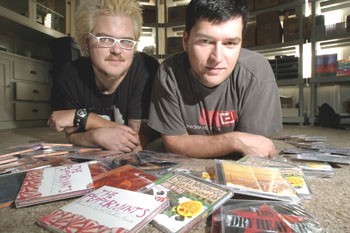

Photograph by Michael Amsler

The boys of Pandacide bring us music worth listening to.

The Sixth Annual Indy Awards

Showcases organizations new and old

By Davina Baum, Sara Bir, Gretchen Giles, and David Templeton

Each year there’s a moment of panic when we look back on the previous years of Indy Award honorees and wonder who, exactly, we’ll pick this year. like i said, it’s just a moment. then reality sets in. There are literally hundreds of worthy recipients, and we have to pick just five.

This year, we’re pleased at the variety the recipients represent, each doing their part to make the North Bay rich in arts. And remember: Next year there will be more.

Join us to fete the Indy honorees and celebrate the arts in the North Bay! The North Bay Theater Group will perform pieces honoring each of the recipients. There will also be ample amounts of accordion playing, opera singing, good snackin’, and general rabble-rousing. It’s free and open to all. Come to the Sonoma County Museum, Seventh and B streets, on Wednesday, Oct. 1, from 5:30pm to 7:30pm. (DB)

Josh Drake and Chris Ryder, Pandacide Records

Ask the guys of Pandacide what it’s like to run a record label and Chris Ryder–half of the team behind Pandacide–will say, “Ask him,” pointing to Josh Drake, Pandacide’s other half. Rumor has it that Josh does all of the work, while Chris manages to book all of the bands with girls.

Whatever the division of labor, Pandacide Records has grown from a vague idea in 2001 to a real-life label with eight releases and counting under its belt. And while there are a handful of scrawny yet noble record labels in the North Bay, Pandacide is probably the most ambitious in scope, releasing material by bands from all over the West Coast–or world, if you count Henry Fiat’s Open Sore, a Scandinavian punk band.

And it’s all right out of Petaluma, where Chris and Josh live in the Pandacide House and are employed at a lively health products distribution company–which is where the name Pandacide originated. “The name came first, from a tradition we have here where you go and write something on the white board, the most random thing you can,” Chris says. “We were talking about how nice guys finish last, and I made the comment how we were both panda bears, and so then it was just ‘girls commit pandacide.'” Uh, yeah.

So they had a name; all they needed was a mission, a way to contribute to the constantly evolving North Bay indie music scene. “It was going to be a zine, but we ended up getting the idea that it would be a promotion company and a booking agency,” says Josh, who wound up performing both duties anyway once the label was launched.

For three months, they sold buttons and T-shirts, but no records. Then Pandacide began booking shows, which is how the label picked up Asteroid Band by Sin in Space, a Pixies-esque band from Santa Cruz who played at Pandacide’s first show. Pandacide needed bands, Sin in Space needed a label. Voilà.

Pandacide’s next release, a lovely 7-inch picture disc by the Velvet Teen, taught the forces behind Pandacide that, while indeed lovely, picture discs are very expensive to produce.

Pandacide has acquired a lot of its learning though such decisions–decisions that are initially cool but ultimately make no sense, businesswise. Consider, for example, the extra cost of producing an over-card to cover up the potentially offensive cover art for the Peppermints’ Sweet Tooth Abortion. Or that Sin in Space (who have a long-delayed split 7-inch with the Velvet Teen coming out soon) sadly went on to implode from an overdose of rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle.

So they live and learn, and put out some true underground gems in the process, stuff that warrants regular rotation in the CD player. Pandacide’s catalogue includes power pop (the Librarians), arty noise stuff (Archaeopteryx, Get Get Go), gnarly grrrl shack rock (the Peppermints), Mexican-American punk (Los Dryheavers), and video-game electronic music (Little Cat). There’s not really a Pandacide sound or a definitive type of Pandacide band. “It does mirror our CD collections in some ways,” says Josh, “because who listens to just one genre of music?”

At the core of Pandacide, it may be just Josh and Chris, but there’s a whole network of other folks who’ve been sucked in to help out. “It takes the help of everyone you know,” Josh says. “You need people to master, to record the songs, to do the artwork. You do end up enlisting the help of other friends–and labels.”

Also a tremendous assistance, locals Sara Sanger and Josh Staples have shared insight gained from running their own label, Flying Harold Records. “Like not do it at all,” says Chris.

True, running an indie record label out of your home, garage, or on the sly at work is not what most people consider fantastic fun. It’s a lot of effort for virtually no money, a labor of love. “We can only do two releases a year,” Chris says. (Note: This year they have six.)

