We’re at the end of the tour, and nobody has the key to get into the lethal-injection chamber. That seems a little ironic in the moment. It has been a long day at San Quentin State Prison for reporters and corrections staff alike. The four-hour media tour of the death row facilities has gone on for six hours, and along the way, all day, there have been skeleton-type keys opening big metal-and-concrete doors, numerous ID checks, sign-ins and sign-outs at the three facilities that house the nation’s largest population of the condemned.

And now here we are, about 20 members of the media and a handful of San Quentin prison officials, including warden Ronald Davis, milling around outside the door to the never-used lethal-injection chamber. Waiting.

Lt. Samuel Robinson is the chief public information officer at San Quentin and has been our lead guide for the tour. Robinson says he worked on death row for 10 years before moving into his public-affairs role, and throughout the day he is greeted by inmates, a couple fist-bumping him as we make our way to and through the three areas that house the condemned: the Adjustment Center, the North Segregation Unit and the East Block, whose 520 beds house the majority of death row inmates at San Quentin.

“They live in a world,” Robinson tells reporters that morning, as he searches for the words, “an alternate world, the era when they left the streets . . . it freezes them in limbo.”

While we wait for the missing key to arrive, Robinson talks about how he was the corrections officer who handed off the last three condemned inmates to the team of officers charged with putting them to death.

Robinson’s last words to the inmates were always the same. “I wished them good luck.” He defers on the question of his personal feelings about capital punishment. As a state worker, Robinson’s not going there. He wished them good luck, that’s all.

And so it was that on Dec. 13, 2005, Crips co-founder Stanley “Tookie” Williams (who had been nominated five times for a Nobel Peace Prize and once for a Nobel Prize in literature) was executed. Triple-murderer Clarence Ray Allen was next; his luck, and his appeals, ran out on Jan. 17, 2006.

A month later, Michael Morales was given the same send-off by Robinson and was scheduled to be put to death at 7:30pm on Feb. 21. Two hours before he was to be killed by lethal injection, federal judge Jeremy Fogel put a halt to the execution after court-appointed physicians refused to inject Morales with a lethal dose of intravenous barbiturates. It will be 10 years in February since Morales lucked out, and 10 years since anybody has been executed at San Quentin.

San Quentin is a place of many contrasts, and one of the more starkly poignant examples I encounter on the Dec. 27 tour is the difference between how you access the death row facilities and how you access the lethal-injection chamber. It provides a handy metaphor for the status of capital punishment in California.

Gaining access to the condemned men in their cells requires reporters to pass through a set of security gates, sally ports and various other clearances, ID checks and metal detectors. It takes a while, just as it takes a while—25 years, on average—from the time an inmate is convicted to when he is executed, leading to a broken capital punishment system that, in 2014, federal judge Cormac Carney said was effectively a “life sentence with the remote possibility of death,” as he declared the California capital punishment regime cruel and unusual because of the delays.

That ruling was vacated by the U.S Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco in November on technical grounds—even as it did not rule on the constitutional issue raised by Carney. Another hurdle, another gate to pass through before anyone is executed here.

A proposed 2016 ballot initiative would recognize these costly and interminable delays that characterize the system, and end capital punishment outright. A similar ballot measure, Proposition 34, was beaten back by death-penalty advocates in 2012 by 52 to 48 percent.

And yet to gain access to the lethal-injection chamber, they just open an innocuous-looking door that faces out to the pleasant San Quentin grounds, steps away from the employee canteen and just a few yards from the heavy-security main entrance—and you’re in, just like that. A pro–death penalty referendum also scheduled for 2016 seeks to expedite the appeals process to get the executions flowing again.

Meanwhile, 724 men (and counting) sit on death row at San Quentin. There are between 12 and 16 whose last appeals have been exhausted, says Robinson, but there’s no time frame for the resumption of executions. “The if is the question.”

[page]

ATTITUDE ADJUSTMENT

The order is for murder

And we’ve been there before

The men in black are coming back

To serve the killing floor

—Lemmy Kilmister

One minute you’re listening to Motörhead records and mourning Lemmy Kilmister’s death while you dance around, a free man in your kitchen, and the next, you’re standing in the harshly appointed and zoo-like yard of San Quentin’s Orwellian named Adjustment Center, a 102-cell facility built in 1960, the solitary-confinement tier and most restrictive housing in the prison—and possibly the state.

