Marinwood is a quiet suburb between San Rafael and Novato, where three-bedroom homes with backyard pools circle green, undeveloped hills. On a Wednesday evening in June, it was also the setting for a town hall meeting that would later be likened to a lynch mob.

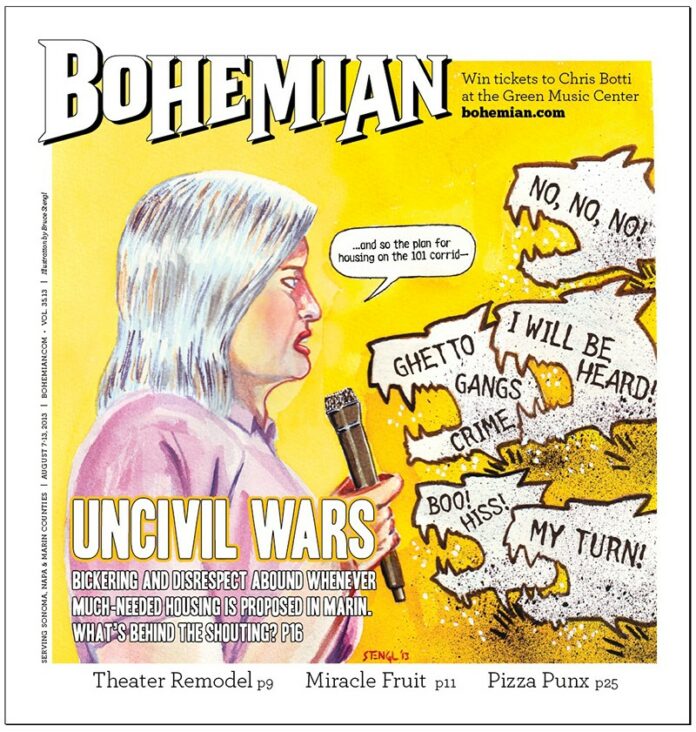

Held by Supervisor Susan Adams, the gathering at the Marinwood Community Center on June 26 began with a simple presentation on proposed zoning changes but quickly devolved into hysterics. Residents packed the large room, standing in doorways and leaning in open windows, waving signs that said “Democracy, Not Autocracy” and showed apartment homes crossed out. Shouts of “No, no, no!” drowned out the official when she tried to speak. One woman commandeered the microphone, taunting Adams by pretending to hand it back again and again as the supervisor grabbed at air.

Finally, in a line that would echo infamously through the fair-housing community, real estate agent Melissa Bradley told Adams she’d “volunteered Marin for the ghetto.” Throughout the hour and 45 minutes, Adams tried to answer questions, looking flustered as she lost control of the room.

That housing is a big deal in no-growth Marin is hardly news. Spurred by the perceived threat of apartment complexes, communities in the wealthy county have so far neglected to zone for low-income housing, in violation of state law, and then been sued; zoned for low-income housing on the sites of existing businesses that may not intend to sell; and, in the case of Corte Madera, withdrawn altogether from the regional planning agencies that oversee this kind of zoning.

Still, recent months have seen this polarized debate give rise to behavior that is downright bizarre—not just in the form of meetings like the one described above, but also in a recall effort against Adams, which would cost as much as $250,000 and oust the supervisor from office only months before she faces a general election anyway.

How did this happen? After all, as Carla Marinucci pointed out in a recent San Francisco Chronicle piece on the county’s current incivility, Bush-era Marin County was supposed to be a Greenpeace mecca of laissez-faire hippies soaking in backyard hot tubs. It continues to be caricatured as a rosy-vibe utopia policed by the handholding Kumbaya Patrol, not a place where mob mentality sweeps town halls.

Is this chaotic mass opposition to housing the byproduct of top-down leadership on the part of local government, as some claim? Is it hysterical fear of Big Development in the wake of mortgage plummets, national bailouts and an economic machine that many no longer trust? Or is it really as ugly as it looks from the outside—wealthy suburban privilege at its worst, organizing to keep renters, low-wage workers and recent immigrants far, far away.

