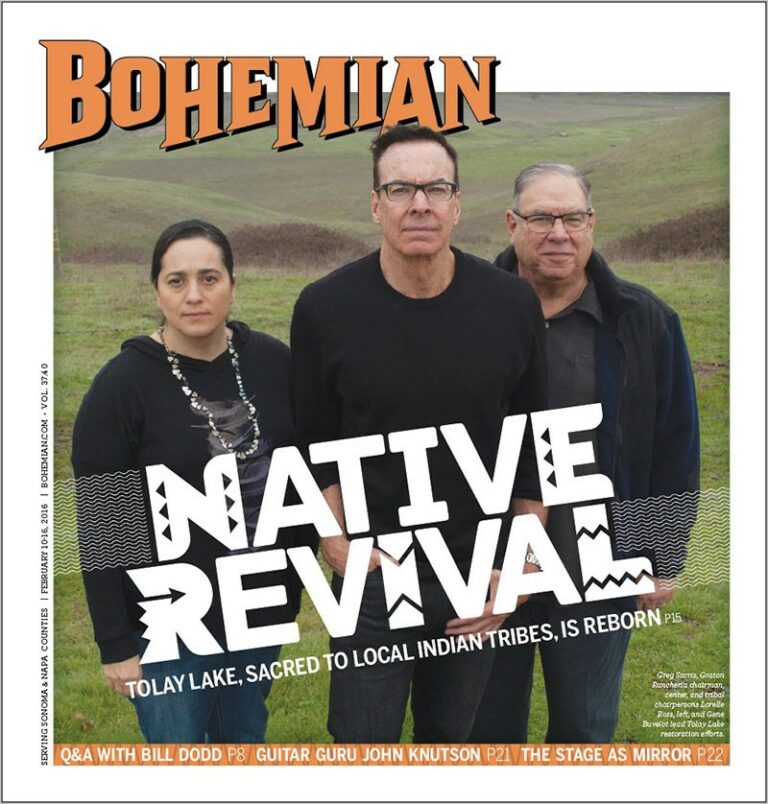

On the second day of 2016, I have gathered with Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria tribal councilmembers Lorelle Ross and Gene Buvelot to observe the southern view from the eastern ridge of Sonoma Mountain, about seven miles east of Petaluma. From this world-at-your-feet platform, the smooth blue expanse of San Pablo Bay rises against San Francisco’s Financial District, with Mt. Diablo and Mt. Tamalpais visible on the water’s fringes.

The main object of these indigenous leaders’ attention, however, is a far smaller body of water that historically occupied a 200-acre depression directly beneath the ridge. For thousands of years, this shallow lake, today known as Tolay, was a sacred gathering place for Coast Miwok people—including the ancestors of Ross and Buvelot.

The lake had been, as Graton Rancheria shairman Greg Sarris informed me, a Miwok version of Stanford Medical Center: a place of extraordinary healing power that called together indigenous people from throughout the region now known as the western United States.

In the late 1880s, however, an industrious farmer dynamited the southern berm that held back the lake’s water, draining it to San Pablo Bay. The land became gridded and platted with ranches, cutting off the indigenous people’s access to it.

This was one in a long line of deadly and devastating insults against the Miwok. When the Spanish arrived in the late 18th century, they introduced population-destroying diseases and incarcerated Coast Miwok and other California natives in crowded, disease-ridden labor camps at missions in Petaluma, San Rafael and Sonoma.

The Graton Rancheria’s membership, which includes descendants of the Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo linguistic groups, trace their ancestry to only 14 known survivors of Spanish and U.S. colonization. Their combined pre-contact population had been 20,000–30,000.

These cultures’ stubborn endurance, however, ensured that their connection with sacred places was not fully severed. Shortly after the Sonoma County Regional Parks department purchased 1,900 acres that includes Tolay Lake in 2005, the Graton Rancheria tribal council saw an opportunity—and took it.