The “A/C” is home to the worst of the worst offenders, not all of them condemned, though most, about 80 percent, are. It’s a self-contained prison within a prison, and the guards aren’t even allowed out once they check in for their shifts. It’s the deepest hole you can find yourself in at San Quentin.

This is the first stop on the tour, and it’s immediately apparent that we’re going to need more of those green anti-stab jackets; there just aren’t enough for all the reporters and cameramen, so some from other tiers are collected and made available as we squeeze into an Adjustment Center hallway and jostle our way forward to the gate.

The reporters can’t all go on the tier at once, so we proceed in shifts through a metal gate, having already passed through two other gates, and that’s not even talking about the first three gates we went through at the outset of the tour. Anyone who isn’t already wearing eyeglasses has to wear a face-protection mask to guard against any bodily excretions flung our way by inmates; we all wear the protective gear until we check out of the prison with our invisible “Get Out of Jail Free” wrist-stamps, as Robinson calls them.

No media person has seen the inside of one of these solitary-confinement cells in over a decade. A few of the cells are empty, doors swung open, and the officers let me step up to the entrance and enter a foot or so into the cells, keeping a watchful look or, one might say, glare. There’s an austere and off-putting peaceful feel to the tier that belies the daily dangers and stresses on both guards and prisoners alike; a creepy, treacherous monasticism prevails on this insular tier. That can change in an instant.

These men here are forever in a routinized and highly choreographed shuffle from one cage to another, and some are “indefinitely in leg restraints” as they are transported from cage to cage, Robinson says.

Two adjoining cells give a sense of the kind of privileges one can earn, whether an inmate is on death row or serving out a lighter sentence elsewhere in San Quentin, whose population hovers around 3,700.

There are two kinds of prisoners that transcend the Level 1 to Level 4 classification system (the Adjustment Center is Level 4), Robinson explains. There’s Grade A and Grade B. Grade A follows the rules; Grade B doesn’t.

One cell has a TV and walls filled with thong-wearing Latina pinups, while the next one over is absent any visible personalized touches beyond rolled-up white socks and a manila folder or two. According to online prisoner resources, death row inmates went on hunger strike here in 2013 in order, among other things, to get the same privileges the state affords the non-condemned. Robinson says that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation gives equal access to earned privileges, regardless of one’s classification.

But nobody in San Quentin is streaming Netflix, don’t worry about it. The TVs are hooked into antennas and reception is limited to network television. Inmates can also listen to the radio.

This morning, there’s only one inmate in his cell willing to talk to reporters, and it’s Sunset Strip killer Douglas Clark, described by Robinson as a “prolific serial killer,” who was associated with Carol Bundy and was rumored to be pals with her relative, Ted. Clark’s capital crimes were rather heinous and involved a beheading, but “Sunset Strip killer” does have a sexy anti-celebrity ring to it, and Clark does his part.

Clark says he has been in solitary confinement for 33 years and that “this is actually the best facility that they have.” Nobody visits him, Clark says, as he makes the best of what may be his greatest anti-celebrity moment of infamy since his incarceration.

Clark talks to reporters through a small vent in the closed-front cell door. Reporters press their mics against the vent and shout questions at the inmate, who shouts right back. He wears a straw hat and gives great quotage to the line of media waiting their turn. “You’re a reporter’s dream,” one reporter tells him. Clark says he loves the Sacramento Bee—but the guards? Standard issue: they’re corrupt, “a bunch of fucking morons.”

Inmates spend all their time in these cells except for three and a half hours of yard time three days a week. One of the other whopping contrasts immediately evident is that San Quentin is really two prisons; its general population is among the least violent in the California prison system, even as it houses the most violent offenders in the state.

It’s a prison that benefits mightily from a generally empathic Bay Area demographic with a volunteer cadre of 4,000 people who provide all kinds of programming, and Davis says the programs are what keep the violence in check.

And while San Quentin is famous for its Shakespeare productions and other reform-minded efforts at rehabilitation, little of that is available to the condemned. About a hundred of the condemned have access to hobby and craft programs, but that’s about it as far as programming goes, Robinson says.

There are no restorative-justice programs for the condemned, either, no opportunities for inmates to meet with survivors of their mayhem, Davis says, because of security issues around inmate-civilian contact, a key aspect of restorative justice.

