The adventures of T’Challa, king of Wakanda and hero of Marvel’s newest blockbuster, Black Panther, gives solace to those burned by the calamities of our day, the shootings and the political strife. Television anchorpersons are enthusiastically but incorrectly calling Black Panther the first black superhero movie ever, even after decades of movies about mighty African-American fighters for justice that commenced in the 1970s wave of blaxplotiation films. What’s clear, though, is that this mammoth hit is a cultural event of some size, with an opening weekend box office of $235 million. By coincidence, on our own scene, a far smaller and less formidable African-American hero is being celebrated at the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, in an exhibit that runs through Aug. 5.

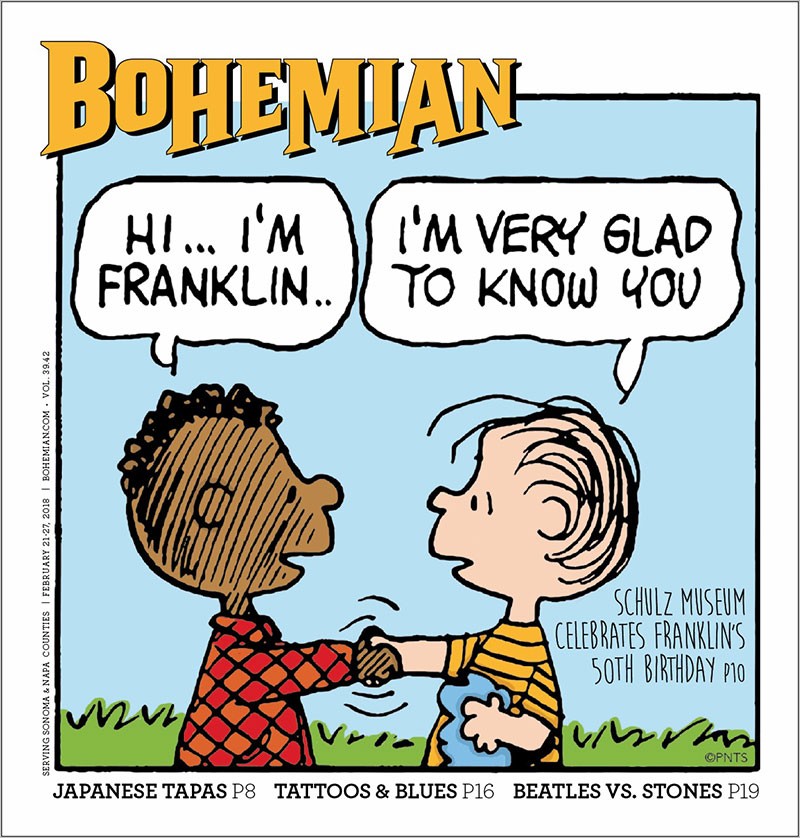

Charlie Brown’s friend Franklin Armstrong made his debut in Peanuts one half century ago this year. It happened in the summer of 1968, a distant mirror to our own times of violence and political division, in the weeks between the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. And it started with a letter. A schoolteacher from Los Angeles, Harriet Glickman, wrote Santa Rosa’s Charles Schulz. It’s a fan’s note for several paragraphs—”We are a totally Peanuts-oriented family”—before getting to the matter at hand:

It occurred to me today that the introduction of Negro children into the group of Schulz characters could happen with a minimum of impact. . . . I’m sure one doesn’t make radical changes in so important an institution without a lot of shock waves from syndicates, clients, etc. You have, however, a stature and reputation which can withstand a great deal.

According to Andrew Farago, curator of San Francisco’s Cartoon Art Museum and author of The Complete Peanuts Family Album, the cultural reach of Peanuts was huge when Franklin debuted.

“By the mid-’60s,” Farago says, “Peanuts was one of the most widely read newspaper comic strips in the world, and thanks to books, merchandise and animation, the characters’ audience and influence were growing exponentially.”

Schulz, however, wrote back to Harriet Glickman saying he wasn’t sure he was up to the task of writing a “non-patronizing” black character. Nevertheless, says Farago, Schulz “introduced readers to Franklin on July 31, 1968. Franklin and Charlie Brown hit it off immediately, reaction from readers and newspaper editors was overwhelmingly positive, and by that fall, Franklin was a regular member of the Peanuts cast.”

