My family may have brought me to this country physically, but what really brought me here was the United States itself. This country created the situation that prompts immigrants to migrate here from Mexico and other places. Historically speaking, many people in the Americas have migrated, or have been forced to migrate, because of political or economic factors caused by the United States—a country that I no longer choose to call “America.”

America is a continent with a diverse range of people who have been confronting colonialism and imperialism for a long time. I do not think the United States was ever a democracy, since democracies are for the people and this country has not, for a long time, been for the people. It is not for the people of Latin America or for the indigenous people of North America. I am technically a North American. I have Spanish and indigenous blood.

How can I be multiple types of people in this country at the same time? I am at risk of being grabbed by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents even as I am protected from deportation through the actions of the previous president. I’m making art and being in the art world. And, I am just me.

CROSSING THE BORDER

My family migrated from Tabasco, Mexico, to Santa Rosa at the turn of the last century, when I was 11 years old. My parents had decided to move for economic reasons, but it was difficult to get a visa, so we came here through the means that many people come to as a last resort. Our mother took us to Tijuana where one of our aunts was waiting, a woman I had never met before. In this house, a large, round woman called a “coyote” picked us up. The coyote had skin burnt from the sun and dark, curly hair. She drove a minivan.

My mother gave us sleeping medicine on the night we left, and we got into the coyote’s van and she drove us across the border. We were drugged with Tylenol so we wouldn’t talk to the border patrol at the checkpoint. The driver pretended that we were her kids. We were young and I was the oldest, and we could have been her children.

Once we were across the border, I woke up and asked where we were going. My worry was that the coyote wouldn’t give us back to our parents. She could easily have kidnapped us, but she took us to our aunt’s house in Los Angeles, where we waited for our mother.

BETWEEN TWO WORLDS

My first meal in the United States—I remember it clearly—was pineapple pizza with Coca Cola. I remember eating it in a beige apartment served by our very nice aunt. She took care of us until our mother got there—she had to cross the border by foot, and never arrived. But eventually our father did arrive, and he took us to Santa Rosa where a second aunt lived. We stayed in her living room for about a month until we were able to find our own place. We met up with my mom later. She still lives in Santa Rosa.

I turned 12 that year, and that summer one of my new friends took me to the Sonoma County Fair, and we rode the roller coasters. That was my birthday present.

I attended seventh and eighth grade at Lawrence Cook Middle School in Santa Rosa. It was very challenging because I had only been through the second grade in Mexico. When my parents left Mexico with us, I was very upset because they were taking me away from the school where I’d been promised that I’d stay through sixth grade—ironic, since I ended up moving up to seventh grade in the United States.

[page]

My teachers helped me survive middle school and prepare me for high school. I went to Elsie Allen High School and graduated from Santa Rosa High School in 2006 after transferring there in my senior year to focus on studying art. I think the schools are making strides in serving students from different socioeconomic background like me. They are starting to celebrate Latino culture, but there are still some gaps. There was a very supportive community in the schools. Students could access college-prep programs for Sonoma State University. But, culturally, there was also some negativity toward us as students. During lunch one day, a student said he wanted to rape an illegal because he knew she wouldn’t call the police.

I was very shy as a teenager, something people don’t associate with me now now. I spent most of my time creating art while I learned English. When you’re a teen, it’s hard to come to terms with who you are, and as a person of color, a perception of who you are is often imposed on you. Biculturalism is a struggle for many immigrants. I was trying to embrace my culture while living in a new one.

ENDURING QUESTIONS

When I was in high school I wrote a paper for the National History Day competition on the history of immigration in the United States. I wanted to understand how it came to be that immigrants here are oppressed, and what it was that disqualified immigrants from accessing basic human rights. Why does one generation of immigrants after another get treated this way? At the time, I couldn’t write well in Spanish or in English. I just had that question, and it’s one I’m still asking today.

I left the North Bay for New York to go to college. Now, at 28 years old, as I sit here in Christopher Square, in Manhattan, I believe the answer to my old question has to do with religion and money. People deemed second-class citizen do the labor and are kept in poverty because this country is not an equal system for everybody. Too many U.S. citizens stand by their religious beliefs or economic ones as they tell other people how to live their lives and declare them “illegal.”

That has become very apparent to me—and all the more so recently, as I’ve been forced to engage with the realities of Trump’s immigration crackdown. I have to stay out of trouble and I have to make sure I am following the rules, and that where I’m living is safe—both physically and legally. Because of Trump, I’ve moved to a new place, closed my art studio and I put a lot of my artwork in storage to keep it safe.

THE POWER OF ART

After graduating from high school, I attended Santa Rosa Junior College, which gave me a foundation in government, mathematics and art. I transferred to Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute in 2011 on a partial scholarship and graduated with a BFA in 2013, thanks in no small part to the many people who bought my artworks and helped me get through school.