The councilmembers borrowed $500,000 against their future casino and donated it to the county to support the park. In turn, they gained an influential role in determining everything from trail locations to the restoration techniques the county parks department will rely on to restore the area’s streams and vegetation, and the lake itself. For the Graton Rancheria Indians, the healing place of their ancestors has become an important communal gathering area, and a focal point of healing in an altogether more modern sense.

“If you don’t have a connection with the land, you’re lost,” says Ross, who has been a tribal councilmember since 1996, when she was 19 years old. “Now we have kids in our tribe who are growing up experiencing revitalization and re-engagement with this place their ancestors took care of.”

They are not alone. Throughout the North Bay, the North Coast and multiple other regions of California, indigenous people are reclaiming stewardship of ancestral territories from which they were once violently evicted.

PICKING UP THE PIECES

The struggle of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, as with any sovereign entity, has been defined by access to land. A major turning point occurred in 1851–52, when treaty commissioners, sanctioned by Congress, negotiated 18 agreements setting aside roughly 7.5 million acres of California territory as reservations for 500 indigenous nations whose ancestral land base was being overrun by gold miners and land speculators. But the Senate rejected the treaties and ultimately sealed them.

The documents were unsealed more than 50 years later. Amid the resulting public outcry, Congress provided a very modest form of redress, passing legislation authorizing the purchase of small tracts of land called “rancherias” on behalf of “the homeless Indians of California.” In the case of the Graton Rancheria Indians, a 15.5-acre rancheria northwest of Sebastopol was set aside for “the homeless Indians of Tomales Bay, Bodega Bay, Sebastopol, and the vicinities thereof.”

Before long, even this small vestige of the Graton Indians’ aboriginal territory was stripped away. In 1958, Congress revoked Graton’s federal recognition (and that of 39 other California tribes), auctioned most of the rancheria land and turned the residents out of their homes—part of a larger push to “terminate” Indian reservations and thereby hasten the people’s assimilation into the dominant U.S. society.

“We became like the white man: homeless in our own homeland,” Sarris, the Graton Rancheria chairman, explains.

Sarris is a man with an impressive résumé. He is a longtime college professor, author, Hollywood producer and screenwriter. He played a key role in his tribe’s restoration to federal status. In 2000, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Graton Rancheria Restoration Act, which Sarris co-authored. Formerly an English professor at UCLA, he is now the endowed chair of Writing and Native American Studies at Sonoma State University—a position funded by the Graton Rancheria itself.

That endowment, as with other tribal line items, is largely made possible by the Graton Resort and Casino, an $800 million monolith in Rohnert Park, on the west side of Highway 101, that opened in 2013. Though the casino originally faced an intense backlash from a segment of the local populace, it has earned support from many critics as the tribe’s intentions have become better known. The tribal council agreed to donate $12 million and

$9 million in annual revenue, respectively, to Rohnert Park and Sonoma County to offset its impact on public services.

Along with federal grants, the casino underwrites many social services for tribal members, including housing assistance, healthcare, nutrition and health counseling, a cultural resources library, a language preservation program, and more. Sarris says that, in contrast to the hospitality and wine industries, which he says generally exploit their workers, the casino was built and is operated by union employees who earn above living-wage rates. His tribe is also investing in ecologically minded farms that will employ undocumented people and, pending permission from the county, low-risk prisoners at living wages.

Amid this larger social justice agenda, the tribe is working to pick up the pieces of a shattered history—a history fundamentally tied to the landscape. Sarris notes that his people’s entire historical land base, including places like Tolay and the Laguna de Santa Rosa, are akin to their holy text. “Most of the Bible, if you want to use that analogy, has been destroyed—has been burned,” he says. “All we have are shards of the text, bits and pieces of it. Tolay Lake is a place where we can make a start.”

Currently, the park is only open for special events. It will likely open to the public in 2017.