The contrast between general population and the condemned plays out in the functioning and upkeep of death row itself. Prison labor built the new $850,000 lethal-injection chamber, and prisoners are also at work on a project to retrofit cells in San Quentin’s Donner building to expand death row capacity by 97 beds. That unit will open this month or next, Robinson says.

As we stand in the Adjustment Center, Robinson tells me about another inmate here whose penchant for violence ended the career of four corrections officers. We’ll meet him soon enough.

[page]

We leave the tier and wait in another sally port before gaining access to the Adjustment Center yard, which consists of a couple dozen single-man “walk-alone” cages with sinks and toilets, and one larger yard for inmates who have mingling privileges. There’s only one inmate in there today, one of about 10 men out here this morning in the cold rows of cages—pacing, talking among themselves, doing pull-ups, mostly in white shorts and sneakers, though a couple wear prison-issued sweats. It’s a little chilly out here.

The protocol is a little unclear, so I set off into the wilderness of cages and approach a very large and shirtless Latino man. He asks me what we’re doing here, what’s going on. He looks like he could crush my skull with the power of his nipples alone.

I tell him it’s a media tour of death row and that I want to interview him—but I’ve apparently gone a little off the reservation, as an officer tells me to get back with the rest of the reporters, who have gathered around another cage.

“They’re censoring you!” the man shouts after me as I rejoin the group—then subsequently passes on the opportunity to sign a required consent form to talk with reporters. A little while later, Robinson tells me that was the very inmate who ended those corrections’ officers careers. He seemed so friendly for a second there.

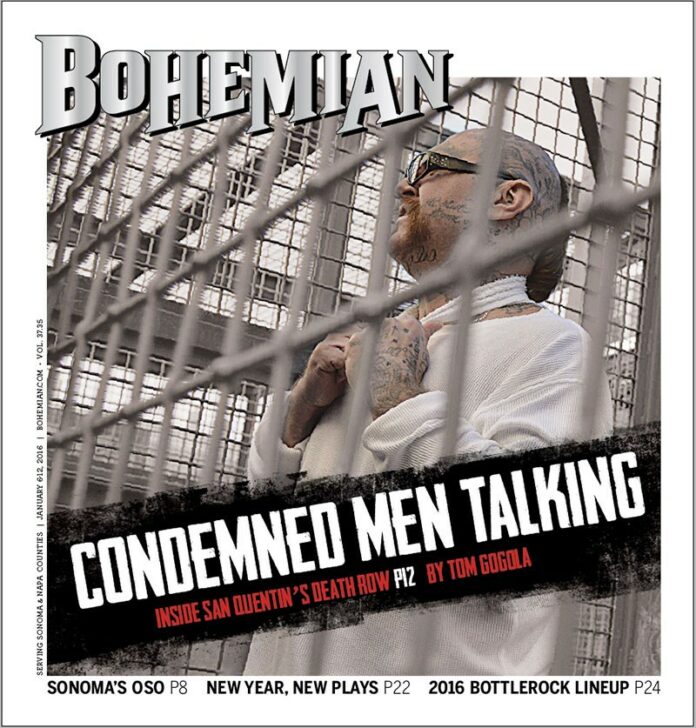

Reporters are gathered around the cage that houses Robert Galvan, a seriously bad man, and it’s hard to suppress the thought that Galvan has a little bit of the Lemmy look to him. “I deserve to be here,” Galvan says as he talks about life on the Adjustment Center tiers, where there is “absolutely zero privacy.”

Galvan has a general mien of biting, accessible menace, and I ask him what it feels like to be on death row in a state that almost never executes anyone. “It’s like being left on a shelf,” he says. “I feel like that’s torture.”

The book on Galvan is that he had so many “assault with a deadly weapon” charges, including one for assaulting a corrections officers, that prosecutors stopped pursuing them after stringing together three consecutive life terms. His capital crime occurred while he was already locked up: Galvan killed his cellmate.

The pro–death penalty referendum on the docks for 2016 seeks to end the practice of housing the condemned in one-man cells, to save money. California spends almost $200 million a year in costs associated with its stalled capital punishment regime.

How’s the food, I ask, and Galvan laughs a short, hard laugh. “It’s food.” He says they don’t serve that notorious “Nutraloaf” at San Quentin, where the biggest food gripe I hear through the day centers around the ready availability of pancakes.

