Nick Hornby examines dilemma of rock critics

By Gina Arnold

NICK HORNBY is the avowed hero of most rock journalists. Along with cartoonist Matt Groening (The Simpsons) and screenwriter Cameron Crowe (Almost Famous), he is one of the very few who have made good in another writing genre.

I’ve never met rock writers who didn’t think they had the great rock novel up their sleeve, but Hornby’s High Fidelity came closest to making the grade. Normally, writers feel jealous of those who write anything successful, but High Fidelity captured the loser/listmaker mentality so perfectly that all but the sourest of us were grudgingly reconciled to his genius.

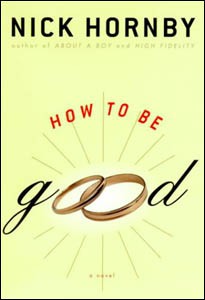

Hornby’s latest, How to Be Good, however, has little to do with rock or fandom. Instead, How to Be Good (Riverhead; $24.95) is about a female doctor’s failing marriage. Her husband, David, is a writer, and in this backstory lies the novel’s philosophic problem.

In addition to the inevitable failed novel, David writes a column for a local newspaper called “The Angriest Man in Holloway,” in which he rants about things that annoy him, including old people fumbling for their change in buses.

Hornby doesn’t say so, but I believe David is an intentionally distorted picture of rock critics and their snarky, pointless, jaded, and cynical view of life. In the book, David undergoes a metamorphosis, coming to hate his own cynicism and attempting to become “good” via various selfless but annoying gestures, such as inviting homeless people to live in his spare room.

Of course, these tactics fail miserably and ruin his marriage. Even more tragically, neither David nor the book ever really figures out a solution to his dilemma: How does one reconcile one’s critical–i.e., worse–self with one’s liberal, caring, and humane beliefs? Hornby doesn’t know the answer, but I admire him for exploring the question.

At some point, many critics recognize that their writing, their talent, their very point of view on life is, in the end, not a very admirable way to earn a living.

Sure, the world needs critics: without them, the arts (especially rock) would be in even a worse state, aesthetically, than they are. But being a critic creates a conflicted state in the critic. No one believes that our impulse to criticize stems not from hatred but from love, because it’s a lot easier to say something sucks than to say why it’s good. It makes for better reading–and writing. Hornby’s own work is a good example. Lately he’s been writing for The New Yorker, and his paeans to his favorite artists–Steely Dan, Lucinda Williams, and Radiohead–have been weak and unconvincing.

A more successful article, however, appears in the Aug. 20 issue, in which he analyzes the Billboard Top 10 for the week of July 28, including records by P. Diddy, Melissa Etheridge, Destiny’s Child, Blink 182, and D12. Hornby takes them down one by one, brilliantly and sensitively, especially D12, a side project of Eminem’s: “Ever since Elvis, it has been pop music’s job to challenge the mores of the older generation: our mistake was to imagine ourselves hipper and more tolerant than our parents. The liberal values of those who grew up in the 1960s and ’70s constitute an Achilles’ heel: we’re not big on guns, consumerist bragging, or misogyny, and that is the ground on which Eminem and his crew choose to fight. I know when I’m beaten; I can only offer sporting congratulations.”

The rest is just a flash of the angriest man in Holloway, without so much contempt. And probably to Hornby’s (or David’s) chagrin, the piece is both brilliant and a far better comment on the futility of criticism than How to Be Good.

Gina Arnold is a music journalist.

From the September 27-October 3, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.