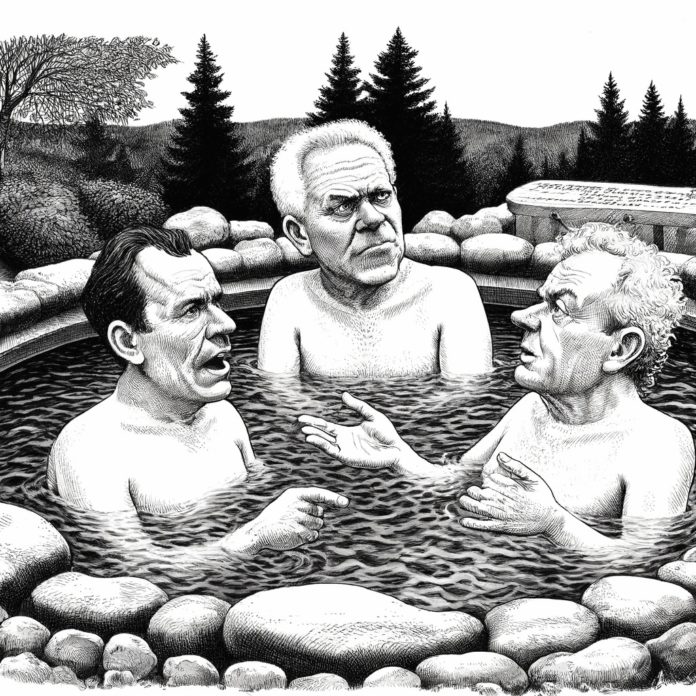

There were two men in the hot pool with me: One was a middle-aged white man like myself; the other, hoary, wiry and regal in the manner of a mad Shakespearean king.

His eyes sparked with electricity—a dangerous quality, considering we were sitting in water. I never learned his name. To me, he was Lear.

I’d eased myself into the water and their conversation. It was a mistake. They were talking about the election and, worse yet, in cheerful tones.

We’d all just entered the strange and liminal time between election and inauguration. The side I’d chosen had lost. Badly and decisively. Pickup trucks cruised through downtown Petaluma, flying giant “Trump Nation” flags. It seemed a grim confirmation that the America I thought I’d known was gone. But the election had just been the foreshock; the earthquake wouldn’t start until Jan. 20, 2025. The “one really violent day” that Trump promised was yet to come. Probably that was a bluff. Probably.

I’d decided to take a mental health day for this and other reasons and to spend it in a place I thought of as an ultra-left bubble in a bubble—my hippie nudist retreat in the liberal Bay Area in the left-leaning state of California.

But in the hot pool, I sighed and asked, “Are we discussing politics?”

Lear looked me over and replied, “Yes, we’re talking about Donald Trump. Did you have something to contribute?” He was a commanding presence, even naked. Perhaps especially naked.

Well, yes, I had thoughts. I recently posted this on Facebook: “Every four years we flip a coin. If it’s heads, we get a $20 Starbucks gift card. If it’s tails, we get terminal cancer.” I’d thought Harris was the gift card—not a revolutionary, just someone to keep the lights on until the next coin flip for democracy. Most understood the joke, but I had to clarify for a few concerned friends that I was healthy and was referring to the cancer on the body politic.

How to respond to Lear? I considered my words, the possible outcomes. None seemed good. “There are a lot of problems in this country,” I began. Safe enough. “And I think Trump will only add to them.”

The magician Penn Jillette worked with Trump and had this to say: “However bad you think he is, he’s worse.” But I honestly couldn’t imagine thinking any less of the man. All of the qualities that I value—intelligence, honesty, empathy, humility—seemed to me to be utterly absent in the person of Donald Trump. And his policies, his lawlessness, worried me even more than the man himself.

Lear and I sparred, eventually landing on policy. “Why not cut the Department of Education?” he asked me. “Just leave education up to the states?”

A complex topic. I gathered my thoughts, preparing to point out the hypocrisy of the GOP’s argument to “move education back to the states” when they’d imposed a SALT cap in Trump’s first term that punished residents of high-tax states, especially working people like myself.

Fine, slash the federal government. I no longer cared if Kentucky replaced science education with Bible study. I was in the process of a divorce myself, and my marriage had never been as adversarial as the one between red and blue states. I saw the benefits of separation; I just didn’t believe that Trump and the GOP were guided by principles of fairness, and I had the tax bill to prove it.

But I only got out the words, “I don’t really care if my taxes are going to the federal government…” before he interrupted. “To kill Palestinians?” he grinned victoriously.

He’d outflanked me, and with a vicious non sequitur. Say you’re concerned with Israel’s actions and the plight of Palestinians. Why then support an Islamophobe who calls himself “the most pro-Israel president in American history”? And anyway, what did this have to do with public education?

“Now you’re putting words in my mouth,” I said. It was as good a rejoinder as I could manage. There was now blood in the sacred healing waters. We were at a retreat center dedicated to “the practical, living embodiment of oneness,” but it seemed possible that this argument might end with one of us drowning the other.

Lear pressed on. “Child trafficking is a real problem in this country,” he continued, “and Trump will put an end to it.”

A moment ago, I’d decided to stop engaging with him, but the absurdity of this statement broke my resolve. At that time, Donald Trump had just nominated Matt Gaetz to be his attorney general, a man literally under investigation for the sex trafficking of a minor. And of course, Trump himself. “You mean Jeffrey Epstein’s best friend?” I asked. The words slipped out, delaying my escape.

He paused. I’d finally scored a point. The third man in the pool gave me a smile, as if to indicate we shared at least an adjoining reality. “That’s just hearsay!” retorted Lear.

I thought of mentioning the recording of Epstein saying just that, but no, I was done. Leaving the pool, I offered up a rhetorical olive branch, attempting to relieve the tension: “Who knows what the truth is anyway?”