It is an emotional thing to see a museum dedicated to something that is so much a part of your childhood—and, hence, so much a part of the person you are now. The Schulz Museum gets 100,000 visitors annually. Though Charles Schulz died 18 years ago this month, his strip is still printed, in reruns, in hundreds of papers, and could conceivably—since Schulz left behind nearly 18,000 daily and weekly comics—remain a feature up to the extinction of the newspaper.

At the Schulz Museum are relics of the artist’s life: a re-creation of his studio and drawing board, and a childhood photo taken during the Great Depression of Schulz with the real Snoopy, a dog named Spike who was so ornery it ate glass.

The museum’s largest piece is a huge mural of 3,500 strips printed on tiles. From a distance, they comprise the image of Lucy van Pelt pulling away the football as Charlie Brown goes straight for the pratfall. The whole history of comics offers little as funny as the glee disguised as guilessness on Lucy’s face. That waltz between grifter and sucker—it never gets old.

“I was watching one of his last interviews, and Schulz was saying, ‘It makes me so sad that he never got to kick that football,'” says museum director Karen Johnson.

[page]

Johnson’s office is crammed with memorabilia of the very early days of the strip—a rubberoid figure of the piano-playing Schroeder must be over 60 years old. She shows me a notebook she kept from her teen years as a camp counselor some time ago. Linus was on the cover, offering the thought: “No problem is so big or so complicated that it can’t be run away from.”

“Peanuts was part of my lexicon,” says Johnson. “It informed me, and it helped me form friendships.”

On her desk are a couple of examples of the graphic marvel of Schulz. One four-panel comic has the miffed Snoopy slap-shotting his empty dog bowl at his alleged master—two of the panels being nothing but speed lines as the bowl meets its goal at Charlie Brown’s feet. The other is a framed strip, showing a dance between the phenomenal dog and a falling leaf. This is Peanuts at its most haiku-like wistfulness: a bamboo flute solo amid the brass section of the comics page.

Dedicating an exhibit to honor Franklin was a pretty simple decision to make, Johnson says. The museum’s staff considers anniversaries when figuring out displays, and the dates suggested the time was right. As for any controversy surrounding Franklin’s appearance, “there’s no evidence of that,” Johnson says. “It was all done without legislation, just correspondence between Schulz and a reader.”

The Franklin exhibit includes reproductions of that correspondence between Schulz, Glickman and her friends. There are some selected strips with Franklin, as well as a passing mention of comedian Chris Rock’s comment that the black kid in Peanuts sure didn’t say much. On the contrary, he did.

When first introduced, Franklin’s father was stationed in Vietnam, something not much discussed on the comics page. Like the color of Franklin’s skin, the mention of the war seemed to be enough for Peanuts: acknowledgement, but no stance-taking. In the strip’s final years, in the late 1990s, Franklin was a conduit for stories about his grandfather, including a dialogue about senior admissions at the aquarium, an unlikely springboard for a fine Carl Reiner–like punchline. (He’s only allowed to see the elderly fish.)

My pleasure in finally visiting the museum was mingled with realization that Schulz’s work still has its freshness and snap. “It’s timeless,” Johnson says, “all about us and our friends and our families.”

During the strip’s pinnacle years of the 1960s, the children of a Peanuts-mad nation had Charlie Brown as their spokesman, who gave them a word to describe their feelings: “I’m depressed.” Schulz’s strip was a stage for bemusement, isolation and failure, acute as often as it was cute. A friend says, “That strip was so sad.”

Was Peanuts sad? Schulz, a staff sergeant in Normandy during WWII, in charge of a light machine gun outfit, was a man of almost violent contrasts. He was a teetotaling Sunday school teacher in Sebastopol, yet he was remorselessly hyper-competitive, and could be iron-cold under that surface of “Minnesota nice” that he kept for life. He was superficially unaffectionate, but also wrote sugary love letters.

He was also an early and shrewd licenser, but kept sharp watch against any commercial dilution of his work. He ensured that the animated holiday favorite

A Charlie Brown Christmas

wasn’t “sweetened,” as the term has it, with a laugh track, and

he insisted on having Linus read

a passage from the Gospel of

Luke for an entire minute of animated time.

Schulz’s miracle was that he made a fortune working with negative space and smallness in a mid-century America that cherished splash and impact. Yet he was, more than anything, an anhedonist’s anhedonist. Schulz biographer David Michaelis quotes the cartoonist: “How do you account for someone being so unhappy when he has nothing to be unhappy about?”

