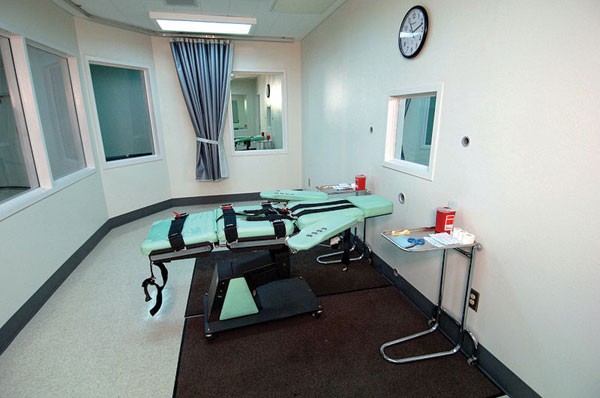

At San Quentin State Prison, 724 inmates are housed in the largest death row in the United States, waiting their turn on the lethal injection gurney. But if the Savings, Accountability and Full Enforcement for California Act (SAFE) passes on Nov. 6, their fate will change dramatically. On the ballot as Proposition 34, the initiative would abolish the death penalty in the state of California and replace it with life in prison with no chance of parole. If the proposition passes, California will become the 19th state to eliminate the death penalty.

Proposition 34’s foundation is built on a 2011 study by Judge Arthur L. Alarcón and Loyola Law School professor Paula Mitchell; their findings revealed capital punishment to be cost-heavy with few benefits. According to the study, ever since a successful 1978 campaign to reinstate the death penalty, California has spent roughly $4 billion and carried out only 13 executions. This breaks down to $184 million a year spent on trials and investigations, death row housing, and both state and federal appeals. Most death row inmates wait more than 20 years to see their cases resolved.

High-profile members of the SAFE California Act coalition include Ron Briggs, the man who wrote the 1978 Briggs Initiative, which reinstated and toughened the death penalty. Thirty-four years later, the El Dorado County supervisor has changed his mind. In a February 2012 Los Angeles Times editorial, Briggs admitted, “The only people benefiting today are the lawyers who handle expensive appeals and the criminals who are able to keep their cases alive interminably.”

Jeanne Woodford, executive director of Death Penalty Focus and a former San Quentin warden who oversaw four executions during her 1994–2004 term, is a major force behind Proposition 34. Woodford says she opposes the death penalty because it’s expensive, depleting resources at a time when the money is desperately needed elsewhere.

“We have a system that is broken beyond belief,” she says by phone, “one that continues to waste criminal-justice dollars at a time when people are laying off police officers and evidence is not being processed as it should.”

Proposition 34 would allow for the establishment of a $100 million fund to help law enforcement agencies solve rape and homicide cases, says Woodford. Further, the proposition mandates that convicted killers work during their imprisonment, paying restitution into a victim’s compensation fund.

[page]

The possible innocence of the convicted is also of concern. “The issue of innocence is really foremost in people’s minds,” says Woodford, citing the cases of Franky Carrillo and Obie Anthony, two men who turned out to be innocent after lengthy prison sentences. “More and more people have been exonerated across the country. There’s no coming back from the death penalty, and people are greatly concerned about that.”

By July 12, funding for the campaign reached $2.9 million, propelled by significant donations from Netflix CEO Reed Hastings and the ACLU. Opponents of the proposition, like the Peace Officers Research Association and the Sacramento County Deputy Sheriffs’ Association, have raised less than $45,000.

“There are some crimes—like murder, torture and raping and murdering children—for which a lesser punishment is simply not appropriate,” says Kent Scheidegger of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, which is against the ballot initiative but cannot afford to fund an opposition campaign. “It would be a travesty if someone like the Night Stalker [Richard Ramirez] got to live out his natural life in prison.”

Another opponent—one that may seem surprising—is death row inmate Kevin Cooper. Cooper was sentenced to death in 1985 for the murder of a Chino Hills family of four. Cooper and his advocates insist on his innocence, but in an essay written from San Quentin, Cooper announced that he does not support the SAFE California Act, citing frustration that no death row inmates were asked their opinion on the initiative.

Cooper argues that a life sentence in a prison with “inhumane conditions” is simply another version of the death penalty. He further claims that those currently on death row will lose their ability to use the appeal process and legal habeas for case review.

Woodford has read Cooper’s essay and sees flaws in his argument.

“The initiative does three simple things. It does not expand or shrink the kinds of crimes that are eligible for special circumstances,” she says, adding that many inmates are already required to work and pay into a victim’s restitution fund. “It just takes existing law and crosses out death penalty. It’s a very simple initiative. It does nothing more than that.”