During my time at Pratt, I created a nonprofit program called One City Arts. Now it’s a permanent program at the Luther Burbank Center for the Arts that teaches art to children from low-income backgrounds.

The arts are a leveling factor. Arts and education are important to improve our lifestyle, but they also enhance our sense of belonging in a country where immigrants too often feel displaced. That sense has only gotten worse in recent days. Nationalism and white supremacy have long served to erase the history of the indigenous people of Americas and oppress the immigrant community—a community forced to migrate to a country, for economic or political reasons, that grows increasingly unwelcoming.

I graduated from Yale University with an MFA in painting in 2015. That was something I’d never have expected to achieve because of my background. My time at Yale taught me many things and introduced me to a lot of people and ideas that have shifted my perception of who I am and my perception of what my work is about. Everything I am has been shaped by the United States. And it has been shaped by its people—the people who are always there for me, those who have been aggressive toward me, who have stereotyped me, who forced upon me the internalized oppression of the undocumented that I live with and am trying to overcome.

[page]

THANKS, OBAMA

I was able to go to Italy last summer thanks to the visa waiver program, which was provided by President Barack Obama’s executive order designed to protect “Dreamers” like me from deportation. Thanks to him, we could travel abroad for our studies without fear that we wouldn’t be able to return to the United States. I came forward and registered as a Dreamer when Obama announced the waiver, which discouraged ICE agents from targeting the children of the undocumented. Obama’s 2014 waiver represented a “spiritual pardon” for the former president given the number of people he deported in his presidency.

In Italy, I saw the great works of the Italian Renaissance, but also glimpsed the country’s economic and refugee crisis. I didn’t want to go back to the United States, and I felt the weight of anti-immigrant ideology forced upon me when I arrived back here and went through the immigration checkpoints. I was put in an empty, gray room for questioning and was ultimately allowed back into the country. I rode the train home with somebody I had just met who waited for me on the other side of customs. I wanted someone to wait for me just in case I didn’t come out—in case I was threatened with deportation.

NOT MY DREAM

I never wanted the American dream. It was never my desire. The American dream has been stabbed into the heart of the Americas, the American continent, and it has shaped who I am. It has destroyed many families and it continues to do so. The American dream is a tool used to oppress. This is where I find myself now: trying to create art that can heal me from it all, art that is just, open, contradictory, but also that can try to help.

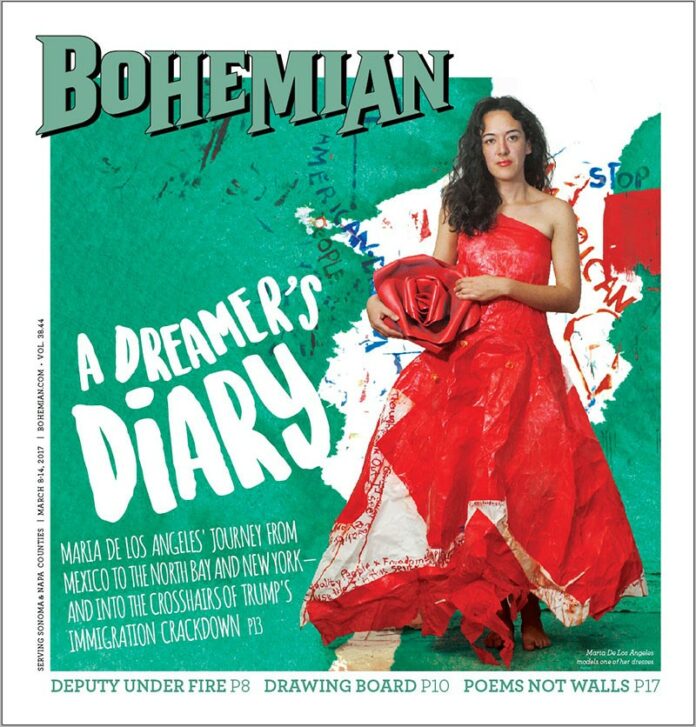

Identity is a subject that excites me as an an artist, since art goes beyond walls—it crosses all borders. I am excited to talk about identity and to figure out identity through fashion. That’s my big plan—to create a couture fashion line. I’ve been interested in this since I was young, when my grandma gave me hand-tailored dresses that she confiscated from my aunt because they were too short. Given the renewed anti-immigration push by Trump, I’ve been in a dark place and I want to come back to a positive place with positive acts—using my art as an extension into couture, and the connection to identity.

This is the issue Dreamers face now: identity and internalized racism and oppression. For me, those things are imposed on the body. I am creating wearable couture sculptures which have imagery that addresses bicultural identity and which helps free me from the internalized oppression of “illegality.”

I know there are dangers in sharing my story. Now the politics and the beauty I see are all going into the garments that I make. I need to deal with my emotions that way. There is such darkness now. We need something beautiful.

The author would like to thank Belle O. Mapa for her assistance in preparing this article, which is also drawn from a follow-up interview with news editor Tom Gogola.