Galvan says, “That’d be a good if they did it,” when asked about the 2016 referendum to end capital punishment, but he’s never getting out of here, death penalty or no death penalty: “It’ll be the same thing, a different cell, different atmosphere, but I’m still in a cell 23 hours a day.”

JARVIS JAY MASTERS

Inmates . . . can assume the role of monk or gladiator, and the duality between prison warrior and prison monk is particularly true on death row.

—Jenny Phillips, reviewing That Bird Has My Wings

Disembodied voices, harsh and angry and demanding, greet reporters as we spilled into the vast East Block, home to the majority of the 724 condemned of San Quentin. There are more than 500 men here, and they shout down from the upper tiers, “They got us in restraints like we are animals!” “We want to come out of the handcuffs!”

They shout about the spoiled milk and the endless pancakes and they shout about Burton Abbott, exonerated but nevertheless executed in 1955, from this intensely intimidating, five-tier stack of cells. American flags hang from sky-high rafters in both wings of East Block, and guards walk the gangway as reporters are set loose on the tier to find inmates to interview. We walk past naked old men in showers, a guy sitting on the crapper and a couple of telephones-on-carts that are rolled in front of the cells for inmates’ use.

I walk down the tier and stop in front of the one inmate I had hoped to encounter today, and offer greetings to Jarvis Jay Masters, the Buddhist author of 2009’s That Bird Has My Wings. It’s a heavy story about Masters’ upbringing and his path to death row, with harrowing-funny stories about the violence of life among the condemned and Masters’ journey to a monklike and meditative existence on death row.

Masters had just recently ended a 27-day hunger strike prompted, he says, by a chronic absence of capital-crime lawyers at the prison. He ended up weakened and ill and on an IV at Marin General Hospital, and only ended the hunger strike when the warden came to see him.

“Guys are dying and nobody is up here saying, ‘You are a human being,’ Masters says. “Nobody says, ‘Tell me your story.’ The lawyers don’t even know their clients’ names, their stories, their suffering. It felt like there was a purpose behind the hunger strike. It helped me to understand suffering.”

[page]

Masters is at work on his third book (he also published Finding Freedom, a collection of prison writings, in 1997). This one is going to be called Out of Bounds, a fictionalized retelling of his early-1970s childhood, he says, that will explore the abuse and molestation he says he experienced as a youth. “Out of Bounds” is the single most prevalent stenciled signage on the walls of San Quentin. The signs inform inmates that they’ve entered a restricted area.

Masters, a native of Long Beach, covered a lot of biographical ground in That Bird Has My Wings, which told the story of his rough upbringing, his four siblings parceled out to foster homes, him getting shuffled from a nurturing foster-care environment to another that was full of violence and abuse. All of which led to his life of violent crime as a young man.

Masters spent 21 years in the Adjustment Center, and turned to Buddhism and meditation to help survive the intense psychological strain of long-term solitary confinement. He has a dedicated support network on the outside that includes renowned Buddhist author Pema Chödrön, and a legal team at work to get his conviction overturned. Masters says Chödrön understood why he had undertaken the hunger strike, though she did not support his decision.

Some inmates, Masters says, have come to a kind of peace on death row; they’ve outgrown their criminality, but it can leave them in an awful and hopeless limbo. “Some people have made the transition,” he says, “but there are more suicides than executions here.”

Masters’ Buddhist practice and meditation have kept him grounded in the face of a death sentence handed down after he was implicated in the 1985 murder of prison sergeant Howell Burchfield. “Spiritual grounding is a real, real, enduring force if you ever find yourself in a situation like this,” Masters says.

There are all kinds of ways to torture yourself on death row, he says, which include dwelling on “the contradictions in your life, the callings that you will think about for the rest of your life.” Whether an inmate is innocent or guilty, “death row means you are in a lot of trouble, and you sit with that—my writing, that is how and where I found my greatest reflection of that fact.”

Masters was sent to San Quentin in the early 1980s to serve a 10-year armed robbery sentence and then joined a prison gang. A few years into his term, he was implicated in the death of Burchfield and charged with sharpening a piece of bed frame into a shank, which was then fashioned into a spear, using rolled-up paper. Two other inmates were given life sentences without parole for their role in the murder; Masters got the death penalty.