A common theme at meetings in Marinwood and elsewhere is the notion that information is being withheld. Carol Sheerin, one of the founders of the Susan Adams recall effort, says the anger on display in Marinwood comes partly from a feeling of futility: suddenly there appears to be all this compounded development, without the type of public process neighbors feel that they deserve.

“Just in general, people feel like they have not been made aware,” she says.

Stephen Nestel, the founder of SaveMarinwood.org, seconds this. “Our community, like most around the Bay Area, should have been brought into the planning process at the very earliest time, about 10 years ago,” he writes in an email, adding, “This is undemocratic and an affront to citizens.”

So what, exactly, is being proposed in Marinwood? Is it the acres upon acres of concrete, high-rise slums that many speak of as though the first cinderblock is about to be laid?

No, it isn’t. As Adams explained at the meeting, one developer has turned in an application to renovate the derelict Marinwood Plaza, and that application will be subject to all the public processes—EIR certification, design review—that developers are subject to under California law. But what has so many homeowners up in arms is a little thing called a PDA, or a priority development area, and that concerns zoning, not actual development.

A word on zoning. Under state law, government entities are supposed to zone their communities cyclically to plan for future growth. (These same entities do not build housing, which is the domain of private or nonprofit developers.) One of the ideas behind housing element law is integration. Public entities are supposed to make sure that zoning does not “unduly constrain” development of multifamily housing, where people who cannot afford to buy a three-bedroom home with a yard can live. Government is supposed to match projected growth for all income levels with fair zoning.

[page]

This is a huge problem in Marin County, where, as one advocate wrote, the poor are “zoned out.” According to a county document prepared for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, multifamily housing is clustered in only a few areas like Marin City and San Rafael’s Canal District, where racial and ethnic minorities tend to live. According to a study funded by the Marin Community Foundation, 60 percent of Marin’s workforce lives out of the county and commutes in daily, holding jobs that tend to pay under $50,000, like residential care and retail.

The study also notes the environmental hazards of such a freeway clog—an unnecessary 2.4 million pounds of carbon pouring into the atmosphere every day. This is a rough equivalent—daily—to the emissions produced by 42,000 U.S. households in a year.

As Adams points out, none of the zoning in Marinwood has been proposed in secret. Though audience members at the town hall shouted “You did not come to this community, you did not notice this community!” she replied that every meeting where potential zoning was discussed had been done in a public. Discussions over the housing element update—public. Board of supervisors meetings, where Marin’s 101 corridor was discussed as a place to concentrate future growth because so much of the rest of Marin is preserved as open space—public.

“There have been public meetings, with audio streaming and webcasting, so you can see not only all the documents discussed, but the conversation around those documents,” she tells me on the phone.

She’s right. I’ve been covering land-use issues in Marin for three years, and none of the zoning changes discussed at the Marinwood meeting were new to me. Still, audience members seemed to feel that public process wasn’t enough.

“It’s not our full-time job!” one audience member yelled. “It’s your job as supervisor to come to us when there are major land-use issues at stake in our community!”

There was a chorus of applause.

I asked Sheerin how she thought Adams should have “noticed” the Marinwood community. “I can’t say putting it in the newspaper, because no one reads the newspaper,” she says. “Maybe sending out postcards.”

In a background conversation, another person at that meeting told me nearly the exact same thing: “Nobody reads the newspapers,” she said. “Maybe if it had been on TV.”

As Adams says when I told her about these responses: “‘Notice’ is a two-way street.”

Another common theme at the Marinwood meeting, and others that I’ve covered, is more understandable. It’s the notion that the numbers governing this whole process are off.

Two speakers addressed this eloquently.

When Adams stated that a “low-income” designation in the wealthy county caps at around $65,000, one man protested, “We are that bracket.” Another man from the crowd called out, “That’s us!”

It’s true. Just as the tech boom has wildly inflated rent in San Francisco, Marin County’s extremely high median earning—$130,000—has hiked the low-income line past what many living in market-rate housing make. And the idea of somehow subsidizing families making more than you do in low-income apartments is hardly popular.

The supposed “low-income” number comes from an organization called ABAG, which, lately, seems to be Marin County’s least favorite four-letter word. The acronym, short for the Association of Bay Area Governments, refers to the planning organization that puts out another acronym, the RHNA. This Regional Housing Needs Allocation is the all-holy number of units that each government needs to zone for every few years, to match projected growth.