“We learned the lesson,” Josh says. “I swear we learned the lesson.” (SB)

Photograph by Rory McNamara

Michael Schwager brings us art from around the world and right close to home.

Michael Schwager, Sonoma State University Art Gallery

Finding a moment to catch Michael Schwager at rest is like trying to find a moment when an infant isn’t growing. The Sonoma State University art professor chairs his department, is the director of the prestigious University Art Gallery, and teaches art history and museum studies three days a week. He sits on the boards of both the Di Rosa Preserve and the Charles M. Schulz Museum, and was until recently on the board of the Sonoma County Museum.

Additionally, Schwager mounts five gallery shows a year, writes accompanying catalogues when he can squeeze in the time, directs the annual Art from the Heart fundraising bash, and is currently amid the daunting slate of special events that will comprise his gallery’s year-long 25th anniversary celebration.

Arriving at a Cotati cafe after class, at least one part of this energetic professor needs a break–Schwager’s voice simply gives out. But before the croaking begins, he is able to generously limn a career that began when he volunteered at the La Jolla Museum as an intern. Having gotten a degree in art from the California College of Arts and Crafts, he never really became the painter he thought he might be.

But working behind the scenes at La Jolla, he says, made him realize that there was an entirely fascinating level to the arts–not getting the paint to the canvas, but rather the canvas to the wall–that he had never before imagined. “I just thought, ‘Wow, what a cool world,'” he smiles. “It was suddenly my right place to be.”

From San Diego, he came to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where Rene di Rosa sat on his board (“We’ve come full circle,” Schwager says), acting as the exhibition coordinator there for five years. Schwager spent the next two years at the innovative Richmond Art Center and, feeling restless, casually answered a help wanted ad in a magazine. In early 1991, much to his own modest surprise, he got that job, as the director of SSU’s University Art Gallery.

Within the year, the school had added a course load to the job description. “I panicked, of course,” he chuckles, “because I’d never taught before.” Figuring that keeping organized enough to stay ahead of his pupils was the key, Schwager quickly got comfortable in the classroom. “I love the conversation about art,” he says now. “Teaching is one of those great times when there are no phones, and there is this wonderful convergence with the students of what they want to say to me and what I want to say to them.”

Schwager is widely credited with creating an outstanding atmosphere for aspiring museum staffers, producing roughly 90 percent of his gallery exhibitions through collaboration with his students, many of whom have gone on to work with major institutions throughout the United States.

Gay Dawson, executive director of the Sonoma Museum of Visual Art, says, “Michael teaches an arts administration class that has basically produced a large percentage of the arts administrators and support staff in the region; most of the people I hire come from him. He really cares about artists and he really cares about art.” Later she reflects, “He’s the type of person you want to work with. He’s kind and devoted to the arts, and he’s generous.”

Over the past 12 years as gallery director, Schwager has showcased emerging German artists, even coaxing them all to travel to Sonoma County, and has repeatedly made certain that residents of the North Bay have access to free exhibitions of work by such art stars as Jean-Michel Basquiat, George Baselitz, Enrique Chagoya, Ed Kienholz, Willem de Kooning, and Kiki Smith, to name just a small handful. Because while the gallery is certainly for the students and faculty of SSU, it is just as certainly for the rest of us too.

“I’m not interested in making us the most wonderful institution in the North Bay,” he says. “We’re part of a group of wonderful institutions. But we’re not just for the students, though they’re our primary focus. We’re here for the community.” (GG)

Photograph by Judy Hardin Cheung

The Wow! Art Salons encourage eclectic conversations about art.

Wow! Art Salons

Seven years ago, a Novato-based art aficionado named Angar Mora stepped reluctantly into the limelight to conduct a quirky little artistic experiment. Seeking a way to “woo the imagination” (those are his words), Mora, originally from Denmark, launched a miniature cultural revolution modestly dubbed the Wow! Art Salons.

Wow is right.

Mora’s innovative art-themed mixers–commonly referred to as “the Monday night salons”–have since gone on to become a certified North Bay institution, a vast, artistic collaboration that has involved countless artists and performers from across the Bay Area and beyond. Boasting provocative weekly themes (“Gravity of Reality, Lightness of Imagination,” “Wind, Ocean and Sailing Machines”) and drawing a cross-pollinating array of art makers and creative thinkers, the Wow! Art Salons are a unique and valuable oasis in the wild and wooly North Bay art landscape.

So then, what’s an art salon?

Imagine an elegant, reasonably priced dinner among friends and new acquaintances, all of whom share a love of painting, sculpture, photography, music, and fine conversation. Imagine that the room is crammed with interesting original art and that the artist responsible for those pieces is sitting right across the table from you, asking you to pass the bread before launching a spirited discussion about cultural elitism or freedom of speech or the appropriate use of deep focus. Toss in a lively Q&A session with said artist, a quick art auction, a short “art swap” period, then wrap the whole thing up with a bit of delightful jazz by an up-and-coming quartet.

