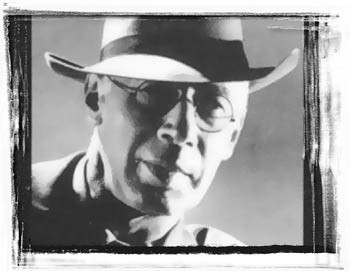

Miller Time

Recalling the genius of an American colossus

By Stephen Kessler

HARD to believe it’s been 20 years since Henry Miller left us. AT 88, Miller lived out the final days of his extraordinary life in a big colonial house in Pacific Palisades, an unlikely last stop for his odyssey.

He had started out on the streets of Brooklyn at the end of the 19th century, attempted unsuccessfully to “come of age” in New York City, escaped to the lower depths of subbohemian Paris, where he belatedly found his voice as a writer and wrote his first three monumental books, left Paris for Greece on the eve of World War II, returned to the States and traveled the country discovering why he’d fled in the first place, and eventually settled for several years like some kind of Chinese sage on a ridge above the Big Sur coast.

The rigors of living so far from civilization in his advancing years, combined with the royalties from international sales of his many books, conspired to take him to the L.A. suburb where, by now a self-made legend, he enjoyed the luxuries of commercial success and disappeared into the sunset.

In the early 1990s, scholars Mary Dearborn and Robert Ferguson published new biographies of Miller, novelist Erica Jong brought out a book-length personal appreciation, and Philip Kaufman’s film Henry & June, based on the journals of Anaïs Nin, temporarily reminded us of the writer’s special place in the century’s literary landscape.

But since then he’s pretty much vanished from the cultural radar.

This is especially ironic in light of the rise of the personal memoir as one of the most popular literary forms and the recent apotheosis of Jack Kerouac as the great American rebel automythographer.

It’s hard to imagine either Kerouac or the memoir emerging as major forces in U.S. publishing without the precedent of Miller’s free-form taboo-smashing example.

Miller’s first book, Tropic of Cancer, written in the author’s early 40s and published in Paris in 1934 (but banned in this country until 1961 on account of its alleged “obscenity”), begins with a prophetic epigraph from that most American of writers, Ralph Waldo Emerson: “These novels will give way, by and by, to diaries or autobiographies–captivating books, if only a man knew how to choose among what he calls his experiences that which is really his experience, and how to record truth truly.”

Miller, even now, maintains his scandalous reputation, known by most as a writer of “dirty books.”

But those who actually read his work in all its remarkable variousness may come to understand that, while he is a ribald and outrageous storyteller, he is also, like Emerson, a philosopher.

Tropic of Cancer is a shocking book not just for its frankly sexual and scatological aspects but for its fearless confrontation with a civilization collapsing in a spasm of spectacular decadence.

Just a few years before Hitler sends Europe into a cataclysmic war, Miller discerns, in the squalor of his immediate circle of degenerate friends and acquaintances, the symptoms of a more pervasive ailment, a moral cancer that he sets out to expose, sparing no one, least of all himself.

That he is able to tell this degraded tale in a prose that, for all its darkness, is nothing less than exuberant, is some kind of miracle.

Imagine Spengler’s The Decline of the West, Eliot’s The Waste Land, Sartre’s No Exit , and Dylan’s “Desolation Row” combined and retold by the mutant manic offspring of Mae West and Groucho Marx, and you have some idea of the apocalyptic energy of Miller’s breakthrough book.

Obscene, perhaps, but only as a frighteningly and hilariously honest depiction of a world that’s all too real.

In Tropic of Cancer, Miller attempts to hasten the razing of this corrupt world while at the same time eradicating his personal catastrophe, which includes up to then not only his abject failure to accomplish anything in 40 years of earthly existence but also his tormented erotic obsession–sometimes known as love–with the woman who was to be his lifelong muse and goad and inspiration, his second wife, June (aka Mona).

The impoverished, directionless, hopeless yet comical account Miller’s autobiographical narrator records could easily be considered nihilistic, but it’s Miller’s lyric genius, in the transcendental spirit of Emerson, to lift his sordid material from the depths of its own depravity into something resembling redemption.

