Dylan Revisited

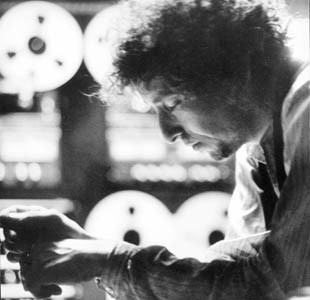

At 60, Bob Dylan remains unstoppable

By Stephen Kessler

“NEVER MAKE your muse your mistress,” the poet Kirby Doyle once counseled me. He meant, I’ve since learned, that when the one whose soul most closely rhymes with your own is near at hand, inspiring as her presence might be, that’s nothing compared to the way her absence can move the imagination. As anyone knows who’s ever written a love letter, distance amplifies inspiration. This is one of the cruelest paradoxes of creativity: the experience that comes closest to destroying you–say, the loss of your lover–is often the one that transports your art to its greatest depths and heights. Your loss proves, perversely, to be your gain.

Given the choice, it’s a twist of fate not everyone would bargain for.

When Bob Dylan’s marriage was breaking apart in the mid-1970s, that devastating event occasioned one of his greatest albums, 1975’s Blood on the Tracks, an artistic turning point. It would be stupid to assume that anything Dylan has written is strictly autobiographical–he is, after all, the most elusive and unreliable of narrators, and even as heartfelt a work as that one is full of richly ambiguous invention. But the missing muse of his most recent disillusioned love songs bears an archetypal resemblance to the real-life mate he was losing back then. Just as the albums he recorded in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when he was settling down and starting a family–earlier records like John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline, New Morning, Planet Waves, and even parts of Blonde on Blonde–contain some of the lightest, happiest sounds he’s ever made, the songs and albums since then have turned increasingly darker, heavier, and more desperate.

Having listened pretty closely to most of his work for nearly 40 years, my intuitive sense is that only one person could have caused the pain he has chronicled recurrently over the last decade. It sounds to me like the same “shooting star” who left him tangled up in blue more than 25 years ago. Ex-wife Sara? Perhaps. Not that it really matters; the songs themselves have an independent existence. But only a loss of enormous proportions could inspire such consistently compelling and miserable yet somehow triumphant art. The indestructible minstrel–who turns 60 on May 24–appears to have taken his personal tragedy and wrung its neck.

Not that he’s ever had any shortage of girlfriends–before, during, or after his legendary marriage. As reported in Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan (Grove Press), a new biography by Howard Sounes, the singer’s personal magnetism has always been irresistible to women, and his desire for female companionship insatiable. A map of his love life would look like a Jackson Pollock painting. Yet there remains, in most of his music of the past 10 years or so, that nagging note of desolation, if not outright despair. How he turns such bitter feelings into such extraordinary songs is a mystery, but there are clues for the attentive listener.

The philosophical instrument of this transformation is a deadly dark, no-nonsense irony. Even, or maybe especially, at his most gloomy, Dylan is funnier than most comedians. The black comedy of his best writing–abundantly evident in “Things Have Changed,” his rocking, Oscar-winning dirge from Wonder Boys–manages to twist the grimmest revelations of woe and hopelessness (“Standin’ on the gallows with my head in the noose”) into a perverse form of affirmation. “All the truth in the world” may, as the singer grumbles, add up to “one big lie,” but the recognition of this hard-to-stomach fact is curiously consoling when set to a biting lyric, a catchy tune, and a driving beat that makes you feel like dancing.

Just as the musical beauty and imaginative richness of such classic bad trips as “Desolation Row” and “Visions of Johanna” somehow transcend the creepiness of what they depict, so “Things Have Changed” and most of the songs on the much-acclaimed 1997 album Time out of Mind both sink the heart and lift it at the same time.

AGED as he obviously is–Dylan’s latest face revealing the ravages of four decades of practically nonstop traveling–it’s still not easy to believe he can be that old. That he’s managed to last this long is an accomplishment not even an astrologer could explain. His astonishing rise in the early 1960s from scruffy coffeehouse folksinger to international rock-and-roll demigod between the ages of 19 and 25; the mysterious motorcycle spill that turned him into a phantom for a while; his tireless touring; his two (yes, two) divorces; tobacco and drug and alcohol abuse; relentless harassment by deranged fans; legal struggles with various managers and execs and associates; an exotic cardiac infection that could have killed him; the grueling demands of a fame so monumental as to render him almost mythic–such an itinerary would be (and has been) enough to finish off many lesser mortals.