[page]

RIGHTING WRONGS

Because indigenous cultures are inextricably linked to the lands they have historically inhabited, their survival necessarily depends on preserving those lands, which face countless threats at any given time. In California and beyond, contemporary indigenous people are engaged in battles over mineral rights, water rights, federal recognition, honoring of treaties, repatriation or honorable treatment of sacred sites, healthcare, language preservation and much more.

In California alone, there are 109 federally recognized tribes and another 78 that are petitioning the Bureau of Indian Affairs for recognition, often waiting for decades to receive a verdict. Many others do not bother to apply for recognition at all, often viewing it as a waste of energy and resources.

Beth Rose Middleton, associate professor in the department of Native American studies at UC Davis, cites several examples of how even indigenous people who lack federal recognition are finding ways to exercise sovereignty over their original territories. Middleton is the author of Trust in the Land: New Directions in Tribal Conservation, which explores conservation partnerships led by California native nations. In contrast to many conservation land trusts, which prioritize species conservation that diminishes human contact with land, she notes that Native American–led projects focus on restoring humans’ historical role as land stewards.

Such projects provide a tangible way “to right historical wrongs and provide long-term protection and enhancement of lands and waters we all depend upon,” Middleton says.

California’s first-ever indigenous land trust was born out of a figurative and literal battlefield in the “Redwood Wars.” In the 1980s, large corporate timber firms—including Louisiana-Pacific, Georgia-Pacific (now owned by the Koch Brothers) and Maxxam—were in the process of felling most of the largest remaining redwoods and Douglas firs on their private lands along California’s northern coast.

People chained themselves to trees in the heart of a roughly 7,000-acre parcel Georgia-Pacific was actively logging, located within the ancestral territory of the Sinkyone people. A lawsuit by the Arcata-based Environmental Protection Information Center, the International Indian Treaty Council and other parties halted the logging operation.

Those that protected the forest named the largest stand of old redwoods the Sally Bell Grove, after a Sinkyone Indian woman who had survived a massacre of her people as a young girl in the 1860s.

At the outset, many of the forest protectors—transplants from urban life and white, for the most part—might easily have viewed Sally Bell as a token of their struggle. They would soon find out that her legacy was very much alive. In 1986, seven tribes from Mendocino and Lake counties formed the InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council, with the intent of acquiring a portion of the Georgia-Pacific land for traditional cultural purposes.

After co-founding the Sinkyone Council, Priscilla Hunter of the Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians (a federally recognized tribe), and numerous others, led a political and fundraising campaign that involved grants and small donations. In 1997, the InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council land trust became the proud owner of 3,900 acres of rugged and beautiful Sinkyone terrain, establishing the first intertribal wilderness park in the United States.

The council’s current executive director, Hawk Rosales, notes that the Sinkyone has been a touchstone of a broader social movement, which focuses on restoring land to indigenous stewardship as a means of protecting the land from industrial activity, while also enhancing it through wise human intervention. “We have shown the world that there is a way in which indigenous people can, and will, return to their role of traditional caretakers on the land when given the opportunity,” Rosales says.

There are now at least four other indigenous land trusts in California. In Oakland, for instance, the first women-led, urban land trust in the country formed last year. The Maidu Summit Consortium land trust formed in the early aughts on behalf of Mountain Maidu people in the vicinity of Mt. Lassen.

The Mountain Maidu got their breakthrough in the wake of the early-2000s Enron scandal, which forced PG&E into bankruptcy. Since the early 1900s, the utility giant had owned title to one of the tribe’s most sacred areas, Humbug Valley, a miraculously undeveloped 2,000-acre meadowy area southwest of Lassen. As part of the bankruptcy proceedings, a state judge ordered the utility giant to relinquish thousands of acres it owned to conservation stewards.

In a lengthy process, Mountain Maidu traditionalists demonstrated to the court-appointed stewardship council their worthiness as stewards of their ancestral land. By 2013, the Maidu Summit Consortium had claimed title to the valley from one of the wealthiest and most powerful corporations in the western United States.