[page]

If this number were some kind of omniscient data set, all would be well and good. But it’s not. Spurred by Mark Luce, the president of ABAG who called the process a “black box” when I interviewed him last summer, and Bob Ravasio, council member of Corte Madera and a member of ABAG who told me “If you find out how the RHNA works, let me know,” I drove to Oakland to visit ABAG. There, I sat in an office and looked over at least 10 sheets of paper as planning director Hing Wong explained the “formula” used to calculate RHNA. It took an hour. And it’s wasn’t a formula, really—it was determined by months and months of meetings, in which government officials, fair-housing lawyers, developers and transit workers decide the “fair share” of how much each region should get.

But though ABAG has a reputation for strong-arming development onto unwilling towns, the RHNA process can be arbitrary in unexpected and troubling ways.

Because housing, particularly affordable housing, has historically been so unpopular in Marin, elected officials can push back against this fair-share mentality. And thus, despite its high in-commuting numbers, parts of Marin received unusually low numbers in the most recent cycle, compared to recent years.

As we reported last year, Wong told me that in Novato, this was at least partly because “a councilwoman wanted very low numbers.”

The lack of good, unbiased data means that vast conspiracies have sprung up in which Marin’s lack of affordable housing and clogged freeways aren’t really problems—they’re considered smokescreens for developers who just want to make a buck.

“Everyone says ‘You’re in the pocket of the developers,'” affordable-housing advocate Lynne Wasley says. “I’ve never been given a dime.”

Op-eds are written in which supervisors, characterized as “well-to-do progressives,” and developers seem to be in cahoots. And during the Marinwood meeting, Bradley and several others alluded to the study conducted by Marin County for HUD—which found that minorities and multifamily units had been clustered due to discriminatory zoning—as an affirmative action document, implying that it was a tool to bring in “underrepresented minorities [from] outside Marin County.”

And so a strange and sour attitude comes into play at public meetings, which tend to be overwhelmingly middle-class and white. It’s an attitude that doubts the very existence of low-income workers and residents in Marin—an attitude that might explain something like the farcical post on Nestel’s SaveMarinwood.org.

“Wanted” it reads. “Gay Eskimos for Marinwood Village Affordable Housing Complex.”

At Novato’s affordable housing meetings, which I covered back in 2010, it took the form of comments like “I heard that we recruited people from Richmond to come here tonight to fulfill our need for affordable housing” and “All of these people who need a place to live, where are they now?”

And the answer mirrors this systemic issue. They’re not at evening Marin meetings, because though they work in Marin, they don’t live there.

Or else, as a troubling press conference recently implied, they’re too scared to come.

At a very different meeting than the ones described above, a group of fair-housing advocates and grass roots organizers came together in the Marin Civic Center garden on a Tuesday morning. They spoke quietly, waited their turn to speak and punctuated each comment with well-mannered applause. No one hissed, booed or called the police.

And the tenor of the gathering felt like a PTSD support group.

John Young, leader of Marin Grassroots, recalled talking to a colleague during a public meeting—before someone called the sheriff and asked that he be kicked out. A black man who describes himself as a big guy, Young said he felt afraid.

“This was a room full of 200-plus European Americans,” he says.

An Asian-American man shares a similar experience. He recalls getting up to speak in favor of affordable housing and being heckled with the words: “You don’t belong here.” Wasley, who was in attendance, says she hasn’t been to a public meeting in Novato in two years, after being booed and hissed in numerous town halls. She was even hissed at the grocery store wearing a sticker in favor of affordable housing, she says.

And then Gail Theller, a spokesperson for Community Action Marin, says something that does not bode well for the future of public discourse in Marin.

“The public areas in which these discussions are taking place have gotten to be so threatening that I’m unable to organize a group of people who are low-income to come,” she says.

The group announced that it was going to write a letter to Gov. Jerry Brown about the fact that all sides of Marin’s housing debate are not being heard. But in the meantime, meetings take place in suburbs like the one described at the beginning of this piece, where homes sell for an average of $650,000 a pop and beautiful community halls are packed with angry people, holding signs and shouting about apartment buildings.