the arts | visual arts |

Reason of dreams: Goya’s ‘Sleep of Reason’ etching raises monsters.

By Brett Ascarelli

It wasn’t until 1983 that contemporary artist Enrique Chagoya touched a Goya print for the first time. He wasn’t surprised that it touched him right back. “You see the aquatint,” Chagoya explains, “and you see the super-fine lines that Goya did. It blows your mind.”

Goya, the Spanish painter and etcher, made modern art during the 18th and 19th centuries, well before what we commonly think of as modernism splashed into the shared psyche. Among his best-known paintings are The Third of May 1808, which depicts the French brutally gunning down a Spanish rebellion. But the artist also carved his mordant point of view onto copper plates, producing thousands of impressions that have since worked their way into the consciousnesses of a host of modern artists–among them, Chagoya.

“With Goya,” says Chagoya, speaking by phone from his San Francisco home, “I just imagine someone who’s very frustrated with his times, maybe someone who’s very angry with his society. I just wish I could have met him.”

Although meeting face-to-face is a chronological impossibility, the works of Goya and Chagoya will spend nearly two months together, from April 14 to June 10, when the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art (SVMA) exhibits the entire set of Goya’s Los Caprichos rare first-edition etchings. Chagoya’s eight-etching response, “Return to Goya’s Caprichos,” and a 1920s drawing by Edward Hagedorn will round out the exhibit, as will selected examples from some of Goya’s other graphical bodies of work, including Disasters of War.

A major coup for the SVMA, this very sexy and passionate exhibit was only able to happen because a lot of unsexy things did. The museum, whose mission statement includes a commitment to showing world-class art, had to start planning for this exhibit two years ago. Thanks to a major renovation completed in 2004, the museum now has a lot of very dry, very procedural assets–namely, precise control over lighting levels and environmental factors–that are often requisite for a show of this caliber, as with the Rodin exhibit that came through in 2004. “It’s not a cheap exhibit,” laughs SVMA director Lia Transue, noting that the museum was obliged to pay a participation fee to get the exhibit and shell out for an extra insurance rider. This will be the show’s sixth stop on its international tour.

Goya created the 80-piece edition Los Caprichos, or The Caprices, at the very end of the 1700s as a flinty sociopolitical commentary on the rude vices of his native Spain. The dark, finely etched prints go beyond just depicting the usual religious sins of vanity and greed, and also deal with provincial suspicions and elaborate an unearthly culture of monsters and witchcraft. A diabolical province of humans, beasts and in-betweens emerge from the shadowy prints in dramatic chiaroscuro. Shawls shroud downcast women, causing them to resemble faceless grim reapers; sharply dressed donkeys read books; winged monsters clip each other’s toenails. While many of his contemporaries had latched on to the beautiful muck of romanticism, a movement that stretched from the late 18th century to the early 19th century, Goya was drawing his nightmares and lamenting the passage of the Enlightenment.

Art historians argue about the facts of Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes’ life. What we don’t know, for example, is why, when his body was exhumed in Bordeaux to be repatriated some seven decades after he died, there were two skeletons in his grave, but just one skull. We also don’t know the exact circumstances around Los Caprichos. Why did he sell them at a scent and liquor shop in Madrid instead of at a more traditional bookstore? And why did he withdraw thousands of the prints from the market, just after releasing them? Was it because they were too dangerous, as some art historians think, or because they were a commercial flop?

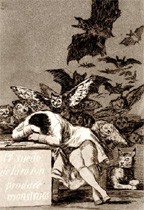

In print number 43 of Los Caprichos, Goya portrays himself asleep at a desk with bats and owls circling his head and the inscription “El sueño de la razon produce monstrous.” Did he mean “The sleep of reason produces monsters” or “The dreams of reason produce monsters?”

We do know some facts. He was born in Fuendetodos, Spain, in 1746, to a moderately wealthy family. He grew up in Zaragoza, Spain, and his nascent artistic inclination was at first denied outlet; the Spanish Royal Academy for painting rejected him twice. Finally, he placed second in a painting competition in Rome, and at 25, painted a cupola in Zaragoza. He began studying under Francisco Bayeu y Subias, who was a member of the Royal Academy of San Fernando in Madrid, and with Bayeu’s help, began drawing cartoons that would be turned into tapestries for Spain’s rulers through the Royal Tapestry Workshop.

At 37, Goya’s career officially launched when he painted the portrait of the king’s friend. Climbing the courtly ladder, he did more and more portraiture for the aristocracy and the royal family. But in 1792, an intense and prolonged fever left him deaf. While he had already showed a critical eye before his illness, the deafness only intensified it, shutting him into a solitude that incubated the ideas for Los Caprichos.

“He was a genius before,” says Robert Flynn Johnson, who wrote the exhibition commentaries and is also chief curator of the Legion of Honor’s Achenbach Collection. “But cutting him off of the world completely–if you want to get a sense, turn on Jay Leno at night but without the sound. You’ll see gestures and mugging. Goya’s whole world became a visible world without audio. Goya’s imagination and his already slightly bitter sensibility was heightened by this isolation.”

In the prints, Goya criticized what he saw as Spain’s backward practices, ranging from how men and women manipulate and abuse each other, to the uselessness of the nobility and the waywardness of the clergy. Only the poor were exempt from Goya’s discerning eye, but not the illogical superstitions that they held dear.