But Dylan is nothing if not tough. He has tenaciously persisted, through his whole roller-coaster career (people have written him off at various stages as a sellout, a crackpot, a crank, a has-been, and worse), in being unmistakably nobody but himself. He has, to paraphrase Faulkner’s Nobel speech, not only endured but prevailed.

Using a voice that began as a nasally rasp and has deepened over the years into a sort of gravelly wheeze seasoned with the fatalistic wisdom of a million cigarettes smoked all alone as the sun goes down, the man has improbably made himself into one of the most soulful singers since Billie Holiday. Like Lady Day, he seldom sings the same song the same way twice–changing arrangements, styles, rhythms, melodies, and even lyrics for the sake of keeping old material fresh–and through an uncanny sense of timing, phrasing, and intonation is able to convey feelings and insights most of us could hardly bear to face without such consummate artistic intervention.

Dylan has often said that he doesn’t really write his songs, he just kind of copies them down as dictated from some other source, most likely God. He has the musical instinct of a mockingbird, able to imitate and adapt for his own use practically anything he hears. He works on the fly and by ear–he neither reads nor writes music–often not even letting his backup musicians know in advance where a song is going. He’s a strong and distinctive pianist, as can be heard on any number of songs where the person pounding out those mournful chords could be no one else. He’s also an expressive if technically primitive harmonica player. A first-rate folk and blues guitarist since the beginning (his debut album in 1962, Bob Dylan, displayed a driven energy whose intensity still startles), his skills as a musician have only increased over 40 years of practice.

On the old-school blues and folk albums he recorded in the early 1990s, Good As I Been to You and World Gone Wrong–both loaded with traditional songs from diverse sources recounting classic tales of lust, deceit, betrayal, murder, and other unsettling revelations of human nature–Dylan, unaccompanied, revisits his roots with a ferocity that has grown more powerful and resonant with age. He seems to be channeling ancient spirits as he takes the material and makes it, through the forceful personal truth of his playing and singing, both timeless and up to the minute.

That same connection with ancient forces has always suffused his original songs with a sense of history, hard experience, and existential authority. My father, who had hustled his way into the upper middle class from the scrappy streets of Depression-era Seattle, was no fan of rock and roll, but one afternoon around 1967 when I was home from college he came into my room while I was playing Highway 61 Revisited (another contender for greatest Dylan album) and, after listening to a few verses of “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” declared, nodding toward the speakers, “He knows life.”

IT’S STRANGE the way you can reach at random into almost any period of Dylan’s far-ranging career and find a song that seems to have been around forever as part of our common patrimony. The artist embodies what T. S. Eliot was talking about in his essay on “Tradition and the Individual Talent”: a profound immersion in the canonical repertory that proves to be an endless source of originality. From biblical hymns to carnival music, bordello boogie-woogie to baby lullabies, Hank Williams to Little Richard, Odetta to Buddy Holly, Stephen Foster to John Lee Hooker, Mississippi John Hurt to Bill Monroe, Frank Sinatra to Robert Johnson, Elvis Presley to Woody Guthrie, Dylan’s deep knowledge of virtually every American folk and pop tradition gives him an unmatched breadth of creative resources that have never ceased to feed his genius.

The “protest” singer of the early 1960s who broke through the innocuous complacency of the Top 40 to become some kind of cultural prophet and “voice of his generation” outgrew that role in a hurry and has been fleeing it ever since. As Sounes documents in his well-researched book, Dylan was never especially political, even though he caught the spirit of the civil rights movement in a few iconic songs. If you listen to an album like The Times They Are a-Changin’ (1964), you find that the title song as well as others, like “When the Ship Comes In” and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” may have been timely at the time but are still right up to date and universal.

Later, even such a topical song as “Hurricane,” written explicitly to make a case for the exoneration of wrongly convicted boxer Rubin Carter, holds up because it’s such a well-wrought piece of musical journalism. The operative word is musical; it’s Dylan’s lyric gifts and commitment to music rather than social reform that give his “political” songs their lasting power.

As Allen Ginsberg astutely observed in one of his late poems, “Dylan is about the Individual against the whole of creation.” He often writes and sings as if to himself, giving his songs an inwardness that speaks to others at an intimate level; that’s why so many people feel they have a personal relationship with him.

Greil Marcus, another insightful Dylan commentator, noted in his book Invisible Republic that Dylan’s crime against the folkies when he “went electric” at Newport in 1965 was not so much just plugging in but, what was more radical, having the nerve to speak for himself as an individual artist rather than for the collective. His refusal to be a “spokesman” was and is a mark of his integrity. Leadership was the last thing he was looking for–except perhaps in a creative sense, always trying to stay several steps ahead of the competition.