There’s a website called the Officer Down Memorial Page (odmp.org) that honors law enforcement officers killed in the line of duty. The entry for Burchfield contains a quote from Euripides that has a particular potency when it comes to Masters, who has maintained his innocence all along: “When a good man is hurt, all who would be called good must suffer with him.”

I ask him about his writing process, and Masters enthusiastically pulls out a white five-gallon bucket from the back of his cell. That’s his writing chair. A large board propped on his rack serves as his desk. Then he shows me his pen.

When he was in the Adjustment Center, Masters’ writing implement consisted of a floppy pen tube sans its plastic outer shell. He’s been in the East Block since 2007 and takes apart the pen and shows me how it used to be. He gets a regular pen here.

In San Quentin, and especially on death row, the smallest of details and items, which in the outside world would be considered trivial and mundane, can take on a new kind of value and force. Masters laughs as he shows me the other key piece of his writing kit, a tan crocheted hat. “Don’t tell anyone, but I need my writing hat. I can’t write without it.”

Masters’ many supporters are adamant that he is innocent of the capital charge that landed him on death row, and with a little bit of luck—and a positive ruling from the California State Supreme Court—he may find himself in a whole new situation by the end of February.

In the meantime, there’s a lot of old-fashioned Buddhist non-attachment that has to be brought to bear on the outcome. On Nov. 15, the court heard oral arguments from his defense team and from prosecutors.

“The case is still alive,” Masters says, and the clock is ticking on the court’s 90-day window to issue a ruling. He could be looking at a new trial, or more of the same. Either way, he’s ready. “Life changes one way or the other,” Masters says. “One thing I have to do is be in the center; that’s where my practice is. Being in the cell, it is so small and you get pulled—it is scary. You feel you are being pulled one way and then you are pulled the other way—the fear of wanting to stay in, the fear to get out—and so it is just so powerful to stay in the center.”

His hunger strike ended when Davis came to him in the hospital, Masters says, “and pointed some things out to me. I felt blessed. He allowed me to take a step back when he said, ‘You made your reason known.'”

But he couldn’t bring himself to eat the prison food after. “I couldn’t eat none of it,” he says with a laugh. “I stared at all that food, looked at it and touched it. But I couldn’t eat it.”

We talk about the the idea that you “always want to leave a little bit on the plate,” as a gesture, perhaps, of gratitude and solidarity with the suffering—or to simply indicate that you are full. He says of his hunger strike, “You are doing it for somebody, and you got something out of it, too. It was about awareness, not making a demand.”

Masters is 52 years old and says one of the great challenges for any death row inmate is to acknowledge one’s misdeeds while also leaving open the possibility for a kind of deliverance via personal growth.

In his 35 years at San Quentin, he says the enormous challenge for inmates is to acknowledge “that you can be a better person. There’s regret and there’s growth. These are the circumstances we all have to deal with, one way or the other. You can have the regret, but also the determination to not give in. You damage a lot of people when you do robberies, and I cried like a baby when I got here. The only thing you can do is sit with it, and say, ‘We are real human beings.'”

[page]

THE ANTI-CELEBRITY

To the extent that it’s possible, I like to live by a professional code where I’ll chase a fact, but I won’t chase a celebrity. That includes chasing anti-celebrities on death row, like Scott Peterson.

The last full-on media tour of San Quentin’s death row, Robinson says, was given around the time Peterson was in the news as international anti-celebrity du jour. Interest was high. Peterson was universally reviled for killing his eight-months-pregnant wife and saying he was on a fishing trip in San Francisco Bay.

The TV cameras haven’t been in here since Peterson’s conviction, but San Francisco KALW radio reporter and author Nancy Mullane was given access to death row for a series of reports she produced between 2012 and 2014, and which culminated in a book, Life After Murder, which wasn’t about death row, but about five inmates who Mullane believed deserved a chance at parole.

When Mullane’s book came out, she was invited on The Today Show, co-hosted by Matt Lauer. The interview was frankly one of the most revolting exercises in the media’s anti-celebrity obsession you will ever witness. Lauer took the implied bait that Peterson was living a cushy life on the North Seg unit, the least-restrictive of the three death row facilities at San Quentin: He has his own cell! Reportedly allowed to spend up to five hours a day outside of it!

