Nutty Professor

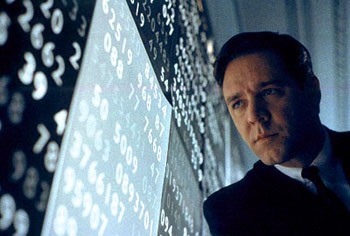

Russell Crowe gnashes Nash in ‘A Beautiful Mind’

By

The schizophrenic delusions of John Forbes Nash, Jr., according to his biographer Sylvia Nasar: “In his mind, he traveled to the remotest reaches of the globe: Cairo, Zebak, Kabul, Bangui, Thebes, Guyana, Mongolia. . . . He was C.O.R.P.S.E. (a Palestinian Arab refugee), a great Japanese shogun, C1423, Esau, l’homme D’Or, Chin Hsiang, Job. . . . Baleful deities–Iblis, Mora, Satan, Platinum Man, Titan, Nahipotleeron, Napoleon, Shickelgruber–threatened him.”

And he lived in fear of the apocalyptic Day of Resolution of Singularities.

Nash, subject of the film A Beautiful Mind, was the Nobel Prize-winning math genius and madman whose mental illness interrupted a brilliant career. This career included such discoveries as Nash’s equilibrium in game theory and Nash’s theorem about the embedding of manifolds in Euclidean space. The illness was tragic, but at least Nash was spared, for a time, from falling into the hands of screenwriter Akiva Goldsman and director Ron Howard. That time has ended.

Not since the film Awakenings has the career of a scientist been subject to such terminal dumbing down. Russell Crowe brings a certain sway to the part of Nash–he’s good with bemusement and panic. Still, Howard and Goldsman’s anti-intellectual approach to the material ensures that A Beautiful Mind remains a disease-of-the-week film shot in the dullest colors. Crowe’s virility is shorted out here for “Oscar-caliber acting”: the standard sloppy, shoe-gazing, awkward little boy portrait of an intellectual. His Nash is redeemed by true love (Jennifer Connelly, gorgeous as always, but unable to draw a bead on her shying co-star).

The madman’s deliriums–which were more vividly suggested in Pi, no doubt inspired by Nash’s troubles–are presented here as a plain Cold War spy drama, featuring Ed Harris as a spy in a snap-brim hat. It’s a clever strategy to make cinema out of the career of a man who spent most of his life staring at a chalkboard. Still, what Nash accomplished could have been illustrated so much more thrillingly.

Yes, the movie is different from the book, which outlined a fiercely competitive academic world that sometimes strained the sanity of those who lived in it. The movie-shall-be-different-than-the-book law doesn’t mean all adaptations of real life must be crapified. Ours is an era when you can tell any kind of story in a movie, so there’s no excuse for deleting troublesome subjects, such as Nash’s pre-breakdown sex life, which included an illegitimate child and several male lovers.

The “brute mental power” a colleague described in Nash is ignored in creating this fake prestige movie, topped with a glop of derivative and repetitive James Horner music. Appropriately, it’s a soundtrack that’s enough to drive anyone insane.

From the December 27, 2001-January 2, 2002 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.