In 2014, Maidu Summit consortium executive director Kenneth Holbrook, a 40-year-old Mountain Maidu traditionalist with a broad and boyish smile, led me on a tour through Humbug Valley. It is a remarkably beautiful place, featuring a meadow fringed by tall conifers and a soda spring bubbling out of the ground on one end to help form Yellow Creek, a tributary of the upper Feather River.

In 1908, Holbrook’s great uncle was murdered by two California game wardens as he fished near there. Roughly a hundred years later, key support for the consortium’s stewardship proposal came from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, which regards Yellow Creek as one of the most promising areas in the state for native salmon restoration.

“We’re all hopeful that the song of the salmon will return to this valley under our people’s stewardship,” Holbrook says. “Getting the land is really the first step.”

Hawk Rosales says that recognition of indigenous people’s knowledge of tending the land has broad implications for environmentalists in general.

“Among various segments of society, I think we now see an increasing interest in restoring a better relationship with nature,” Rosales says. “But without key principles of ancient traditional tribal knowledge, which honor and protect the many complex interrelationships and functions of the natural world, then the well-intended efforts of non-native groups to restore environmental balance will only go so far.”

[page]

INDIGENOUS STEWARDSHIP

Sonoma County Regional Parks has developed a well-regarded process of consulting with local tribes. Its relationship with the Graton Rancheria in the management of Tolay Lake Regional Park, however, is entirely unique. “I think this collaboration is a testament to Greg [Sarris] and the tribe, and to the great working relationship we’ve had, even prior to the Tolay project,” says Sonoma County Regional Parks director Caryl Hart.

Much of that collaboration involves planning out the land’s restoration. A Graton Rancheria tribal citizen named Peter Nelson, a Ph.D. candidate in UC Berkeley’s department of anthropology, is playing a crucial role in that process. Nelson’s dissertation focuses on the history of human use of the Tolay Lake Regional Park land. “I’m basically speaking the language of ecologists and other scientists in support of what the tribe is doing,” Nelson says.

The area surrounding Tolay Lake now consists of open grasslands characterized by non-native annual species such as wild oat, which turns golden in the summer. The land is dotted with cow patties. According to Hart, the agricultural heritage of the land will remain a fixture of the park, allowing for limited grazing. At the time of European contact, the area remained green year-round due to the prevalence of perennial bunch grasses, which the cattle later trampled out.

Stands of gnarly live oaks occupy only niche habitats on the Tolay Lake Park grounds today, while they were far more abundant 200 years ago, Nelson says. Shrubs that were once prolific, such as California lilac and California coffeeberry, are now entirely absent. A variety of colorful bulbs, like those in the Brodiaea genus (a staple food source that California Indians actively cultivated), are now consigned to marginal areas.

This former abundance of vegetation depended on the Coast Miwok people’s tending practices, Nelson says, particularly their careful use of fire. In oak savannahs, fire removes oak leaves and litter, opens up the soil so that plants can grow faster, helps to control harmful insects and diseases, improves wildlife habitat (by, for example, removing brush from around water sources) and recycles nutrients from the litter into the soil. That resulting cornucopia of plant life, in turn, supports a greater array of wildlife.

The lake itself was also actively managed by indigenous people, Gene Buvelot tells me. Again, Nelson’s research reinforces traditional knowledge. He notes that ecologists and geomorphologists have told him that “the land formation of this valley should not naturally hold water, and there is no evidence of landslides, so there must have been a dam constructed by native people in order for there to have been a lake.”

Even after U.S. colonization, the Coast Miwok continued to conduct multi-day ceremonies at the lake. Warren Moorehead’s 1910 book, The Stone Age in North America, refers to a letter from Petaluma ranching pioneer J. B. Lewis: “When I came here in the early [1850s],” Lewis wrote, “there used to be large numbers of Indians who go by my ranch in the fall, down to the creek to catch sturgeon and dry them, and they always went back by the way of [Tolay Lake] and stayed a day or two and had some kind of powwow. After the lagoon was drained, they never came back.”