The tension of his life is in his work. Hacks of every media tried to get Schulz to admit that he was, in fact, good ol’ Charlie Brown. They missed something—the ruthless, Germanic side of Schulz’s humor in the slapdown punchline. In Peanuts, mousetrap-quick punishment awaits those who dare to bare, or wallow, in their feelings, as when Charlie Brown’s “therapist,” Lucy, informs her patient: “You’ve got to stop all this silly worrying.” When Charlie Brown asks, “How do I stop?” Lucy responds with “That’s your worry! Five cents, please!”

[page]

As a craftsman, Schulz deserves honor, too. That seemingly tentative line that drew Charlie Brown is boggling. Every kid of a certain age knows this—copy Charlie Brown’s head, and it’s like trying to outline a smooth tangerine, only to end up with a drawing of a rotten grapefruit.

“We had the people from Blue Sky Studios here working on

The Peanuts Movie,” Johnson says. “They were trying to render that round head and that Picasso-like ear and nose in 3D. The simplicity of [Schulz’s] drawing was not simple.”

Ultimately, Franklin was a good first step toward integration, and it showed black readers that Schulz knew they were out there. Steps like these lead to the future, says Johnson. “Obama—well, if he didn’t actually mention Franklin, he said that Christmas didn’t start until Malia played A Charlie Brown Christmas.”

Reading Glickman’s letter at the museum, the last paragraph strikes me:

I hope there will be more than one black child. . . . [L]et them be as adorable as the others . . . but please . . . allow them a Lucy!

That, plainly and sadly, didn’t happen. Schulz couldn’t go there, even as television picked up the slack. “A black Lucy” makes one think immediately of LaWanda Page’s crabby Aunt Esther on Sanford and Son, wielding the Purse of Doom and the righteousness of Jesus with equal vigor. In support of her initial letter, Glickman included a note by one Kenneth C. Kelly, who as a black person added his support to Glickman. Kelly asked Schulz for “a Negro supernumerary” character.

At first glance, “supernumerary” is the perfect word for Franklin: a character whose innocuous qualities are there from his debut. In the first strips, he passes through the strange world of the Peanuts kids, from the odd fantastic beagle to the lemonade/psychiatrist stand, before going on his way. Inarguably, Franklin is what the museum called him, “A valued member of the Peanuts family.” But the South Park gang, who named their only black kid character “Token,” also had a point.

Farago argues: “I’m reluctant to call Franklin a token, since Schulz wasn’t under any pressure from his syndicate to integrate the strip. Franklin’s introduction was potentially going to lose more newspapers than it was going to gain, and I’m sure that Schulz brought him into the strip because he knew it was the right thing to do.

“There were literally millions of eyes upon Franklin every day when he was introduced in Peanuts,” Farago continues, “and as the first (and, ultimately, only) black character in the strip, I think Schulz felt the need to make sure that Franklin was a positive role model, almost to a fault. Unlike the other characters in the strip, Franklin was free of neuroses and hang-ups and personality defects, and was almost too well adjusted. Personally, I think Franklin is the kid that Charlie Brown might have been if he hadn’t been so wishy-washy: popular, content, reasonably confident in his own abilities.”

A rival strip went further: “One of Charles Schulz’s good friends in Northern California was an African-American cartoonist name Morrie Turner,” Farrago says. “Morrie was dissatisfied with the lack of black characters on the comics page, and this was a frequent topic of conversation between him and Schulz.

“With Schulz’s encouragement, Morrie launched his comic strip Wee Pals in 1965, the first nationally syndicated comic strip to feature an ethnically diverse cast of characters. I don’t think Morrie ever denied that his strip owed a lot to Schulz, but Peanuts was such a successful, game-changing strip that it’s hard to find a strip launched after 1960 that wasn’t influenced by it.”

It is possible to overlook the importance of small symbols in a time of anger and fracture, whether the annus horribilis is numbered 1968 or 2018. There seemed little comment last year when in Spider-Man: Homecoming, our hero uses his strength and webs to hold together a ferry called Spirit of America, split into left and right—well, port and starboard—halves.

T’Challa is also the kind of figure who could bring us together again (see Film, p18). And Franklin Armstrong of Peanuts is another symbol of inclusiveness, evidence of the strength of something as little as lines on paper.