He took my olive branch and slapped me across the face with it. “I do,” he insisted. “I know what the truth is.”

“Sure you do,” I muttered, dripping my way toward the quiet pool. Steam rolled off my skin and likely out of my ears.

Why had this interaction surprised me? The extremes of political ideology resemble each other more than either resembles the center; that’s basic Horseshoe Theory. Rednecks with Confederate flags and naked hippies were both Trump’s natural constituency. He was the counterculture, a breaker of norms.

But it wasn’t my political differences with Lear that bothered me; it was the epistemological ones. The argument over truth and belief.

You know the problem. Two doors, one to freedom, one to death. One guard who always lies, one who always tells the truth. The solution seems obvious when one guard proclaims, “Windmill noise causes cancer” and “We’ll wipe out our national debt with a little Bitcoin.” Then your teammates point and shout, “That’s him, that’s the one who always tells the truth!” and you’re dragged toward what’s obviously the wrong door.

That is what America feels like to me right now: a $6.2 million dollar banana duct-taped to a wall, all reason suspended. Avian flu outbreaks increased the price of eggs, and in response, we gave the nuclear codes back to Trump, whose former chief of staff, Gen. Mark Milley, called “the most dangerous man in America.” Lunacy.

I remembered the play Rhinocéros, written by Eugène Ionesco in 1959, as an allegory of rising fascism. In the play, a society crumbles as its citizens turn one by one into rampaging beasts. They stampede, lose their reason and speech, and literally become inhuman.

Bérenger, the last man left, has managed to hold onto his humanity but at the cost of being utterly alone. He listens to their braying and laments: “Their song is charming—a bit raucous perhaps, but it does have charm! I wish I could do it! … I’ve only myself to blame; I should have gone with them while there was still time. Now it’s too late!”

My alienation and paranoia were growing. Was that muscular and trim man to my left sporting a swastika tattoo on his arm? Were the acronyms inked into his skin white power sigils? I looked away; I didn’t want to know. I wasn’t capable of that conversation, not then.

I found my way to a sitting area beneath the roots of a fig tree that spilled down into a waterfall of wood. The roots intertwined, making phantasmagoric and sinuous figures—sensual, horrific, peaceful. And nothing more than roots as well. There I sat and looked and felt the weight of history.

A few days before, I’d listened to a former ICE director give an interview on Trump’s planned mass deportation. It made me think. My Jewish-European grandparents were brought to America as children back when immigrants were welcome. They’d entered officially through Ellis Island. But what about their ancestors who’d come to Germany and Poland long before in search of a better life? Did they have the proper documents?

How were my distant Jewish-European ancestors so different from the immigrants in my country doing the jobs that native-born Americans generally won’t do, providing easy scapegoats for demagogues like Trump to accuse of blood libel and eating cats and dogs?

The electoral map had just been stained red. But if the Republican Party was still “The Party of Ideas” and “The Law and Order Party,” then they had lost because Trump and his allies clearly belong to neither. The true victors then are Republicans in Name Only. The RINOs have won.

Facing his own rampaging crash of rhinos, Bérenger overcomes his cowardly urge to join them. Defiantly, he delivers the final line of Rhinocéros: “I’m not capitulating!”

Sadly, I fear we’ve capitulated by degrees, acclimating to our rising political temperature in the years between Reagan and Trump. Perhaps now we are cooked.

Time will tell if we can recover from this. However it turns out, Bérenger had it right. Stay human, hold your head above the rising tides of fascism, and proclaim with him: “I will not capitulate!”

I will not capitulate- we are in scary times, but I will not capitulate.

The frogs may be out numb bering the remaining humans.

Thank you Scott.

Please know this: You are not wrong.

They say never read the comments, but I’m glad I did. Thank you fellow humans!

Ionesco’s Rhinocéros …

Our lives, imitating the absurd.

Quite enjoyed this piece. Looking forward to reading more of your writing. Have you e-archive?

Thank you Robert, glad you enjoyed it. What’s this e-archive?

It sounds like you did not “tke the bait”, I read while mentally coming up with cutting responses so I am glad I was not there. In my heart I want to try to address the polarizing issues with openness and compassion but it is hard to keep the voice of my radical humanitarian from screaming, “why can’t we truly care about the planet and the lives on it, why is greed the bottom line?” You were wise to change pools,rather than stay and soak in the muck.

I don’t disagree but I don’t get into conversations in our nudist club’s hot tub anymore because with all the pronouns these days I am afraid to offend anyone by getting them wrong, so I just don’t talk to anyone. The last person I tried to talk to chastised me for using “they” wrong, dressed down by people not wearing clothing…..It is so hard to be politically correct, how can everyone else use plural pronouns perfectly for the singular? My wife has never voted for a Republican, and is feminist, she would burn her bra but never wears one but lost her college swimming record to a biological male and as such she now wonders what feminism means? MAGA people ask us about what feminism is, pointing this out to her or me? We stay mum. We went to a LGBTQ church in St Petersburg last year, figure it was a sea of tolerance, Gosh, we can’t go to a regular church. We felt really comfortable and “came out” and admitted we were nudists during the meet and greet afterwards to the Lesbian pastor and her wife, she gave us a funny look. We came back the next weekend and were obviously shunned. Word had gotten out. I guess there is no room “N” in LGBTQ plus. I felt hurt. My wife felt rejected. When you cannot come out to people that are out who agree with 90% of what you do and it is still not good enough. We just do not say anything to anyone these days. I just watch as the right leaning folks I know have seemingly fun conversations and we stay mum, because we are afraid to talk to left folks and we can’t talk to right folks. What happened? I think I understand why people are attracted to the right, it is just so hard to be left.