That, in a nutshell (probably a hand-painted one) is the Monday night salon. Held regularly in a backroom at Cafe Arrivederci in San Rafael, the salons have become a dynamic demonstration of how food, art, music, and storytelling can be thrown together in ways that stimulate discussion, build support for the arts, and encourage collaboration. Collaboration, it turns out, is the vital element on which the salons have been thriving.

“The art salons are not about individuals,” explains Mora. “This project is about group effort, it’s about collaboration and cooperation, which I think are inherent in the art process. When you think about it, there’s not just a painter in the process. There’s a viewer too, to make the painting complete. I see the art evenings the same way.”

Mora, who acts as the moderator and host for the Monday evening salons, is not an artist himself. He’s more like a cheerleader, expertly whipping up enthusiasm while shifting focus away from himself and onto the people who do the hard work of making amazing art. “I see myself as a catalyst, not as a doer,” Mora says.

While the salons are plenty of fun–and popular enough that reservations are required (call Mora at 415.897.7313)–there is a more serious, and more ambitious aspect to the whole Wow! experience: that is, Mora’s successful efforts over the years to distribute and display new art in Bay Area restaurants.

“We have about 15 concurrent exhibits going on at any given time,” Mora says, adding that Wow! puts up about 250 exhibits a year. Let’s do some math. If you take the restaurant exhibits, held in various restaurants including Cafe Arrivederci, and you add the Monday evening art salons, which involve approximately 100 visual artists a year, then you can conclude that over a thousand artists have been brought to public attention over the last seven years. The restaurant exhibits are a deliberate attempt to bring the work of important living artists into contact with the people who are in the market for some art but didn’t know it until they went out to dinner.

“I don’t think a lot of people go to galleries,” says Mora. “I think collectors go there. As a standalone retail situation, the gallery is not a very viable option. It’s like church. If people aren’t coming to the church, you have to take the message out to where the people are. And we’ve found that, for the most part, the people are in the bars and restaurants.”

Art and music, Mora likes to say, are “gifts for our imagination–“imagination” being the key word. A piece of art, whether its a song or painting, is an expression of the artist’s imagination. But it is also an opportunity to fire up the enthusiasm and imagination of the viewer and the listener. So a partnership is formed when both the artist and the audience have a creative experience.” (DT)

Photograph by Michael Amsler

Michael Savage, as executive director of the Napa Valley Opera House, has led Napa’s beautiful new arts venue to completion.

Napa Valley Opera House

The fanfare surrounding the opening of the Napa Valley Opera House’s main stage this past August was all-consuming, extensive, and entirely deserved.

On Aug. 1, 2003, the Margrit Biever Mondavi Theatre stage brazenly pulled up her curtain for the public, revealing her wares. Stepping onto the meticulously reproduced stage was doyenne of screen and stage Rita Moreno.

After decades of work by tireless, dedicated fundraisers, Napa has a new arts venue, and the incredible theater is injecting the oft-maligned city with a fresh vibrancy. Just 30 years earlier, the building had been slated for demolition, a shopping center proposed for the location. In fact, demolition was threatened a number of times in the long path to restoration.

In 1973 the building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Even then, progress was painfully slow, despite the fundraising work of volunteers Veronica Di Rosa, Tom Thornley, and John Whitridge, among many others, who were determined to restore the theater to its previous glory. In 1985 a nonprofit was formed to raise money; in 1997 the facade was restored. Just last year the downstairs Cafe Theatre was opened, an intimate stage that offered just a taste of what was to come.

This second act, as it were, comes 123 years after the first opening, in 1880. The original theater was built by George “G. W.” Crowey, its Italianate facade designed by the Newsome brothers and local architect Ira Gilchrist. It cost $30,000 to build, and because Crowey didn’t believe that he would make enough money, he installed three retail stores on the building’s first floor.

A lot of things are different this time around, including the $14 million price tag, but a lot is the same. Executive director of the Opera House Michael Savage notes that “the theme throughout [has been] to try to do as much as we can that’s original.” So the atmosphere of the theater is old-world, with its swooping curves and warm colors. The upper balcony is the original wood, left unfinished so as to showcase its age. Meanwhile, the backstage machinations are entirely modern. The sound system is state-of-the-art, and the orchestra pit is modular to allow for different configurations depending on the needs of the production.

