Drinking red wine has kept me out of most trouble, or at least in the kind of trouble I can manage for most of my drinking career.

When it comes to cocktails, however, I’m a dabbler. I’m allergic to hipness and am a mixologist avoidant.

But I know that one of the secret ingredients of a good cocktail is the ambiance in which it’s served, and I knew where to go for this assignment.

Tucked into a ’30s-era building in an inauspicious corner of Santa Rosa’s Historic Railroad Square is a structure with the distinction of being the oldest “freestanding, continuously operating restaurant in Santa Rosa.” This is per their PR. I’m not sure why “freestanding” is necessary, but it’s true—it’s freestanding.

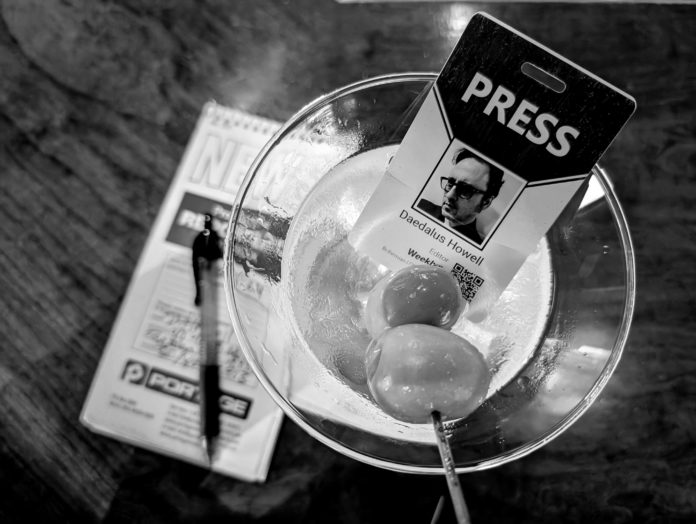

Purchased and brushed up by restaurateurs Mark and Terri Stark, the spot reopened in 2008 as Stark’s Steakhouse and was later re-christened as Stark’s Steak & Seafood in 2011 when the tide rose and surf met turf. But what got me was the name of the restaurant’s holding company—Stark Reality—and their website had a journo-friendly “media center.” Those seeking the press would be wise to follow their example—this is how editorial decisions are really made. A decision I didn’t make, however, was what I was drinking—a dirty martini.

“I have never understood how a serious martini fancier could destroy the drink’s sensual flavor by plopping in a salty pimiento-olive or one of those rancid miniature cocktail onions (which immediately transforms a Martini into a Gibson),” wrote James Villas for Esquire during its mid-’60s, Mad Men era heyday.

If Villas were on the bar stool next to mine at Starks, I’d explain the Gen X need for a certain kind of controlled corruption. As a generation, we’ve collectively mistaken transgression for transcendence. “It’s because we never went to war,” someone once tried to explain to me.

For us, a dirty martini has the same attitude as Madonna spray-painting the genitals of classical statues in her “Borderline” video. Of course, we didn’t know that then or appreciate the classy iconography of the martini until the following year when Roger Moore ordered one as James Bond in A View to a Kill, adding his crabby admonishment that it be “shaken, not stirred.” Try this at a bar. Bartenders love it.

A bearded, Millennial-aged man took the stool next to mine. His wife sat on his other side. They each ordered martinis, confidently specifying both brand and garnish—Hendricks gin with a lemon twist for him and something else for her, which, though out of earshot, was redolent with syllables and seriousness. And gin.

Yes, gin.

It’s made from a grain base and infused with juniper berries and other botanicals. Vodka, martini’s frequent and inferior interloper, is made from a tuber dug from the pitiless and frozen tundra. Gin is for wits and wags. Vodka is the spirit of potato-eating peasants. A vodka martini is a declaration that one expects less in life. A real martini (it’s frankly redundant to mention gin as an ingredient here) is the blood of the gods.

Some knew this intrinsically—Robert “Now I Am Become Death, The Destroyer of Worlds” Oppenheimer, father of the atom bomb, had his own martini recipe that included a glass rimmed with lime juice and honey (but conspicuously no uranium). For a Barbenheimer Martini, add a jigger of Pepto Bismol.

Curious, I asked the young bartender the make and model of the gin in my dirty martini. It was New Amsterdam, but she reminded me that it didn’t really matter since any nuance is effectively destroyed due to, as she put it, the “olive juice.”

Olive juice—by which she meant the brine that makes a dirty martini dirty. I’ve since learned it is now bottled and sold in “premium” form by such brands as Dirty Sue and Filthy.

I first encountered the term “olive juice” at a film festival in 2001 when Survivor host Jeff Probst seized his career ascendency to direct a lukewarm thriller called Finder’s Fee. In it, there’s a poker game, a stolen lottery ticket and a morally troubled protagonist unable to say “I love you” to his girlfriend.

Instead, he dramatically says “olive juice” through a rain-streaked window, which looks like “I love you” to her. It’s a maudlin, chicken shit moment I’ve never forgotten.

Splendor in the Glass

Though the martini’s invention can’t be pinpointed to a particular year (most experts agree it was sometime in the aughts of the 20th century), we do know when the iconic glassware was introduced to the culture.

The martini glass as we know it, with its iconic V-shaped bowl and long stem, was first introduced at the 1925 Paris Exhibition. Thus, this coming year marks its 100th anniversary. If one needs a news peg, this is it. It’s an elegant glass for a more civilized age.

To properly operate the glass while writing, hold it by the stem like a pen. Bring it slowly to your lips (otherwise, you will wear its contents). Sip. With one’s other hand, jot down a bon mot. Sip. Scratch out the original bon mot and replace it with an improved version. Laugh out loud—to yourself. Repeat until you have 900 words.

With a martini in one hand and a pen in the other, one’s fingers may resemble the manner of the Buddha’s Vitarka mudra, which suggests the continuous flow of energy and wisdom. In time, this may become a continuous flow of gin and vermouth.

But as New Yorker writer James Thurber observed, “One martini is all right. Two are too many, and three are not enough.” I had two and was beginning to rethink the second. The man next to me ordered another. His wife, however, downshifted to a pinot noir. Smart. I should’ve done that. I was beginning to reel.

Because, in the end, this is wine country—and wine is our first love, or at least we say it is. After my dalliance at this end of the bar, I was ready to return to wine as well.

Oh, wine. It’s you. It’s always been you.

Olive juice.

As always, so very clever and pithy. FYI if you switch to shrubs you can love dirty olives all you want with no (immediate) consequences. Then all you gotta worry about is the tart-ness.

“A Martini,” said my father Patrick, “is a polite way to drink straight gin in public. And an alcoholic is someone you don’t like who drinks as much as you do.”

Cheers!