For most kids growing up in post-depression, World War II–era East Los Angeles, becoming a professional artist wasn’t an option. “Most of my friends went into the service and ended up in menial jobs,” says Roberto Chavez, born in the Maravilla area of East L.A. in 1932. “A lot of the younger kids in the neighborhood ended up in prison or strung out on dope. The medium of art helped me to see other possibilities.”

Against the odds, Chavez became a life-long teacher and painter. It’s an accomplishment that Chavez might never have seen if he’d gone the way of most of the other kids from his hometown, a once diverse, working-class neighborhood with a large Mexican-American population. From Nov. 15 through Dec. 13, the Robert F. Agrella Gallery at SRJC features the first-ever Chavez retrospective, an exhibit comprising 60 works.

Encouraged by his family and teachers from early on, Chavez took art classes in high school and went to Los Angeles Community College before transferring to UCLA, where he received a master’s in art. It was a path that took him into teaching, a profession that Chavez practiced for over 40 years; it led him from the halls of East Los Angeles Community College, where he helped found one of the first Mexican-American studies departments in the country in 1969, to teaching in juvenile halls and women’s prisons across Southern and Central California. He retired to a tucked-away corner of southern Arizona two years ago.

“Luckily, I was able to make a living doing something I really believed in, which is that art can be an influence of change for people,” says Chavez, who also spent 10 years in Fort Bragg in the ’80s and ’90s. “I had myself as proof.”

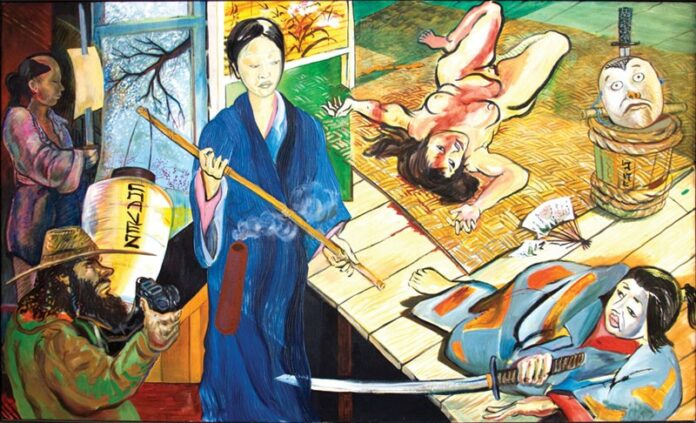

Like his childhood home, with its mix of Jewish, Mexican, Armenian, Italian, Russian and Japanese populations, Chavez’s art takes hybrid forms. Formed from a hodgepodge of influences—from European abstract expressionists to Mexican artists José Clemente Orozco and Rufino Tamayo—Chavez’s work plays at the intersection of life’s joy and pain, capturing the simpler moments (a mother sitting peacefully in a chair, a still life with fruit) along with war scenes of naked, bloody bodies.

Paintings like Belsen Landscape from 1957 have a dark claustrophobia in the vein of Norwegian expressionist painter Edvard Munch. Considering that both the Mexican and Jewish populations came to Los Angeles to escape violence—for Jews it was persecution in Eastern Europe, and for Mexicans (including Chavez’s own family) the danger caused by the Mexican revolution—the subject of war isn’t surprising.

Later works, like Late Summer, a light-filled watercolor painted in 2007, linger in the world of texture and space rather than human struggle. In another nod to European art, Chavez writes in a book complementing the new retrospective that it was an exhibit of Renoir’s flower paintings that he viewed as a young artist which opened his eyes to the medium’s possibilities.

“It helped me to see the potential of paint,” he explains. “They seemed to be not pictures of flowers, but rather paint that was alive on the surface of the canvas that created patterns, patterns that conveyed the forms of the flowers to the eye. I wanted to make paintings that had that kind of magical energy.”

In 1961, Chavez began to exhibit his work at the then-new Ceeje Gallery in Los Angeles. Located on La Cienega, the gallery specialized in the expressionist and dramatic work of figurative painters, many known for pushing the margins in a city that was focused on abstract, streamlined art. Over the years, Chavez had both solo and group shows at the adventurous art space.

“I was aware that we were an odd lot that started that gallery,” he recalls. “We were also aware that there were different things going on elsewhere in the city.” From 1961 to 1970, the gallery offered an alternative to other Los Angeles galleries, which tended toward a rehash of the New York art scene, explains Chavez.

The compulsion to be true to his own vision and creative impulse, without paying much, if any, attention to what’s commercially successful, is a vein that continues to run through Chavez’s work even as he enters his eighth decade.

“The kind of art that I do and that I teach, there’s not a big place for it in the world today,” he says, when asked what advice he’d give young artists. “It’s all commercial and celebrity, and that’s all bullshit. Follow your heart and don’t look for rewards. Do it because you want to do it.”