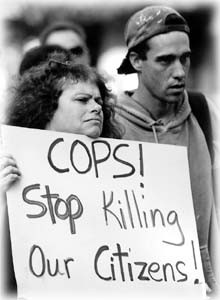

Law enforcement balks, but social justice advocates say recent spate of police shootings shows need for civilian police review boards

By ****@*****ro.com“>Greg Cahill and Paula Harris

IT TOOK 30 SECONDS and a single bullet fired by a veteran Rohnert Park police officer to shatter the lives of Ayling Wu and her three young children. Sirens wailing, two police cars screeched to a halt at 2:30 a.m. on April 29 in front of the manicured lawn of Wu’s house on a usually quiet Rohnert Park street after a dozen 911 callers reported her husband, Kuan Kao, standing outside, yelling, and brandishing a 6-foot pole “martial arts style.”

Police Officer Jack Shields ordered the 33-year-old Kao–a computer quality assurance manager who earlier that night reportedly had spent several hours at the Cotati Yacht Club, drinking two bottles of red wine and scuffling with a pair of bar patrons over racial slurs–to drop the pole. Instead, Kao swore at Shields and slammed the pole against the hood of the patrol car. Wu tried to intervene, telling Kao to give her the stick. The officers yelled for her to back off. Wu turned, trusting the officers to disarm her husband. A second later she heard the gun shot and saw Kao fall to the ground several feet away, his chest heaving for breath.

A registered nurse, Wu tried to run to his side to administer CPR. Police restrained her. By the time paramedics arrived 10 minutes later, Kao lay dead in handcuffs.

“I just had to watch him die,” Wu recalls sadly.

In a written statement, Rohnert Park police officials called the shooting justified, saying Shields feared for his life because Kao was waving the stick “in a threatening martial arts fashion.” Wu insists that Kao had no martial arts training.

“The whole police department needs to look inside their administration really carefully before they give anyone a gun,” Wu says.

Sonoma County District Attorney Mike Mullins is reviewing a Sheriff’s Department probe into the shooting. The FBI, at the behest of U.S. Attorney Michael Yamaguchi, also is investigating the case.

But the shooting–one of eight cases in which suspects have died or suffered severe injuries during confrontations with local law enforcement officers in the past two years–has sparked several angry protests over the alleged use of excessive force and prompted charges of possible racism.

“We really want justice,” says Nancy Wang, president of the Redwood Empire Chinese Association. “I appreciate that police protect us, but they have a lot of resources for dealing with these kinds of situations. . . . Kao was disturbing the peace, but he had no hostages and didn’t deserve to die.

“Amazing, 30 seconds–where were Mr. Kao’s human rights?”

More on Citizen Review Boards.

Police Resistance

IN RECENT WEEKS, Kao’s death has fueled a move to create civilian police review boards to scrutinize the actions of local law enforcement agencies.

“It seems like there are more instances [of police brutality],” says Jeff Ott of the Santa Rosabased Copwatch. “Now is the right time [for independent review of police actions].”

Local members of the American Civil Liberties Union already are laying the groundwork for civilian police review boards. “In my opinion, 90 percent of police officers are doing an excellent job–they’re laying their life on the line for you,” says Rene Lopez of the Rohnert Parkbased National Latino Police Officers Association. “But there are a few that we need to control, because those people have got the authority to draw a weapon and kill you.

“We need somebody to oversee them because the police departments are not going to go out and conduct an investigation to find themselves guilty. We need someone else to look into matters.”

Lopez, an ex-state Department of Motor Vehicles investigator and Novato resident, heads the civilian police review board in his hometown, the only such organization in the North Bay. He also is chairman of a local ACLU subcommittee studying the issue.

“If you run a solid police department and do everything by the numbers, why would you object to a police review board?” he asks. “You should be glad to have a police review board take a look at what your department is doing. But if you’re always trying to hide things and something goes awry, then you don’t want people to look at it.”