What’s clear from the segment is that Mullane would never have been invited on The Today Show had she not inadvertently captured Peterson in some photos she took on the North Seg rooftop yard. She didn’t even know it was Peterson she was shooting until after the fact. One of the photos found Peterson smiling and shirtless, playing basketball.

The five inmates that were the subject of Mullane’s extremely worthwhile book were rendered an afterthought by Lauer: “We want to talk about them in just a second,” but please first tell our viewers how you never even talked to Scott Peterson, that’s fascinating.

We are up on the North Seg rooftop yard and, wouldn’t you know it, there’s Peterson with his back turned to reporters. We’ve interrupted a basketball game. He and another man, an African-American of less anti-celebrity stature, stand that way the whole time reporters interview other inmates.

The condemned of North Seg are granted tier time to mingle with inmates, and they can spend about six hours a day, from 7:30am to 1pm, in the rooftop yard, with its stunning views of San Francisco.

There’s sheet-metal fencing around the yard, which Davis says is there mostly to protect the privacy of inmates from binocular-wielding gawkers—another of the many contrasts within San Quentin, where there’s no privacy among and within the condemned but there’s an effort to shield them from the eyes of a prying public.

This anti-celebrity dynamic is in the air all day long, and we all play into it a little. There is a peculiar thrill to being so close to the condemned, especially when some of them are so totally irredeemable, and any journalist will tell you that a chance to visit death row, San Quentin—that’s reportorial gold. But the anti-celebrity media scrum did feel a little unseemly.

That morning, outside the main entrance gate to San Quentin, as reporters waited to be let into the prison, the chatter was all about Richard Ramirez, who is dead, and Charles Manson, who isn’t even on death row. I sat there with a cocked ear and recalled an interview I did many years ago with the writer Ed Sanders in his upstate New York home. Sanders wrote a book about the Manson murders, The Family, and I always remembered his quip about the relationship that sprung up between the men: “You haven’t lived until you’ve gotten a Christmas card from Charles Manson.”

Serial killers occupy a peculiar social strata in the American imagination, as do upstanding white people like Scott Peterson who commit heinous crimes—it’s the last thing you’d expect of them. So Peterson turned his back, but Steven Livaditis availed himself to reporters on the rooftop yard. Livaditis killed three people during a 1986 jewelry store robbery in Beverly Hills and almost immediately admitted to his crime and found solace in the Bible. He’s been in the North Seg unit for almost 30 years.

Livaditis is a long, long way from his Bay Ridge, Brooklyn roots, and while he says that “it seems pointless to have a death penalty when people are not being executed,” he believes that some criminals deserve the capital charge, including Polly Klass’ killer, Richard Allen Davis, who also turned his back to reporters from his East Block cell. “In some cases the death penalty is appropriate,” Livaditis says.

Yours?

“It does merit capital punishment.”

Livaditis says his death row days consist of reading the Bible and trying to “live the life of a good Christian. I have tried to make amends with the families,” he says. Does God want you here? “Good question.”

Livaditis is asked what a condemned, born-again man can do to help others, and he states simply that he has “a Christian responsibility to help as many people as possible.”

[page]

BIG PRODUCTION

The tour is a big production for the prison, and there are many moving parts both at San Quentin and around the politics of capital punishment that would indicate one was in order. Beyond the expansion of its death-row facilities, the prison just passed the one-year anniversary, in October, of the opening of the court-mandated and first-in-the-nation Psychiatric Inpatient Program (PIP) for condemned inmate patients, which reporters get to tour as well.

The 40-bed facility was built at a cost of $620,000 to address a stark reality that numerous men have been driven completely insane during their decades of limbo on death row. Veteran reporters recollect tales of harrowing, incessant screams on the East Block, which drove a federal order to build the PIP.

Our prison guides show us the inside of the group-therapy rooms that comprise part of the treatment, and once again, wherever the condemned of San Quentin go, whatever their mental-health status, they are held in cages. Dr. Paul Burton, who oversees the unit, says he’s fairly certain that taking photos of those units is off-limits, even though there are no inmates in the room. The cages are small holding cells with a steel stool in them.

This unit feels peaceful in much the same way the Adjustment Center has an eerie sense of calm about it. One inmate stands at a big window looking out with his hands behind his back. The rooms are larger here, and there’s a dictionary and a board game or two on a shelf in the room.