The productions, too, have some similarities. The first show to take the stage in 1880 was Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore, traveling to Napa just two years after its world premiere in London. This year, Opera à la Carte’s production of the now-classic operetta once again rollicks on stage. And while performers like Luisa Tetrazzini, John Philip Sousa’s band, and Jack London aren’t around now to entertain, the Opera House has managed to schedule a diverse array of talent, including performances by the Vienna Choir Boys, Taylor 2 dance company, and Wynton Marsalis.

Savage says that the model for the current slate of performances is series like Cal Performances in Berkeley, which covers a range of genres. “The aim is to bring in really top-quality shows, people like Dianne Reeves.” (Reeves inaugurated the intimate downstairs Cafe Theatre, which will now serve as a piano bar and reception area.)

The original Opera House had high ambitions, too, but circumstances led to the theater’s closing in 1914. Vaudeville theater didn’t have the draw for audiences newly smitten with the magic of the movies, and the theater had been damaged in the 1906 earthquake. Now, however, there is a palpable need for arts venues and an audience to fill them. (DB)

Photograph by Rory McNamara

Doug Bowes (foreground) and the Occidental Community Choir’s focus on original work has made them a local gem.

Doug Bowes and the Occidental Community Choir

I can’t say we’re the only choir around that does all-original music,” says Doug Bowes, director of the boundary-busting, aurally outstanding Occidental Community Choir, “but we are the only one I know about.”

Founded in the winter of 1978 when a group of folks met in downtown Occidental to sing Christmas carols–and decided then and there to never stop–the OCC, which Bowes “inherited” in 1988 from longtime director Allaudin Mathieu, is indeed one of the very few community-based choirs devoted to the composing and performance of new works. Almost all of these are written by members of the 40-person choir. Compared to most choral ensembles, the majority of which draw from the vast, rich tradition of classical choral music, the OCC’s embrace of original material marks a radical departure.

“We’re part of that classical tradition, somewhat,” allows Bowes, “but we also draw from the traditions of the theater–not that we do theater, per se, but like a theater company, every season we work to create a brand new show, pretty much from scratch. We do original choral pieces, though some are based on classical texts and oriental poetry, etc. We experiment a lot. We’re definitely different.”

To get a sense of just how different, check out the group’s website (www.strattonslater.com/choir) and take a gander at the official OCC group photo, in which the choir is bedecked in a Halloween party’s worth of weird getups, with the head of Doug Bowes apparently in the clutches of a baton-waving gorilla. As for the material the group performs each spring and winter, says Bowes, “Some is brand-new, composed specifically for that concert, and some is older material that was composed by choir members in the past, used in shows from a few years ago and rotated back into the lineup.”

Bowes, 55, a classically trained musician and composer born in Toronto, is himself responsible for a good number of the pieces the choir performs, having added (at last count) about 115 pieces written in a variety of styles. While much of the OCC’s “all-original” thrust is spurred by Bowes’ own devotion to the crafting and proliferation of new musical works, the OCC’s orientation away from the classics began, in part, with Bowes’ predecessor, composer-author Allaudin Mathieu, whom Bowes counts among his great musical heroes.

“Allaudin always wanted to do concerts that were about the place we live, about Sonoma County,” says Bowes, explaining that original material had already begun to be performed by the choir, but it was always blended in with more traditional choral pieces. “The last year that Allaudin was the director,” says Bowes, “his dream of doing a show about Sonoma County actually happened. It was called ‘Music from Home,’ and it was the first concert the OCC did that was all original material.”

Bowes took over the choir the following year when Mathieu stepped away to concentrate on other projects. He quickly suggested that the group continue the focus on all-original music, and aside from one or two Christmas carols during the holidays (hey, that’s how the whole thing started, right?), the OCC has devoted itself to the original-music cause. In so doing, the choir has earned a devoted following, music fans with a taste for on-the-edge compositional derring-do. How about an eight-minute, Mozart-inspired opera based on the story of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer? Or a complex choral piece, fusing bits of traditional parent-to-child advice (“Eat your vegetables; go to bed; no, you cannot get a small tattoo”). The OCC has developed and performed those pieces, and hundreds more.

Additionally, in morphing into a choir devoted to original, self-generated material, the OCC has become a kind of movable workshop for what might turn out to be a new generation of composers.

“It helps,” says Bowes, “that we always have a finite goal–the concerts. And it’s meant that anyone in the group who’s a writer–especially a novice writer–actually gets the opportunity to hear what they wrote, and to evaluate it and see if it worked or not. And yes, sometimes we present a piece that, um, doesn’t quite work.”

It’s not easy coaxing so many singers to take the leap into the composer circle, and it requires a safe, supportive atmosphere, with an emphasis on creative risk-taking.

“It’s a very collaborative process,” Bowes says. “What’s so wonderful is that, over the years, the OCC has seen the emergence of a number of incredibly good composers.” (DT)

From the September 25-October 1, 2003 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.