But the concept is running into stiff resistance locally. Acting Sheriff Jim Piccinini points out that there already are several ways to review police conduct, including internal departmental review and investigations by the District Attorney’s Office, the Sonoma County grand jury, and the state Attorney General’s Office.

“You have to decide if there are sufficient review procedures in place,” Piccinini adds, “or if one more would slow the process.”

Bucking the Trend

THROUGHOUT the United States, there has been a sharp rise in the number of citizen review boards in the last five to 10 years, according to John Crew, director of the Police Practices Project for the ACLU of Northern California. “Of the 50 largest U.S. cities, more than three quarters now have some form of civilian review board. University of Nebraska Professor Sam Walker has documented an enormous growth in suburban- and medium-sized communities creating civilian review boards,” Crew says.

“That growth is occurring at the same time there’s a nationwide trend toward community policing,” he adds. “The police want to work in partnership with the community, but it makes no sense to extend their hand in partnership and then withdraw their hand to take part in an internal affairs system where they police themselves in secret.”

The increasing concern about financial claims filed against police departments and a desire to make sure that cities are not wasting tax dollars on expensive public safety programs is another reason for the growth of civilian review boards.

Additionally, civilian review of law enforcement agencies is better understood now than it was in the ’70s, Crew explains, when it was seen as an anti-cop thing. “Now it’s more about good government than bad cops. Police have unique powers, can directly deprive someone of their freedom, can arrest them, can use excessive force, can even use deadly force. We need some independent method of checks and balances. Even San Diego County–a very conservative area–has recognized this.”

Indeed, the concept has matured and been professional in recent years, he adds, so that it’s become difficult for law enforcement agencies to claim that civilian review is a boogeyman that’s going to destroy law enforcement.

“Sonoma County is a holdout and bucking the trend,” Crew concludes. “Sure, the FBI will investigate the death of Kao. But the FBI operates totally differently than a civilian review board. The FBI will have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the officer is guilty of a crime. That’s really hard to do. The FBI won’t look at issues such as: How did the officer get himself into that position? What mistakes may have been made? Did the officer comply with policy? Should the policy be changed?”

Closed Society

“AS A YOUNG POLICE OFFICER, I had a problem with any kind of interference in the police department,” says John Parker, an ex-Oakland police officer who now heads the San Diego County Citizen’s Law Enforcement Review Board. “My opinion changed as I became more sensitive to what the community needs–more accountability. I saw damage being done by the code of silence employed by many police officers, and I couldn’t abide by it.

“It made me an outcast, just as much as someone who had complained about the police from the outside.”

In San Diego County, the civilian police review board won overwhelming public support as a ballot measure in 1991; the city of San Diego had a review process for several years. Yet, local sheriff’s deputies are still fighting against being brought before the board and having to testify, Parker says.

“Law enforcement is a closed society, they want to police themselves,” he observes. “They want to believe that no one understands policing other than trained law enforcement professionals, but any intelligent adult can read and comprehend written police procedures and rules and regulations, and know or learn what officers are supposed to do in given situations.”

The bottom line, he adds, is that police officers are public employees who work for the citizens, and those citizens have a right to ensure that the police are accountable.

Secrecy and deception are built into the policing system, Rene Lopez says. “If you are a line officer and something goes wrong, you’re not going to snitch yourself out to your superiors,” he points out. “Is the sergeant going to snitch himself out? Is the lieutenant going to say, I knew the sergeant and the line officer were screwing up under my supervision? Hell, no! So the top guy often doesn’t know what’s going on in the ranks because nobody tells him anything. People just aren’t going to come forward to say, I screwed up–fire me. The system is that we hide everything we do wrong, from the line officers right up to the top.

“If you’re the chief of a law enforcement agency and are confident that everybody is doing everything by the numbers, you should welcome an independent review.”

Some form of independent review is needed in a situation like the Kao case to prevent bias among investigators and shore up public confidence in police agencies, says ex-cop Parker. “Police officers will try to support one another and cover for each other. That was my experience as a police officer–some officers will manipulate [the circumstances] and cover [for their peers].”

From the May 29-June 4, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

© 1997 Metrosa, Inc.