The other moving part: The state recently announced its new single-drug execution protocol that calls for a lethal dose of barbiturate to be administered to the condemned, amid a national focus on lethal injections that have gone awry because of multi-drug cocktails, and questions about the medical ethics of killing the condemned.

The state is getting its death-house in order for whatever might come next, while tacitly acknowledging that it was extremely bad form for the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to allow one reporter, Nancy Mullane, exclusive access to the largest death row in the nation, while telling other reporters that they can’t tour the facility because of the dangers.

And so here we are, near the end of the tour. It’s been quite a day so far.

THE BENT, RUSTY NAIL

It took me about two full days to decompress from the tour, and when someone would ask, “How was death row,” I couldn’t answer the question; I had no idea what to say. When I got home later that night, I just stared off into space awhile, and my mind kept coming back to this one moment.

Jarvis Masters’ pen demonstrated to me how very small details and privileges take on amplified significance in the land of the condemned, where human dignity and mercy are stretched to their limit, and where the threat of violence is real and imminent—prisoners with nothing but time on their hands on constant lookout for that tiny crack in security, that opportunity to commit violence, to exploit an opportunity.

I couldn’t stop thinking about a bent, rusty nail that I saw on a landing in the North Seg yard. To get to that unit, reporters followed Robinson up six flights of circular stairs to the rooftop yard, and as we filed back onto the landing, I looked down and spotted the nail just sitting there on the ground. If you looked up, there was Mt. Tamalpais.

I thought for a second that I should pick up this nail and ask the warden about it, but there was no way I was going to do that. That nail represented murder. And yet I had to admit later that there is something about San Quentin and an encounter like this that stimulates one’s inner deviant; it’s just a fact of life. Later, I thought about a journey that the nail could have taken, and this is exactly why the state does background security checks on anyone who wants to visit death row. They don’t want nutbags picking up random nails and passing them off to prisoners, for one thing.

Drop my notebook, tie my shoe, pick up the nail. Would’ve been a snap. We left North Seg and headed to the hospital, and then the East Block. That nail was a weapon, a lethal weapon, a ticket to mayhem. In any other context, it’s just a nail. Here, there is vast and unlocked potential for evil.

I should be clear here in saying that this landing, and this area of the prison, is one that no inmates have access to, condemned or otherwise. But we passed through the outdoors general population on our way to a tour of the PIP wing, and then we went to the East Block. There were numerous opportunities when one could have passed that nail to an inmate.

THE END IS NEAR

We’re almost at the end of the tour and I linger with a couple other reporters at the other end of the East Block, where along one wall are the rows of tiers, and along the other, small holding cells for inmates returning from the law library or elsewhere. It feels like we’re trapped between these sets of cells. There’s no place to lean back and take it all in, and that’s a little unsettling, especially when I back into one of the holding cells and hear a “Hey,” come from it. There’s a man in there with a manila envelope and a goatee, and I wonder if he could have made use of that nail. Scary.

We’re waiting for the rest of the reporters to finish interviews, and a couple of other inmates are brought onto the tier and placed in the holding cells. They put their arms through a slot in the ritual removal of the handcuffs and one of them asks the goateed man about an empty cell across from them.

“He cut himself last night.”

Damn. They open the gate and we are, surprisingly, right back where we started, at the main entrance to the prison. We pile up the anti-stab jackets on a table, throw away the face protectors, show our ID a couple more times and file outside for the last stop on the tour.

ENTER THE SEPULCHRAL

The key has arrived and they open the door, and just like that, we’re in there, the state’s new, as-yet-untested lethal-injection facility. It’s a bare, two-room chamber, save for 12 chairs and a gurney containing numerous black straps. A big clear window separates the chairs from the gurney. This is the only part of the tour where cameras are banned, as though we’re going to steal a soul by taking a photo of the death-gurney.

All the reporters and TV guys have to leave their cameras on the ground outside. I can’t say enough about how weird it is that they just open a door and you’re in the chamber.

And again I found myself taken by how a facility with such heavy violence associated with it can have such a strangely peaceful and sepulchral elegance to it, this clean, austere chamber of death, deliverer of the haunted and broken and malevolent. The gurney arms are splayed in a Christ-like manner, and let’s not forget that he was the man, after all, who died a criminal’s death despite his innocence. For what that is worth.