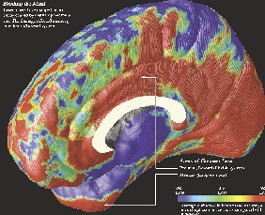

This actually is your brain on drugs: The shaded areas of professional brain imaging depict damage, not holes, in the gray matter.

By Patricia Lynn Henley

No, methamphetamine doesn’t cause holes in addicts’ brains; that’s a misunderstanding perpetuated by people untrained in researchers’ imaging techniques. And no, it isn’t possible to get physically addicted with just one use. But yes, the siren call of meth is so deeply seductive that many people get emotionally hooked on the drug after their first snort or puff, and physical addiction quickly follows. And yes, meth significantly changes the neurological functions of a user’s brain. Once an addict stops using, the body can usually repair the damage, but the healing process takes a long time, and not everyone returns to his or her previous level of brain function.

It’s important to understand the facts about meth, says Thomas Freese, Ph.D., director of training for UCLA’s Integrated Substance Abuse Program (ISAP), one of the nation’s main research centers on methamphetamine abuse. Although ISAP itself was founded in 1999, researchers working there have been studying meth since the mid-1980s.

“We know a lot about the neurocognitive and the emotional deficits that are caused by methamphetamine,” Freese says. “We can map the way that methamphetamine changes the way the brain functions. We have a pretty good sense of what it does.”

Methamphetamine is not found in nature; it’s created from manmade chemicals, including those in over-the-counter cold remedies, such as Sudafed or Contact. For the past 15 to 20 years, meth has been the primary choice for adult drug abusers in California and Oregon. In the last decade, the problem has spread nationwide.

While cocaine works between the brain cells, meth actually gets inside the cells and damages them. It takes at least a year or two of abstaining from the drug for the brain to heal from this assault.

“During drug use, many people report psychotic symptoms, particularly of a paranoid nature,” Freese explains. “For some people, those will remit over time, but for others it will be ongoing. Some will continue to have memory issues or mood issues or other mental health issues, like psychotic symptoms, that they hadn’t reported prior to their meth use. There’s no way to predict who [this will happen to].”

One of the unique aspects of meth is that it can be easily manufactured, using products from local pharmacies and hardware stores. “It does not require a chemistry degree,” says Beth Finnerty-Rutowski, ISAP’s associate director of training. “The average person can make it in their own home, which makes it significantly different from other drugs.” Increased restrictions on the common chemicals used to manufacture meth caused a lot of the large production labs to move south to Mexico, but meth remains easily available in California and nationwide, Finnerty-Rutowski says.

While addiction rates are soaring, this is a drug that can be beaten. “Methamphetamine is treatable,” Freese assures, but kicking a meth habit requires an intensive, months-long program, followed by aftercare that follows the addict periodically for at least a year, preferably longer. Meth depletes the body’s supply of dopamine, a pleasure neurotransmitter, which can cause a profound depression immediately after stopping use of the drug. In some cases, there can be ongoing clinical depression. It’s important that people understand the physical impacts of meth addiction, so that proper support can be provided. “For communities in general and treatment providers specifically, we can’t do enough to educate them,” Finnerty-Rutowski says.

Freese adds that addictions need to be dealt with as a chronic condition, not as an acute problem such as a broken leg. “Addicts need to manage their condition over their lifetime.”

Finnerty-Rutowski and Freese make presentations about methamphetamine facts and research worldwide; they will be in Windsor this fall, leading a day-long workshop titled “Demystifying Addiction: The Methamphetamine Epidemic.”

“Our goal is to help social services professionals, health professionals, community officials, law enforcement and educators,” says Susan Anderson, marketing director for the Drug Abuse Alternatives Center (DAAC). “The more that these people know about methamphetamine and the challenges we are having, the better we all are as a community.”

Parents of addicts or anyone else wanting to know more about this drug are welcome to attend, says DAAC executive director Michael Spielman. There will be specific breakout sessions on meth and HIV, meth and pregnancy, and prevention.

“They’re hasn’t been an all-day conference in Sonoma County focusing on methamphetamine for as long as anyone can remember,” Spielman says. “We felt it was time to bring the whole community together–educators, employers, human resource professionals, lawyers and more–to understand the scope of the problem.”

Beth Finnerty-Rutowski and Thomas Freese appear in Windsor on Sept. 12, leading a daylong workshop, ‘Demystifying Addiction: The Methamphetamine Epidemic.’ For registrations details, call 707.571.2233, ext. 311, or e-mail sa*******@******il.org.