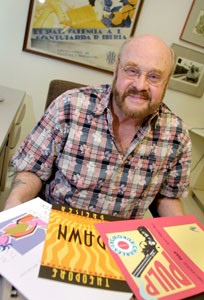

Photograph by Michael Amsler

A Flashing Heaven of Luck

Black Sparrow Press leaves a mighty legacy

By Geneviève Duboscq

It had to bite the dust sooner or later,” says John Martin, founder of Santa Rosa’s Black Sparrow Press. On July 1, Martin will close the doors on 36 years of independent literary publishing. “I mean, I’m 71 years old. I’ve been doing this since I was 35. That’s over half my life.”

Far from looking tired, Martin radiates energy, and he’s a born storyteller. With oval wire-framed glasses, bushy red-brown eyebrows and beard, and a bald spot up top, he could play Santa at a Christmas party. He’s wearing a short-sleeved button-down shirt with little blue palm trees marching across it, dark pants, and tennis shoes. A faded blue tattoo colors his right forearm.

“Black Sparrow is really considered, by English-reading people all over the world, to be one of the very best and most successful literary publishers in the world. . . . To have lasted 36 years and been profitable that whole time–I’m very proud of that, damn it.”

Martin was manager of a Southern California office supply company that did some printing when he read the work of writer Charles Bukowski in mimeographed magazines in 1965, and sought him out. Meeting over the next six months, the two men worked out a deal. Bukowski needed $100 a month in order to quit his post office job and work on the writing that was stacked waist-high in his closet. Martin gave up one-fifth of his monthly salary to sponsor Bukowski and become his publisher.

In an interview with Transit magazine before his death in 1994, Bukowski said, “Black Sparrow Press promised me $100 a month for life if I quit my job and tried to be a writer. Nobody else even knew I was alive. Why shouldn’t I be loyal forever? And now the royalties from Sparrow match or surpass all other royalties. What a flashing heaven of luck.”

A book collector since the age of 20, Martin sold his collection of D. H. Lawrence first editions for $50,000 to UC Santa Barbara, leaving $30,000 after taxes and fees to establish Black Sparrow Press. The first publication in April 1966 was 30 copies of Bukowski’s poem “True Story,” which Martin priced at $10 and mostly gave away. “I wasn’t trying to sell those. They’re worth a fortune now, like $2,000 or $3,000 apiece, and I would give them to my delivery boy at that office supply company or one of the secretaries.

“I thought, ‘Well, maybe I’ll do a little book.’ And then I did another little book and another little book, and I did other people’s books.” Martin regularly worked 16-hour days: eight hours at the office supply company followed by Black Sparrow work until 2am and all weekend. After about five years, he realized he needed help. Besides his wife, Barbara, who has designed the press’s distinctive book covers from home since 1966, Martin employs an assistant, a bookkeeper, and a book packer. The print shop he opened in Santa Barbara with typographer and fine printer Graham Mackintosh in the early 1970s employs six people.

Combining his background as a book collector and businessman with Mackintosh’s skills and literary connections, Martin made the savvy business decision to offer expensive, hand-bound limited editions of every title, as well as cheap paperback editions of the same work.

He began publishing short collections by literary lights such as Robert Duncan, Denise Levertov, Robert Creeley, Diane Wakoski, Sonoma County’s David Bromige, Joyce Carol Oates, John Ashbery, and Paul Bowles. Many Black Sparrow authors are heavy hitters who shaped the direction of American literature in the 20th century.

Selling to “a built-in group of maybe 50 booksellers all over the world” who took everything he published, the press turned its first profit in 1971. Martin has never looked back, though he did have to give up his unlisted telephone number. “I was horrified at the thought of people actually calling the office and trying to order books. We were too busy!” But he relented, and business improved. Word of Black Sparrow spread, and New York began watching who Martin was publishing.

The press has never borrowed money or applied for grants. “I’m a Yankee. If a thing can’t support itself, it’s not worth doing.” When short of funds, Martin sold the press archives–including bills and correspondence–to university library collections, leaving a paper trail for future researchers to follow. But the hard times are over. “For many years, we’ve done in excess of a million [dollars] a year. Some years we’ve done considerably more than that.”

Once established, Black Sparrow issued first 12 and then 10 books per year in print runs from 3,000 to 15,000. “We would print or reprint a book, about one a week,” most recently keeping 300 titles in print.

According to Len Fulton, who has published The International Directory of Little Magazines & Small Presses since 1965, many small presses never see a fourth anniversary. Calling 36-year-old Black Sparrow “an institution,” he says that Martin has accomplished every small publisher’s dream: discovering authors whose work readers seek out. “A small press to survive must have an obligatory notion of publishing. For instance, if you publish a book about cheese making, you’re not going to sell a lot of copies, but everyone who makes cheese will have to have a copy. . . . The market that it suits must have it–the same goes for poetry.”

And Martin has a knack for picking winners. “My whole thing was [that] I would publish only what I really liked myself, and there’s got to be two or three thousand people in the world who would agree with me.” But unlike many other publishers, Martin was able to get his books in those people’s hands.

“Writing has to have some fire and some soul in it,” he says. It must be “artful while appearing to be artless.” How does he know when he’s found a winner? “Sometimes you can read just the first story. I mean, how long do you have to listen to someone audition on the violin? . . . If they strike those first few notes, and they’re right on and they’re beautiful–great tone and great technique and real feeling for the music–you don’t have to go much further.”

Asked whether he still comes across good writing these days, Martin strides into another room and returns with Black Sparrow’s last book: Weep Not, My Wanton, short stories and poems by Maggie Dubris. “Wonderful writer,” he says, “just what I always looked for. I mean, if I was going to go on, she’d be one of my best stars.”

The press’ office and warehouse on mostly residential Tenth Street stand nearly empty now. In May Martin sold the rights to publish 49 titles by high-selling authors Paul Bowles, Charles Bukowski, and John Fante to the Ecco Press imprint of HarperCollins in New York. Well-respected David R. Godine Publishers in Boston bought rights to publish most other Black Sparrow titles and hauled away 66,000 copies of books. Gingko Press in Corte Madera bought the rights to titles by artist and writer Wyndham Lewis. Santa Rosa’s Treehorn Books swept up the remaining inventory.

Asked how he feels about selling rights to HarperCollins, part of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation Ltd., one of six media groups that own publishing houses worldwide, Martin says, “That’s just business.” He’s been impressed by the care Harper has shown. “Maybe they are a big conglomerate, but those people are so nice when you get down the line to the people who will deal with me.” After meeting Harper’s San Francisco sales force, he says, “What a fun, interesting bunch of people–completely familiar with all my books, as readers.”

Jeffrey Lependorf of the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses says that for a small press, being acquired by a large press “can turn out to be the best of both worlds.” The imprint can give personalized attention to authors and yet have the clout and distribution of a large publishing house.

Martin agrees, “I don’t feel pushed into some glacial dimension now–‘Black Sparrow’s going off to be put on a shelf and ignored’ or anything. I think they’ll do the best they can. I know it’ll be different, but they’ll do a good job.”

Despite the closing, Martin refuses to speak of Black Sparrow in the past tense. “The books are out there, and they’ll always be there, circulating. . . . Whatever I’ve accomplished, there it is. Forever.”

From the July 4-10, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.

And then he went ahead and changed and ruined Bukowski’s poetry right after he died. He’s shameless and a garbage person. The posthumous collections edited by Martin cannot be trusted.