Yada Yada

Wurtzel’s ‘Bitch’ an uncertain manifesto

By Traci Hukill

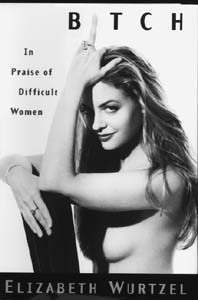

IF ELIZABETH WURTZEL’S luck holds, this year’s $64 million pop-culture question will be: Is the cover of Bitch (Doubleday; $23.95), the young author’s feminist follow-up to Prozac Nation, keenly ironic or just a witless attempt at sass? There’s no doubt that it’s a marketing coup. Wurtzel’s svelte, naked babehood (with nipple Photo-shopped out), the manicured hand that lazily flips the reader off, and the bored sneer on her delicate face have won this book unusually widespread attention.

But how those features relate to a philosophy separate from Katie Roiphe’s and Naomi Wolf’s “do-me” style of seduction-as-power-grab feminism remains unclear, muddled by Wurtzel’s intellectual confusion and hyperventilating prose. Wurtzel says that feminism has failed us, or at least got us stuck between an ideological rock and a desirable hard place, but this book’s frustrated rants, uncertain message, and simpering conclusion don’t help to point the way free.

Wurtzel is certainly capable enough. She’s smart, observant, educated, and remarkably adept with language. But she’s grappling with a complex problem–how women can get their emotional needs met without bringing on themselves the wrath of God, the media, men, and other women–armed with a myopic strategy, one too focused on a coterie of starlets and professional brats.

The introduction, “Manufacturing Fascination” (an apparent reference to MIT media critic Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent), concludes with a thesis statement: “This is a book about women who wrote and write their own operating manuals, written in the hope that the world may someday be a safer place for them, or for us, for all women.”

What follows is a who’s who of history’s bad girls–Delilah, Amy Fisher, Anne Sexton, Courtney Love–their apologies penned by Wurtzel herself, interspersed with stories of victims no less famous than Sylvia Plath, Princess Di, and Nicole Brown. Most are excused for their mistakes, tantrums, and marriages and then molded into examples of how the world punishes “brilliant creatures who shine”– except for Hillary Clinton, whom Wurtzel lambastes for not demanding a salary and for ignoring Bill’s indiscretions. However, the author simultaneously praises her for having “succeeded [at marriage] where so many others have failed or given up or snapped.”

Others–Paula Jones and Pamela Harriman most notably–Wurtzel shreds, and her litmus test for who merits exoneration and who deserves public humiliation defies analysis.

If Wurtzel’s logic suffers unnerving mood swings, her brilliant but manic writing should be committed. Pretentious and obfuscating allusions to history and popular culture, parallel-structure sentences that ramble on for most of a page, too many personal confessions, and a bad habit of prefacing her opinions with the word look, as in “Look, I think many people have rescued themselves from this game,” bespeak the mistaken notion that people are privileged to read her self-absorbed, stream-of-consciousness meandering through difficult intellectual territory.

It’s like having a precocious 13-year-old at the dinner table: She may be clever, she may even be right, but her constant need to interject herself impedes the conversation’s progress.

And that may be the book’s biggest flaw: Wurtzel is annoying. In spite of her astounding mastery of history and her unwillingness to shrink from the truth about where feminism has left women, her voice sounds too young and unseasoned to trust. Even the litany of her naughty escapades–screwing an Italian tattoo artist, snorting heroin, screwing a man twice her age, snorting coke–smacks of smugness, not depth and wealth of experience and sorrow of the sort that makes people speak quietly and honestly.

In the final chapter she lets slip a glimmer of humanitarianism: “And [forgiveness over vengeance] has to be the guiding principle, it is the only chance any of us has for happiness.” But that’s a half page from the end, and the rest of that chapter is Wurtzel dissolving into despair that she’ll be old and unmarried, or else explaining how that would be fine with her–she says both–and so ultimately the forgiveness schtick just seems like so much theater.

Once disciplined and experienced, Wurtzel will be amazing. Until then, readers will need patience and occasionally the help of a good dictionary.

From the June 18-24, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.