It’s 2:30pm, a time Beth Hall calls her golden hour.

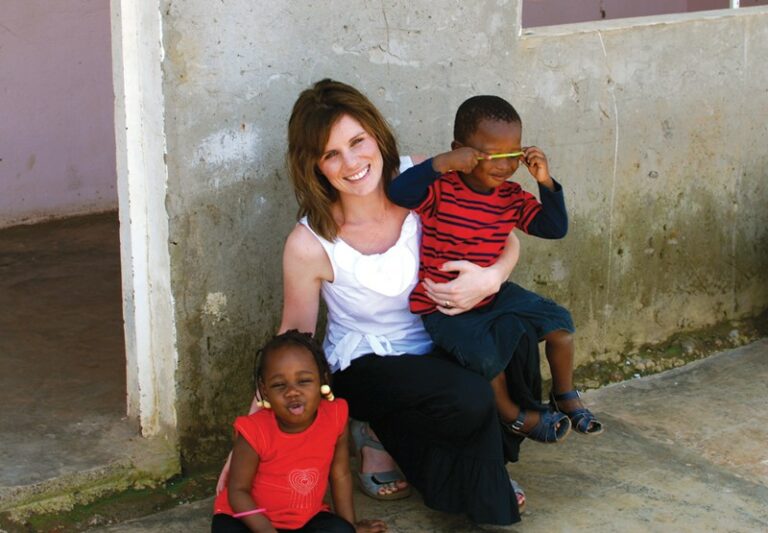

The reason is simple: her four-and-a-half-year-old Tyler is at preschool, and everyone else is down for a nap. That includes three-year-old Piper, 18-month-old Quinn and, as of this year, her newly adopted children from the Democratic Republic of Congo—three-year-old Grayson and two-year-old Charlotte.

From a bedroom down the hallway, we hear movement and a few cries. Hall pauses to listen.

“I gauge who’s crying to see how much work it’s going to be,” she says.

Four weeks ago, the Santa Rosa mom and her husband, Mike, came back from the DRC with the two new additions to their family. With five children under age five, two of whom only speak French, the experience has been compounded by the poverty and societal trauma that, until a month ago, was their adopted children’s present. And while this adoption no doubt marks a turning point for the two, it’s a transition that hasn’t exactly been easy.

Hall began considering adoption when she was told she might never have children, an assessment that obviously turned out to be wrong. But even with biological children, the couple knew it was something they wanted to pursue. When they began learning of the massively underreported conditions in Africa’s second-largest country, they turned their attention there.

Since 1998, the DRC has been the site of massacre and sexual violence so overwhelming that the few writers covering it tend toward comparison rather than digits. Incited by the same militant refugee group responsible for the Rwandan genocide, the First Congo War—sometimes called the African World War—involved nine countries, 20 armed factions and has claimed the lives of roughly 5.4 million people. A 2006 report commissioned by the UN relief effort UNICEF puts it like this: “[E]very six months, the burden of death from conflict in the DRC is similar to the toll exacted by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.”

Though the exact number of rape victims in this bloody travesty is unknown, the report estimates them to be in the hundreds of thousands. “Sexual violence is consciously deployed as a weapon of war,” it states. Abortions are punishable by imprisonment, and yet women and girls who are raped and become pregnant often become social pariahs, rejected by even their families, according to the document.

Considering all this, a scene witnessed by Hall makes tragic sense. She was in the DRC, in an area far from military occupation but still suffering from poverty that afflicts roughly 70 percent of the country’s population, according to Children’s Rights Portal.

“A mom walks by with four or five kids, and she’s holding a little three-month-old,” she recalls. “She comes up to us, to a man who was with us, and asks him to take her baby. She was serious. He very kindly said no, and so she asked again, pushing her baby toward us. She just looked like a mom. She just looked like a regular lady.”

Parents routinely abandon children they can’t care for in public places, Hall says, hoping desperately that something better than the life they themselves can give will come along. According to Children’s Rights Portal, the country is home to roughly 70,000 children living on the streets.

The new mom asks not to discuss what she knows about her children’s past, for the sake of their privacy. But she adds that she doesn’t know much.

“A lot of people will never know their kids’ stories due to the nature of the abandonment,” she says. “We hope to just give them a rich knowledge of their history, and to know that while they were not unloved, the hope is to give them a better life, or a life at all.”

Seated on her living room floor, Hall details the highs and lows of the family’s first tumultous month together, which she likens to a roller coaster.

“Adoption, especially international adoption, can be romanticized,” she says, “and while I really did not do that, it’s tough. They’re traumatized by their loss, and mourning as well as a two-and-half-year-old can.”

That morning, for example, Charlotte watched Hall put her shoes on and immediately started crying.

“I just took my shoes off, and I was like: ‘Mommy’s not leaving,'” she says.

But the high points are there, too.

“One moment can be so difficult, they act out all of their trauma on top of the trauma of just being three, and then the next moment they’re so sweet and you think they can’t get any more darling,” Hall says.

The Halls adopted through a faith-based organization called Compassion for Congo, and Beth recommends that parents trying to adopt internationally learn as much as they can about the organization they’re going through, to avoid bizarre situations enabled by language and cultural barriers and for-profit adoption agencies. In 2009, for example, This American Life did a story on a Samoan agency that took children from their families in what the biological parents thought was a boarding program, and the American parents thought was a done-deal adoption.

“Ask a lot of questions, not just of your home-study agency, but of where you’re getting the kids, because it’s easy for them to be very vague,” she says.

She also recommends that adoptive parents get as clear a picture of the foster home or orphanage as they can, and try not to be led by blind idealism. Reactive attachment disorder, which can occur when a baby or young child is passed between primary caregivers, is a psychological affliction that can come with abusive or neglectful homes, she says.

“It feels really good to look at such a huge problem like the Congo or abandoned children, and then to look in my kids’ eyes and say, ‘I cannot help all of them, but I can help you two,'” she says.