RESTORING WHAT WAS

When I visited Tolay Lake, the old lakebed—roughly 200 acres in size—held no standing water. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has developed a plan to restore it with the tribe.

“You can’t recreate what once was, but you can use the knowledge of the past as a baseline to imagine and create a space that is of the here and now, as a guide into the future,” Ross says.

After leaving Tolay Lake Regional Park, Ross and Buvelot led me on an eastern drive along Highway 37, around the base of Sonoma Mountain. Our destination was a 2,100-acre parcel the Sonoma Land Trust is donating as an addition to the park. Highway 37 itself, the “Lakeville Highway,” gets its name from the former town of Lakeville—which was named for Tolay Lake.

We stop at the Sears Point marsh on the edge of San Pablo Bay. As Buvelot notes, the area’s indigenous people formerly maintained themselves on sturgeon, Sacramento hitch and bat rays, which they fished out of the tidal marshes. The abundance of fish is a major reason Sonoma County was home to one of the highest concentration of indigenous people in the Western Hemisphere.

But the fish’s habitat was largely destroyed by dikes and dams along the bay’s fringes in the early 1900s. Starting in the 1980s, the Bay Institute and other environmental organizations adopted a program to restore 100,000 acres of these tidal wetlands, which has entailed buying the lands and removing the dikes. By 2006, the 1,000-acre Sears Point area was the proverbial “last hole in the doughnut,” the Bay Institute’s Marc Holmes, a wetlands-restoration expert, tells me.

Ironically, Graton Rancheria had purchased an option on the Sears Point property for $4.7 million, using an advance from their Las Vegas–based casino development funder, Station Partners. The tribe was exploring building its casino there. As soon as they learned of the conservation groups’ intention, however, they donated the purchase option to the Sonoma Land Trust. Finally, in October 2015, tribal members joined environmentalists and regulatory officials in a ceremony where the levy was breached, and water once again washed into an area of crucial habitat that had been drained and dried.

Buvelot is one of the most respected elders in North Bay Indian country. His memory is filled with landmarks and watersheds of his people’s historical occupancy of this region. On the way to the levy breach site, he points out a former village site, which the California Highway Department (now CalTrans) bulldozed to construct the highway.

Buvelot’s grandfather, the locally famed Coast Miwok fisherman William Smith, is largely credited with founding the Bodega Bay fishing industry in the early 1900s. He recalls being eight years old when the Highway Department built an extension of Highway 1 through Bodega Bay—and also through some of his people’s ancestral burial grounds—during the 1950s. As the relics of his ancestors were excavated and cast alongside the highway, he and his relatives scurried around shoving them into burlap sacks, hurrying before the bulldozers returned.

THE HONOR OR RESPONSIBILITY

As with the rest of Tolay Lake Park land, the Sonoma Land Trust’s new addition consists of beautiful rolling meadows. It sits at the crossroads of highways 37 and 121. And like so many parts of the North Bay, it is a place where industrial civilization’s imperative to expand visibly collides with the need to protect the earth from despoliation and greed. A sprawling new vineyard and a winery are slated for development on one side of the land; the Sonoma Raceway lies on the other. Hundreds of cars course past on Highway 121 in the half-hour we spend there.

Ross’ life, like Buvelot’s, has paralleled the larger journey of the Graton Rancheria people. Her grandmother was forced to attend an American-Indian boarding school in Sherman Oaks. When the original, Sebastopol-based Graton Rancheria was terminated, their family held onto a one-acre parcel where Ross’ parents raised her in a small cabin. She says the discrimination and racism she grew up with was more subtle than what her parents experienced.

“I feel like I get to live through a time when I have the honor of responsibility,” she says. “There’s not a bounty on my head. I’m not forced to stand at the back of the line due to segregation. It’s a different time. It wouldn’t be right if I didn’t take the privilege I have, which is born from the sacrifices of those that came before me, to try to advance our community.”