Toward the end of this harrowing sustained exercise in creative rage, the author contemplates the crotch of a prostitute and launches into one of the most memorable riffs in literature, a 10-page diatribe against “a world tottering and crumbling, a world used up and polished like a leper’s skull,” a world that breeds, alongside the human race, “another race of beings, the inhuman ones, the race of artists who, goaded by unknown impulses, take the lifeless mass of humanity and by the fever and ferment with which they imbue it turn this soggy dough into bread and the bread into wine and the wine into song.”

Miller aligns himself with this race of artistic monsters and declares, in a paroxysm of exasperation that amounts to a manifesto, “A man who belongs to this race must stand up on a high place with gibberish in his mouth and rip out his entrails. . . . And anything that falls short of this frightening spectacle, anything less shuddering, less terrifying, less mad, less intoxicated, less contaminating, is not art.”

This is a high standard for any artist to set for himself, but Miller at his most possessed and most inspired meets it, in this and many of the later books.

From the portrayal of his lowdown immediate surroundings in Tropic of Cancer, Miller turns a backward glance on his young manhood in New York in the equally scandalous and even funnier Tropic of Capricorn, whose first 100 pages relate his years of employment with the Cosmodemonic Telegraph Co., one of the most engrossing portraits of corporate bureaucracy ever consigned to paper.

But Capricorn, as its goatish title suggests, is mostly about its horny narrator’s unquenchable thirst for sex and his simultaneous search for meaning in a world that seems no more nor less than maddeningly chaotic.

More coherent as a narrative than Cancer, despite its many digressions and lack of a conventional “plot,” Tropic of Capricorn is Miller’s portrait of the artist as a young man who can’t quite figure out how to be an artist.

Despite his anguish and confusion and pain and despair, the antiheroic protagonist’s story is once again told in such joyfully charged prose that it practically lifts you out of your seat as you read.

This guy may be hurting, but he’s alive in a way that you can only hope to be–not necessarily by indulging your every forbidden appetite but by paying such close attention to your difficulties and to the details of your oppressive environment that even your failures become something to celebrate and thereby turn into evidence of an undefeated existence.

In the third and final book of this initial trilogy, Black Spring, Miller abandons the novelistic pretense of telling any single story and instead creates a kind of collage of sketches, portraits, vignettes, essays, and poems-in-prose that once again combine to reveal the author in all his prodigious originality.

This is the book, if the uninitiated reader can suspend the desire for conventional narrative and surrender to the spell of Miller’s voice, that may be the best one-volume introduction to the author’s work, as it represents multiple aspects of his literary persona.

Perhaps the most marvelously disorienting section of Black Spring is “Into the Night Life . . . A Coney Island of the Mind,” a 30-page dreamlike prose fantasia whose wild inventiveness, richness of imagination, and gorgeous sentences are breathtaking.

Here is Miller cut loose beyond the stench of rotten circumstance and the arbitrary limits of “making sense” into a realm of ecstatic revelation, the writer as clown working the high wire without a net, performing for nothing so much as his own delight.

The joy with which this acrobatic prose is infused is dangerously contagious. I say dangerous because, attempted with less virtuosity, this kind of writing, liberating as it may feel, is likely to result in an utterly unreadable mess.

But why not, Miller might answer, make a mess? Life itself is a mess, and isn’t art obliged to be faithful to life? Miller was also an accomplished amateur watercolorist, a selection of whose pictures appeared after his death in a book appropriately titled Paint as You Like and Die Happy.

His writing–from the Tropics and Black Spring through the wonderful books of essays (The Air-conditioned Nightmare, Remember to Remember, Stand Still Like the Hummingbird, The Cosmological Eye, and others) and the great book on his stay in Greece, The Colossus of Maroussi, to the excruciating Rosy Crucifixion trilogy (Sexus, Plexus, and Nexus, the epic saga of his life with June)–is radical testimony to the artist’s freedom to ignore existing rules and do it however he or she feels moved to make a singular statement.

Not everyone can get away with such defiance of propriety. Even Miller, at his worst, can be tiresome and sloppy. And not everyone has the nerve or courage or madness or whatever it takes to risk colossal failure by taking such a path.

But his friend Lawrence Durrell, describing Miller as “one of those towering anomalies, like Melville or Whitman,” places him in his proper context among the giants of American literature, a source of consternation to some, consolation to others, and inspiration to those who would find a form and style of expression true to their own experience.

From the November 23-29, 2000 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.