Goya released Los Caprichos in 1799, but they weren’t popular. Of some 300 sets, he only sold 27. “It’s like me,” Johnson, who has a fondness for making analogies, says, “making up a set of prints antagonistic to hunters and then trying to sell them to members of the hunters association. Quite frankly, he was biting the hand that fed him.” Most likely realizing that he would never be able to publish critical prints again, Goya nevertheless continued to etch, making three subsequent portfolios that were only published posthumously.

The same year he released Los Caprichos, Goya was appointed as the court’s foremost painter. This was remarkable. “It’s like if Howard Stern,” reflects Johnson, “were the chief of protocol at the Bush White House and was still doing his radio program.” Adeptly moving in and out of the two worlds, Goya had the chutzpah to schmooze for his living, then turn around and pan the society in his etchings.

“Nobody since Goya,” says Johnson, “has done a better or more thorough laying out [society, religion, social interaction and war] in visual art since that time. Since Goya, the only equivalent of his great war prints are photography–there are no paintings, drawings or sculpture that can compare.”

But social critique had occupied printmakers since the invention of the process, so what makes Goya so unique? “Before Goya,” says Johnson, “art was descriptive of the external world. If you were to describe an internal world, it was either a world of Christian sensibility or mythology. Goya made it possible for one to make visible one’s own personal, inner demons, disattached from religion or superstition. So Goya is the first great pre-Freudian Freudian artist, who allows the inner self to be made visible. That is a very important building block in the history of modern art.”

After Caprichos, Napoleon invaded Spain and brought the unenlightened chaos of the French Revolution with him. Goya continued painting whomever was in power. But by 1814, Spain had gone topsy-turvy, with the new monarch reinstating the Inquisition and trashing the country’s Constitution. Goya found himself out of a job.

Between 1810 and 1820, Goya made the Disasters of War series of 85 etchings and retreated to his country house, nicknamed the Quinta del Sordo, or the Deaf Man’s House. There, he made what are now referred to as his “Black Paintings,” which inspired the expressionists over a hundred years later. Among the black paintings are the gory Saturn Devouring His Son, titled after Goya’s death, but probably representing Spain’s civil strife, rather than mythology. Eventually, the conflicting political allegiances that Goya had pledged over the years made him unpopular, and he died in exile in Bordeaux.

(Even after his death, his prints still weren’t immune to the mercurial politics of Spain. Franco actually put his own stamp on the Goya prints that were hanging in the Prado.)

“Goya’s focus toward the end of his life,” says art history professor and di Rosa Preserve curator Michael Schwager, “was on expressing his own emotions and basically making paintings for himself without regard to who might see them or want them. This wasn’t something many artists did before Goya, and it became one of the hallmarks of modernism–art for art’s sake.”

More hellish than bats?: Chagoya’s response to Goya’s ‘Dream.’

Some two centuries separate the master painter from Enrique Chagoya, known for his subversive, cartoony and collaged images. Yet, the two artists are connected. One of the quirkier links is that Goya’s name is embedded in Chagoya’s, something which the contemporary artist plays with when signing his Goya-inspired prints: “Cha Goya.”

As a kid growing up in Mexico, Chagoya, who immigrated to the United States, in 1977, had read books about Goya but had never actually felt a Goya in real life. But while taking Johnson’s history of printmaking class at the Legion of Honor, Chagoya got to handle some of the original prints. Inspired, Chagoya made a modern-day takeoff on one of them, Against the Common Good, which features a demon writing in a book. Copying Goya’s technique, Chagoya made an etching that mirrored the original print, but instead of incising the old demon’s face, he replaced it with Ronald Reagan.

The pastiche was a hit in class. Johnson bought one for himself for $40 and purchased another for the Achenbach collection. Now, the L.A. County Museum, the National Museum of American Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art own Chagoya’s work, and his prints sell for thousands of dollars.

Driven to the Caprichos by the 1990s farcical political scene, Chagoya re-rendered Goya’s prints to include Jerry Falwell, who railed against the “gay” purple Teletubby, and Jesse Helms, who pushed the NEA to stop giving grants to individual artists because the NEA-funded artist Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ was too much to bear for the religious right. To Chagoya, these events and policies were as unenlightened and superstitious as those Goya depicted, so the modern artist inserted Falwell and Helms into Goya’s print of two devils giving each other a pedicure.

Targeting xenophobia and other evils, Chagoya made prints that updated Goya’s demons. The spooky bats and owls that Goya etched in print 43 of Caprichos, for example, aren’t scary to a modern sensibility. “Bats are good for agriculture,” says Chagoya, “and eat tons of insects–they’re the most organic pesticides. The owls are endangered species and people love them.”

So instead, Chagoya depicted Tomahawk missiles and Apache helicopters. “Imagine Baghdad under fire,” Chagoya says, “and you don’t know where to hide for a whole night, weeks, months, years. That’s worse than any bat or devil. We’re worse than any devil cheating you to get your soul to Hell. In this case, you send people to Hell, whether or not you have any thought. To me that’s Hell. And to me that’s the sleep of reason today.”

The Los Caprichos exhibits April 14 through June 10 at the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, 551 Broadway, Sonoma. On April 12, Robert Flynn Johnson lectures on “Francisco Goya; His Modern Sensibility,” at 4:30pm. $10-$15. On May 11, art historian Ann Wiklund presents “The Paintings of Goya: From a Terrible Truth to Madness” at 7pm. Free. Hours: Wednesday through Sunday, from 11am to 5pm. $5-$8; Sunday, free. 707.939.7862.

Museums and gallery notes.

Reviews of new book releases.

Reviews and previews of new plays, operas and symphony performances.

Reviews and previews of new dance performances and events.