The fact is, his nastiest, most spiteful songs, from “Like a Rolling Stone” to “Idiot Wind,” are equally if not more persuasive than those idealistic anthems that made him a poster boy for Justice.

And yet, true to his own contradictions, the man has always, even at his most surreal and nonsensical, remained some kind of moralist. In his search for spiritual truth he has found clear choices between right and wrong–or perhaps more accurately, between integrity and hypocrisy–or as yet another choice, between clarity and muddleheadedness, which can lead one to be deceived by worldly appearances.

When he was at his most self-righteous, during the period of his conversion to Christianity, his music remained unscathed despite its evangelical intent. Slow Train Coming and Shot of Love are among his most underrated albums. Easily the best of his four concerts that I’ve attended was the all-gospel show he and his troupe performed at the Warfield Theater in San Francisco in 1979. The band absolutely rocked in a way that, if you had faith or were looking for religion, might have put you over the top. If not, and if all you were listening for was a message, you might have found that concert extremely irritating. But Dylan has never been afraid to piss people off, and he’s often at his best when most obnoxious.

Nearly 20 years later, long after his Christian phase had fizzled, there was the interesting spectacle of Bob Dylan pimping for the pope by doing a gig at the Vatican, with the pontiff, after the performance, riffing in his sermon on “Blowin’ in the Wind” as a call for the world’s youth to embrace Catholicism. Surely that incident must have left even the most dedicated Dylanologists scratching their heads. My theory, more or less confirmed by Sounes in Down the Highway, is that Dylan did it for the money.

IN ANY CASE it’s been a long and twisted road from “Come gather ’round, people . . . the times they are a changin’ ” to “I used to care but things have changed.” The river connecting these very different psychic landscapes is change itself. (As the man says, “Lotta water under the bridge, lotta other stuff too.”) Change, and the pesky specter of paradox: “The first one now will later be last,” fair enough; but at a far more intimate and vexing level, “I’m in love with a woman that don’t even appeal to me.” Or, worse yet: “I’ve been tryin’ to get as far away from myself as I can.”

Such gallows-Zen double-whammies are what charge Dylan’s most recent work with its extraordinary philosophical zest despite its undeniably disturbing undercurrents. The bitter lucidity of a song like “Not Dark Yet” (on Time out of Mind) displays a bleak wisdom as bracing in its honesty, as beautiful and spookily exhilarating as anything he’s ever written.

The excellence of the music, as always, is instrumental in lifting the heaviness of both “Things Have Changed” and Time out of Mind into a transcendent sphere, but without their intellectual engagement with an Ecclesiastes-like “vanity of vanities,” the songs would never soar as they do. Dylan’s willingness to wrestle in public with his own suffering–what he has called “the dread realities of life”–his courage in revealing the depths of his inner journey, is what continues to set him apart from other pop-culture stars and in the process endear him to his listeners.

One of the most notable aspects of his evolution as he proceeds to endure his fate as a public figure is the apparent emergence of a true humility even as his stature grows. Anyone alive in the 1960s remembers the cocky rock star of Don’t Look Back, D. A. Pennebaker’s great documentary, where the 24-year-old Dylan is exposed as so arrogantly brilliant that he appears to enjoy shredding the psyche of any Mr. Jones insufficiently hip to dig what’s happening. Thirty-six years later he may still have no patience for fools, but he has learned to accept the official symptoms of respectability: the raft of honors and prizes, the Grammys, the Oscar, the Kennedy Center medal, and numerous other lifetime achievement awards.

Graciously receiving such accolades, the artist, by now a grandfather, seems almost abashed, embarrassed by his success and as grateful for the recognition as any other mortal would be. In his slightly uneasy pleasure as an object of mass love, Dylan reveals a winning insecurity and a deep humanity that only makes him more likable–especially after the unhappy endings that haunt so many of his songs.

Which brings us back to the blues, and that rhymes with muse. The lost lover, whether an actual person or an idealization of multiple romantic catastrophes, has implanted an ache in the singer’s soul that literally keeps him going (“It doesn’t matter where I go anymore, I just go”). The blues: bedrock of Bob Dylan’s musical road; hard but self-sustaining way of life; consolation for the wounds of love; safety valve for the inconsolable grief that might otherwise smother the spirit; lifter of the heart that refuses to concede defeat.

A lonesome death awaits us all, but meanwhile the poet writes, the composer composes, the musician plays, the singer sings, the entertainer tours. “I’m mortified to be on the stage,” he’s said, “but then again, it’s the only place where I’m happy.”

Stephen Kessler is a poet whose most recent book is ‘After Modigliani.’

He resides in Gualala.

From the May 10-16, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.